A Tool of Queerness? Queerness and the DALN

DEBORAH KUZAWA

ABSTRACT

What might queerness—as an epistemological and ontological concept untethered from sexuality and gender—and the DALN offer to the discipline of composition studies? I contend that the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives is both a queer and queering archive for classrooms and research. The underlying structures and implicit values of the DALN are queer in that they simultaneously push against and embrace dominant binary values that shape archives, archival research, and literacy. The DALN’s structure and values surf between the values, structures, and conceptions of conventional archives and Archives 2.0 (technologically-enhanced archives), embracing a queer middle ground that values movement and both/and. Instructors and students may use the DALN to better understand conventional binary values of archives (restriction/openness, impersonalness/personalness, expert-direction/self-direction) and how they manifest in archival spaces, classrooms, and research. These binary values normalize and privilege particular configurations of archives and classrooms, including when, where, and how archives and the personal appear (or don’t) in composition classrooms and research. The DALN may be used to expand understandings of what archives and literacy can be, what archives and literacy look like, how archives and literacy are used, and who/what are preserved in archives or who is considered an expert. I argue the DALN may be used in classrooms to meet practical and institutional goals for composition courses as well as meet the personal, philosophical, and intellectual goals of instructors, students, and researchers.

***

Archives have the power to privilege and to marginalize. They can be a tool of hegemony; they can be a tool of resistance. They both reflect and constitute power relations. —Terry Cook and Joan M. Schwartz (2002)

Queer archival practices… are nontraditional, anti-institutional, and ephemeral. They challenge basic understandings of what counts as evidence and where and how… experiences can be represented. —KJ Rawson (2012)

Archives are not just repositories but complex histories of

activities, cultures, memories, and sociocultural values. When archives 1

is used to identify a collection such as the Digital Archive of

Literacy Narratives (DALN), the term’s baggage impacts how that

collection is understood. The DALN is a typical archives in that it

is a complex repository of histories and values, but I contend it is

an unusual and queer/ing archive: it preserves

first-person stories of everyday people who may contribute

independently of DALN representatives, and contributors determine

what literacy means and looks like and what topics will be covered.

As Rawson (2012) argues, queer archives “challenge basic

understandings of what counts as evidence and where and how…

experience can be represented” (p. 239), and I argue that this

quality makes queer archives especially fruitful for classroom use.

Students and instructors alike can engage with DALN as researchers,

curators, and subjects, honing and circulating their own literacy

expertise through engagement with the DALN. Unlike most archives,

the DALN allows ordinary people to take control of their archival

experience and become part of the history and legacy of literacy.

I argue that the DALN is an example of 21st-Century, queer archives because it embraces an oscillating path that reflects our complex, multiplicitous, and self-directed technological moment. The DALN surfs between the values, structures, and conceptions of conventional archives and Archives 2.0 (technologically-enhanced archives), embracing the queer middle ground that values both/and. As Comer and Harker (2015) note, “the DALN is shaped by tensions” that “resist easy access,” and I argue that these tensions are how the DALN navigates and moves between the binary values that surround archives (and literacy). This movement and these tensions can make it difficult to engage with the DALN, but they are central to the DALN’s queerness and its malleability as a resource.

Further, the usefulness of the DALN’s position as an queer archive reflects the archival turn in composition studies more broadly. Within composition studies, the “archival turn” in the field is generally traced to the May 1999 issue of College English, which was dedicated to archives and archival research (see Comer & Harker, 2015; Gaillet, 2012; Ramsey, Sharer, L’Eplattenier, & Mastrangelo, 2010). In general, the archival turn has concentrated on preserving, reimagining, and adding to the histories of the field as well as looking to spaces outside of the field for inspiration and insight into composition, its histories, and its praxis. The DALN, although not developed until nine years after the College English issue, could be considered part of the archival turn in the field because composition scholars have been a driving force in its development.

However, for the most part, this archival turn has not made

archives themselves the subject of the scholarship but instead has

focused on archives’ contents. My goal here, and my contribution to

composition’s archival turn, is to examine archives qua

archives as a way to better understand their underlying values. In

particular, I am interested in how the DALN, as a public archive of

composition and literacy studies, might help us understand

queer values and the possibilities of queerness for classrooms and

pedagogy. My goal is to take a queer view of archives,

literacy studies, and pedagogy as a way to open up the possibilities

for literacy narratives, archival research, and composition

classrooms, expanding established knowledge and creating new

knowledge.

The DALN fits into the conversations (and conventions) about personal narratives and archives already present in composition studies and archival studies but also pushes against those conversations (and conventions), helping demonstrate its position as queer/ing archive. The DALN provides a space for scholars, teachers, students, and others to not only research literacy practices and values but also create and circulate literacy-focused personal narratives and knowledges specifically for an archive. In the process, ordinary people shape the knowledges and stories of literacy and the role and goals of archives.

In this chapter, I explore the dominant values underlying archives in order to better understand how the DALN might function as a “queer influence… [to foster] new ways of thinking about the archive, including new practices of research and exhibition” (Cvetkovich, 2012), in archival spaces broadly and within composition studies and composition classrooms more narrowly. Queerness (and queer values), according Sedgwick, lives in the “open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning” (1994, p. 8). Understanding the values that underlie archives reveals not only the realities of archives (both in general and in particular) but also how they might be a “tool of resistance” and/or a “tool of hegemony” (Cook & Schwartz, 2002). Particularly important for this project is how archives such as the DALN might be a tool of and for queerness, and I use this chapter to ask what it might mean and look like if we consider the DALN to be a tool of/for queerness in college classrooms and writing pedagogy.

This chapter unfolds in two major waves: analysis of archival structures and values, including queer archives, and discussion of how the DALN fits/doesn’t fit within that category, followed by exploration of how the DALN might be useful and productive for the work of writing classrooms, based on instructor feedback gathered in an open-ended questionnaire. Thoughout, this study evaluates the foundational values of archives that shape everyday archival structures, realities, and expectations, and how archives and their values appear in our classrooms.

The DALN and Me: A brief and queer personal literacy narrative

|

Thinking about structures and values: What are archives and their values?

At the heart of this project is definitional and metaphorical understanding: what are the values of archives, and how might those impact how the ways we research in and about, engage with, and teach about and with archives (including the DALN) in our classrooms? When does something become archives or archival research, and when is it something else? Who decides what is or is not an archives, and what is the definition being used to measure whether something qualifies as an archives? And ultimately, does it even matter?

I argue that this all matters because archives are powerful; they provide evidence of events, perspectives, lives, and connections. Archives are a feedback loop of power: they preserve certain stories and materials and in that process, grant power to the knowledge and truths in the materials—and the preservation of the knowledge and truth claims justifies their power. Definitions of archives and archival work (and underlying values) constitute the limits of what we can imagine for archives in composition scholarship and classrooms. I argue that the DALN helps push those limits beyond conventional understandings and values.

Implicit values are central to understanding how different types of archives exist, function, and reinforce a range of values and beliefs about archives, their purposes, and their contents. Values are mapped onto everyday structures, from the physical (e.g., buildings) to virtual (e.g.. computer interfaces), and these values are most often implicit (Hunter, 1997). This is true for archives, where discourses and structures are seeped in binaristic values, reflecting (both overtly and tacitly) the perspectives and values of those who maintain and control archives. Skinnell (2010) argues, “the structure of the archive…determines what can be archived, and therefore the rhetorical uses to which the contents may be put.” Archival structures reveal archives’ implicit values—even if those engaging with (or designing) the interface do not “acknowledge or support” such a position (Selfe & Selfe, 1994, p. 481)—including processes of access and use, contribution and accession, and audience and location. Structure impacts what or who can be part of archives, who can access archives, and what can be and what is done with archives and their records.

Exploring the implicit values of conventional and 2.0 archives provides us a way of understanding how the DALN queers those values and structures. To talk about the structure of archives (or most anything else created by humans) is to talk about the values (and attendant binaries) that serve as the foundation for archives. Exploring and exploiting archival structures, particularly the DALN’s structure and attendant values vis-à-vis conventional archives and values, are ways to (re)consider the role that archives and their knowledges may play in writing classrooms and research.

The Society of American Archivists and archival values

Talking about archives and their values means engaging with The Society of American Archivists (SAA), which establishes the central values and code ethics for archival professionals in the United States. Though most in composition may not have read the SAA’s documents, we still feel their impacts when we research and teach in and about archives. The SAA provides two documents to establish the field’s values: “Core Values of Archivists” (Society of American Archivists Council, 2011) and “A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology” (Pearce-Moses, 2005a). The glossary establishes the values of the SAA by providing definitions or delineations of different terms, including archives. When examined together, these documents provide a more complete understanding of the values central to and shaping the archival profession in the U.S.

“Core Values” stresses the social responsibility of archives and archivists, including “the widest possible accessibility of materials,” by promoting the use of materials through public policy and advocating for the preservation of diverse materials for a range of communities (Society of American Archivists Council, 2011). Despite the seeming openness of the “Core Values” document, the SAA’s definition of archives rests upon expert-direction and restriction. Archival experts (i.e., trained archivists and occasionally librarians) determine what records to preserve and how to describe those records, which are then stored in a particular, often restricted, building or area of a building. The purpose of conventional archives is to maintain materials “as evidence of the functions and responsibilities of their creator, especially those materials maintained using the principles of provenance, original order, and collective control” (Pearce-Moses, 2005a). Unspoken here are the specific values that such judgments are based on. Who, exactly, is making the judgment of value or usefulness, using what standards, for what communities or groups?

Archives, like history itself, have been controlled by the victors, by those in power, and often to the detriment of less powerful groups because, according to Cook (2000), “Archives traditionally were founded by the state, to serve the state, as part of the state’s hierarchical structure and organizational culture” (p. 18). Although implicit, these behind-the-scenes, expert-driven judgments impact the values, contents, access, and goals of archives and archival practices. As I detail below, these values are evident through examinations of archival structures. If we are working with archives in our classrooms, we must explicitly name and explore the values and norms archives rest upon.

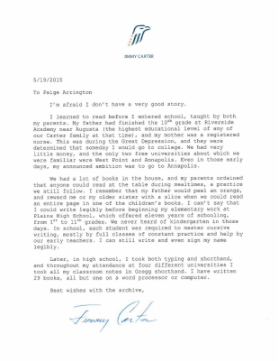

“I don’t have a very good story”: Downplaying our literacy stories

|

Conventional Archives, Archives 2.0, and Values

Evolutions in technology and social and cultural norms have meant emphasis on different aspects and values of archives, but much of the literature in library and archival studies and in composition studies still tends to position archives and archival materials—including Archives 2.0—in conventional ways (Theimer, 2009, 2011; cf. Burton, 2005; Donahue & Moon, 2007; Kirsch & Rohan, 2008; Ramsey, Sharer, L’Eplattenier, & Mastrangelo, 2010). Conventional archives’ content and structures are generally shaped by gatekeepers: libraries and librarians; professional archivists and professional archival organizations; and institutional representatives and institutional goals, mission, and values.

Cook and Schwartz (2002) argue, “Archives validate our experiences, our perceptions, our narratives, our stories… Users of archives (historians and others) and shapers of archives (records creators, records managers, and archivists) add layers of meaning, layers which become naturalized, internalized, and unquestioned” (emphasis added, p. 18). Cook and Schwartz’s categorization of users focuses on expert gatekeepers (historians and researchers) who interpret materials for a larger and often more public audience and demonstrate that expert vetting of people, materials, and access is central to archives, determining the who, what, when, and how of archives’ contents, access, and use. In other words, within conventional practices and studies, archives are about restriction, experts, and expertise.

***

As noted earlier, the archival turn in composition is generally understood as beginning with the May 1999 issue of College English. More recent work from the past decade can help us understand composition’s general conception of archives, which is quite similar to archival studies’: Local Histories, 2007; Beyond the Archives: Research as a Lived Process, 2008; Working in the archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition, 2010; and College Composition and Communication’s September 2012 special issue on “Research Methodologies.” For the most part, composition’s archival concern has been uncovering and emphasizing forgotten or buried experts and histories of composition studies as a way to shift understandings of the field’s foundations and growth (Donahue & Moon, 2007; Kirsch & Rohan, 2008; Ramsey, Sharer, L’Eplattenier, & Mastrangelo, 2010). These edited collections and the special issue provide insight into the complexities of archival work being done by rhetoric and composition scholars, but at the same time, archives themselves are positioned as relatively stable and straightforward. The purpose of the collections and special issue (like the purpose of much archival-focused scholarship in composition and elsewhere) is not to define and explore archives as archives but to explore how they fit into the established research methodologies of the field and provide evidence and inspiration for research. In the process, archives (and their values) are indirectly defined and that definition is based on the values and structures that originate in archival studies, leaving the primary values of conventional archives originating in archival studies in tact.

Following work in composition studies, the SAA, and Cook and Schwartz (2002), I argue that the primary values of conventional archives (and including many Archives 2.0) are restriction, impersonalness, and expert-direction. These values exist in an often unspoken binary tension with their (perceived) opposites (see Table 1).

| Restriction | Openness |

| Impersonalness | Personalness |

| Expert-direction | Self-direction |

Table 2: Values in Conventional Archives*

Values=Gray; Structures=Green

| Restriction |

Impersonalness |

Expert-direction |

|

| Access/Use |

|

|

|

| Contribution/Access |

|

|

|

| Audience/Location |

|

|

|

- *Examples: The National Archives; The Byrd Polar Research Center Archival Program; The Ohio State University Archives. See: Jenkinson, 1937; Schellenberg, 2003; Society of American Archivists; Stapleton, 1983

Archives 2.0

So what of archives that are available online? Discussing modern archives means engaging with a variety of technological changes and issues, such as born-digital content and Web 2.0 resources and functions such as social media, cloud computing and storage (Evans, 2007; Monks-Leeson, 2011; Nelson et al., 2012; Theimer, 2011). Archives 2.0 are commonly theorized as conventional archives-plus-Web 2.0—that is, online archives containing digital surrogates of physical archival materials, sometimes with Web 2.0 usability such as commenting, saving materials into a favorites list, and so on (Manoff, 2004; Monks-Leeson, 2011; Theimer, 2011).

In common practice, most Archives 2.0 are the digital presence of physical archives, such as online components of the Smithsonian Institution Archives and the U.S. National Archives, where nearly all of the online records are digitized surrogates of physical items held in relatively restricted buildings. Other examples of Archives 2.0 include Ancestry.com, ONE Archives, and QZAP: Queer ‘Zine Archive Project, which contain digital surrogates with occasional born-digital content and a range of interactive Web 2.0 features. Ultimately this means that most Archives 2.0 rely on the values of conventional archives, maintaining similar structures and processes (see Table 3).

Values=Gray; Structures=Green

| Restriction/ Openness |

Impersonalness/Personalness |

Expert-direction |

|

| Access/Use |

|

|

|

| Contribution/Access |

|

|

|

| Audience/Location |

|

|

|

- * Ex: Ancestry.com, QZAP: Queer ‘Zine Archive Project; Mass

Observation Archive; ONE Archives; See: Eichhorn, 2008; Hui,

2013; Monks-Leeson, 2011; Theimer, 2009, 2011. Although popular

collections such as YouTube may be used as archives by some

users and groups, it is not necessarily an archives (i.e. it is

not used for historical preservation or items of enduring value

but rather as a type of cloud storage). Unlike most collections

considered Archives 2.0 in the archival world, one may delete

contributions and remove one’s account from YouTube whereas

Archives 2.0, like conventional archives, are focused on

long-term preservation and do not allow items to be removed.

Conventional archival structures and practices tend to be on the left side of the value binaries, privileging restriction, impersonalness, and expert-direction. Archives 2.0’s values alternate somewhat between the restriction/openness and impersonalness/personalness because their digital existence means that there is inherently a larger degree of openness and personalness to access/use, contribution/access, and audience/location. At the same time, though, experts play a major role in determining what and who are excluded and included in archives and what will be widely available.

***

At a basic level, the DALN defies standard archival theories, practices, and values because the contents of the DALN are not natural accumulations of organizational or institutional records, as archival scholars and theorists describe archives’ contents (Hunter, 1997; Jenkinson, 1937; Schellenberg, 2003). Hunter (1997) claims, “Archival materials… are never explicitly created—no one in an institution says, ‘Today I think I’ll create some archival records.’ Archives grow organically as part of the creation of record in the normal course of an institution’s business” (p. 8). When narrators share a narrative with DALN, they are deciding to “create some archival records.” Individuals consciously create media for archival storage/retrieval, and these records are individually authored (though occasionally multi-authored), personal stories rather than records of institutional workings.

Further, unlike conventional and archives 2.0, the focus of stories is self-determined within the large category of literacy as defined by the narrators as are the metadata (i.e., finding aids). The purposefulness and personalness—the knowledge that what one is creating is intended for an archives and is based one’s own personal experiences—defies both conventional and Archives 2.0 values and practices. These practices and values align with queer understandings of archives as noted by Cvetkovich (2012) and others, such as contributors to Make Your Own History, edited by Bly and Wooten (2012), who argue that queer archives rely on a valuing and conscious preservation of ideas, experiences, and knowledges. The following section explores queer archives and their values as they relate to the DALN.

Preserving queer/ing stories

|

Queer archives and the DALN

Part of my process and purpose of examining the DALN is to explore how the it functions as a queer archive and therefore how the DALN might help us understand and envision queerness as a set of (malleable) values that may provide a different or differently nuanced understanding of the world, including classrooms. Whereas conventional and Archives 2.0 tend to fall on one side of the binary values noted in Figures 2 and 3, queer archives (including the DALN) move between restriction and openness, between impersonalness and personalness, and between self-direction and expert-direction, demonstrating that binary values are not either/or but exist on a continuum.

Tom Boellstorff (2010) argues that it is impossible to exist outside of binaries completely because we live in a culture seeped in them, but at the same time, no binaries determine our values unilaterally. He claims surfing binaries as “a queer method could recognize the emic social efficacy and heuristic power of binarisms without thereby ontologizing them into ahistoric, omnipresent Prime Movers of the social” (2010, p. 223). Our values are not determined solely by any binary extreme, and surfing binaries recognizes meaning in the movement between oppositional ideas and values rather than taking one side or the other.

In terms of its structures and values, the DALN moves between restriction and openness, between impersonalness and personalness, and between self-direction and expert-direction, demonstrating that binary values are not either/or but exist on a continuum. I argue that this movement reflects lived reality, and as such, the DALN provides a model and a space for exploring how we might surf dominant binaires and values of not only archives but also classrooms and the world more broadly. The Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives raises questions of:

- what archives and literacy are, look like, and how they function,

- who can access and contribute to archives,

- what is appropriate for archival preservation and storage, and

- how we might incorporate archives and archival- and literacy-based research into our classrooms.

Similar to composition scholarship involving archives, scholarship about queer archives tends to focus on the contents and their uses in classrooms and research rather than the archives themselves (see Table 4). Generally, queer archives are conceptualized as archives containing records of LGBTQ lives and LGBTQ cultural productions, with little attention to what it might mean to conceptualize archives that are not exclusively about LGBTQ lives as queer (cf. Archivaria #68, 2009; Cvetkovich, 2003, 2012; Halberstam, 2005; Rhodes & Alexander, 2012). I ask: What are the possibilities that queer values in archives might provide? and What are queer ways of structuring, preserving, accessing, and contributing to archives and “surfing the binaries” of archives and beyond?

Values=Gray; Structures=Green

| Restriction ⇳ Openness |

Impersonalness ⇳ Personalness |

Expert-direction ⇳ Self-direction |

|

| Access/Use |

|

|

|

| Contribution/Access |

|

|

|

| Audience/Location |

|

|

|

- * Ex: DALN; Occupy Archive; Lesbian Herstory Archives; Grassroots Feminism.net; ComFest Archives. See: Danbolt, 2005; Halberstam, 2005; Cvetkovich, 2003, 2012

When we turn to queer values as a way to understand and interact with archives (particularly the DALN) in our classrooms and research, we can help to disrupt not only our own pedagogies and students’ understandings of archives and archival research but also broader understandings of what it means to engage with and research in and about archives. Perhaps more importantly, we can disrupt the signifier/signified relationship of queerness, demonstrating how queerness is more about values and worldview rather than limited to sexuality and gender.

Queer archival values are about re-imagining the values of archives and what manifestations of those values might look like. Viewing queerness in terms of values helps demonstrate how queerness is not only about sexuality or gender but also about the ways we view and engage with the broader world. Queerness thrives in space of disruption, or the spaces and movement between conventional, official (and powerful) concepts and understandings of the world and alternative, often oppositional understandings (Harper, White & Cerullo, 1990; Renn, 2010; Warner, 1993). Shifting between binaristic values demonstrates that each side, each extreme, is implicated in the other. Further, by exploring queerness as a set of values we disrupt the notion that queerness is only about sexuality or gender and therefore valuable only for certain communities.

Though scholars who engage with queer archives, such as Ann Cvetkovich and J. Jack Halberstam, tend to focus on archives about and for queer people and their cultural productions, Cvetkovich (2012) provides a set of questions for re-examining what is worthy of archives, what should count as archival material, where archives exist, and how they are accessible. In the process of asking these questions, Cvetkovich provides a framework for understanding queer archives as a set of values and an aesthetic rather than only a sexual or personal identity. Cvetkovich (2012) asks:

[W]hat kind of archive [do] we want: a traditional archive with paper documents and records, or one that uses ephemera to challenge what we mean by archive? Inclusion and assimilation into existing archives, or a separate (but equal) archive? Or do we want an entirely different version of an archive, one that perhaps lies outside a bounded spatial enclave? What (and where) is the queer archive? (original emphasis)

In many ways, Cvetkovich’s questions are philosophical and ontological. I believe the questions she poses can be used to push against conventional understandings of archives and composition, literacy, and classrooms. Further, she argues that queer archives and queer archival projects “produce new and unpredictable forms of knowledge including new understandings of what counts as an archive and hence what counts as knowledge” (Cvetkovich, 2012). I argue that the DALN’s structure encourages unpredictable contents, partly due to the self-direction required to contribute and openness and self-definition of literacy. As a result, projects involving the DALN may provide different perspectives on literacy, expertise, identities, research, and archives.

Cvetkovich also provides three tenets that queer archives often rely upon. These tenets correspond to the binary archival values discussed throughout this chapter:

- creative understandings of subject matter and genre, including the genre of the archive [openness];

- emotional connections and expressions [personalness and self-direction]; and

- a degree of visibility and invisibility [openness/restriction; self-direction/expert-direction]. (Cvetkovich, 2012)

Although Cvetkovich is concerned with archives produced or curated by LGBTQ people, the tenets she highlights revolve around the binary values that shape archival discourse, regardless of whether queer people/productions are the focus of the archives. The DALN’s refusal to provide a singular definition of literacy and acceptance of a broad conceptualization of literacy goes against the academic grain and is evidence of how the DALN’s queer structure can lead to queer contents.

For example, the DALN narrative “From a Drag King to Just a King” (2010) by Adam Apple focuses on his experiences as a drag king performer and his transition as a female-to-male transgender person (see Figure 2 for a screenshot).

In some ways Apple’s narrative, like Singleton’s 2010 and 2015 narratives, could be considered more of an autobiographical sketch tracing his transgender identity than a personal literacy narrative. (Other examples of narratives that may seem to be more life, community, or family narratives than personal literacy narratives include Shingledecker, 2012; Martin, 2011; Potts, 2013; there are an untold number of narratives that weave personal and family histories and literacy experiences and provide insight into far more than an individual’s literacy practices.) However, his narrative is all about language and learning—how to read gender and identity as inherently multiple and complex in a society that is based on binaristic notions (and language) about gender and identity. In this way, Apple’s narrative is a literacy narrative because it is about reading the body and reading the world. If the DALN restricted narratives to only those that explicitly discussed reading and writing alphabetic text, Apple’s narrative (and Sile Singleton’s and dozens if not hundreds of other narratives) might be excluded because it is based on a queerer understanding of what literacy is and looks like. Letting the concept of “literacy narrative” be self-determined on a personal basis permits an open interpretation of the genre. As stories meant for an archives, self-direction also means openness in understanding the purpose and genre of archives. Additionally, self-directed and personal interpretations of literacy, literacy narratives, and what is appropriate for an archive impact the social meaning of literacy and archives as the narratives circulate in spaces outside of the DALN.

Queer archives beyond sexuality and gender

Some examples of queer archives that are not primarily about LGBTQ people and productions include the ComFest Museum and Archive (see Figure 3, a screenshot of museum/archive website), which does not have a digital presence, is available one weekend per year, encourages people to contribute, and allows viewers to touch and interact with materials, most of which is ephemera; and GrassrootsFeminism.net (see Figure 4, a screenshot of the site’s digital archive), a site dedicated to growing a global feminist community and preserving relevant materials (as determined by the users of the site). Both of these examples are not primarily about queer people and their cultural productions, but they are queer due to their structures and values, which alternate between restriction/openness and expert-direction/self-direction.

At its core, the DALN, like the ComFest Archives and Grassroots Feminisms Archives, is a queer archive because its structures and values both embrace and resist the structures and values of conventional and 2.0 archives. I argue that one of the largest tensions—and a barrier to easy access—in the DALN is between visibility (openness) and invisibility (restriction). What or who is visible or invisible, allowed or barred access, and what values are invisible or visible in the DALN as a whole and within individual narratives? Unlike other archives, the tension between visibility and invisibility in the DALN does not rest solely on expert, curatorial decisions or a lack of space (see Davy, 2008).2 The openness of the structure and materials, such as the demographic information form that contributors complete, is a central source of the restriction/openness tension in the DALN (see the DALN website for a copy of the demographic and keyword form); contributors choose which information to provide (or not provide) and provide whatever terms they would like to use to identify themselves and their contribution, from demographic information to keywords.

The open-ended, self-determined forms and self-archiving nature of the DALN can be a major frustration for users, especially academics and those performing research, because there is no consistency in terms or the amount of data provided with each narrative. This may also dissuade instructors from using the DALN in the classroom. However, the reality is that archival research is always already difficult. Lawrence Stone claims, “Archival research is a special case of the general messiness of life” (as cited in Blouin & Rosenberg, 2011, p. 132). In other words, archival research is messy regardless of the type of archive because lives are messy. I contend that in the case of the DALN, this messiness is more evident due to its overall openness and self-direction. Unlike most archives, the DALN puts its messiness on display.

Instead of becoming frustrated by the limitations of the DALN, instructors can use it as a starting point to perform rhetorical analyses of archives as archives (including a discussion of research methodologies and expectations in different contexts), power/authority, and the ways in which power, structures, and practices of archives (and classrooms) reveal implicit values and the ways those values play out. Ulman (2012, 2013b) emphasizes again and again that in order for the DALN to be successful (i.e., engaging contributors and users from a range of backgrounds), the process for contributing must be as simple and straightforward as possible, and this places emphasis on the self-direction of contributors: what terms and which stories will make sense for their participation in the project?

As a result of this self-direction, some narratives are virtually hidden because they do not have much or any searchable data such as keywords and demographic information. For example, at the 2010 TransOhio Transgender and Ally Symposium, a woman recorded a narrative with explicit instructions that she did not want any information (such as demographic information, the symposium name or keywords) other than her name attached to her narrative. This means that unless one knows the contributor’s name or the date on which she contributed her narrative, the narrative is practically impossible to find. A user likely would have to know beforehand that the narrative exists in order to do this type of search. However, even if so-called hidden narratives in the DALN are difficult to find, they are not completely impossible to find.

A queer value system recognizes that the play between visibility and invisibility can be important for survival, community, and knowledge production, even if these are not visible or understood by viewers or users. This particular contributor decided to tell her story and place it into a public space, even if no or few people hear it, because it serves a personal, undisclosed purpose. Any DALN contribution, including those that are tagged and have attached demographic information, may never be listened to, just as the records of many archives are never viewed after they are archived. The distinction for the above-mentioned narrator is her personal and conscious choice to limit the visibility of her narrative.

Surfing the binaries

|

The DALN: A queer archives, queer pedagogies for composition classrooms

Comer and Harker (2015) suggest that “the DALN, in itself, offers a fascinating artifact for study.” In part, that has been my goal with this project: to make the DALN itself, as an archives (rather than only its contents), an object of study, with the goal of understanding how its structure and underlying values might impact how some instructors, students, and others understand and engage with the DALN, archives, and literacy narratives as well as what counts as research into literacy.

In addition to examining the DALN through the lens of archives, archival studies, and queer studies, I distributed an open-ended survey to small selection of college compositions instructors (n=9) from around the country who use the DALN in their classrooms. The questionnaire asks specific demographic questions and questions about personal narratives and other literacy resources vis-à-vis the DALN. I believe this type of contextualization may provide a nuanced perspective of the DALN-in-context as well as encourage questionnaire participants to think about the DALN as a resource in and of itself, rather than thinking about only its contents.

My questionnaire consisted of all open-ended questions because I sought to mimic the experience of filling out the DALN paperwork, which contains only open-ended questions. I also used open-ended questions because they generally produce narrative responses, which, according to Reja, Manfreda, Hlebec, & Vehovar (2003) can provide “a much more diversified set of answers…. [and] the possibility of discovering responses that individuals give spontaneously, and thus avoiding the bias that may result from suggesting responses” (p. 166, p.163). Though open-ended questions can result in a lot of (messy) data, the data may provide nuanced insights that could not be anticipated by those administering a questionnaire.

The results of the questionnaire, though not generalizable to all composition classrooms and instructors, suggest that the DALN provides a space for students and instructors to (queerly) explore, define, research, and ultimately surf the binary concepts and values related to literacy, scholarship, and research. Questionnaire responses confirm my own experiences: the DALN lends itself to queer pedagogies because of its implicit values and explicit structures for contribution and access.

Queer pedagogies

Queer pedagogies focus on exploiting normalizing binaries, many of which are implicit and/or invisible in our day-to-day lives, and this requires reflection and meta-analysis. Shlasko (2005) argues that one of the goals of queer pedagogies is to “critically examine processes of normalization and reproductions of power relationships, and complicate understandings of binary categories” (p. 125). Contextualized, critical reflection by instructors and students is required in order for queer pedagogy to be effective. In working with the DALN, this may manifest in explicit discussions about dominant discourses, values, and the various binaries that shape traditional classroom spaces and dynamics, including our own.

However, examining dominant binaries and power hierarchies is not enough; Luhmann (1998) argues that “a queer pedagogy must learn to be self-reflective of its own limitations” as well (p. 121). For different classrooms and instructors, the limitations will be different—from students invested in dominant power hierarchies, values, and binaries (and therefore resistant to critiquing binaries), to university/employer restrictions on course content and outcomes, to basic resistance to the word queer regardless of how it is defined or discussed. In other words, though I argue that the DALN is a queer resource and well suited to queer pedagogies, I recognize that others may not not view it in this way or may not be able to articulate or utilize the DALN’s queerness due to contextual restraints.

The Challenges of Queer Pedagogies

|

The DALN in classrooms: A questionnaire

Overall, questionnaire results reveal that the DALN can be used by instructors and students to meet a wide range of pedagogical, institutional, community, and personal goals, from academic research and analysis to preservation of community to personal expression. Questionnaire responses reflected the concerns of Branch (1998), Elbow (2002), and others: there is a need to attend to the personal aspects of teaching and learning in order for education (and academic spaces, which tend to be impersonal) to make an impact for both students and teachers—and I argue, based on the questionnaire responses, the DALN is one possible resource that may help teachers and students to surf the binaries of openness/restriction, expert-direction/self-direction, and academic/personal in useful ways.3

The breakdown of course offerings mentioned by questionnaire participants was similar to the responses found by Comer & Harker (2015): first-year writing courses (including honors sections) were the primary site where questionnaire participants used the DALN (n=7) in college classrooms. However, questionnaire responses indicated that the DALN was also used in graduate courses (n=1) and mixed graduate/undergraduate courses (n=2), advanced composition (n=2) and upper level undergraduate courses, including business/workplace writing (n=2), digital media/multimedia composing (n=2), introduction to digital media studies (n=1), global communication (n=1), and English special topics in literacy (n=1).

More than half of questionnaire respondents (n=5) positioned the process of collecting and telling personal literacy narratives as a service to the composition and literacy studies communities as well as a service to broader understandings of literacy, suggesting that the DALN provides a platform and inspiration for service-learning and other community-focused pedagogies. Two participants, Harold and Karen, specifically noted that their DALN-focused courses contained a service-learning component, even if the courses have not been officially designated by their institutions as service-learning courses. Service learning integrates teaching, learning, and community service, emphasizing reflection, civic responsibility, and community collaboration to create meaningful educational and civic experiences. Karen indicated that the DALN lends itself to this type of community-based use because it is so focused on communities and literacy-in-context (Karen, 2014, personal communication).

Responses discussing service-learning justified the openness of the questionnaire. The DALN is used in ways both anticipated and unanticipated, and if I had not provided an open text box for participants to supply additional information not explicitly mentioned in the questionnaire, I may not have learned about the service-learning angle that some participants used with the DALN or the DALN service-learning projects and courses that some of the questionnaire participants taught. The openness of the questionnaire allowed the participants to be more self-directed and personal and identify what information and details they felt were most important to them, their students, and their uses of the DALN.

Though questionnaire participants generally did not explicitly position the DALN within binaries, the responses overall highlighted or illustrated binaries that the DALN reflects and resists. For example, in some responses participants focused on the benefits of the DALN’s openness, yet in other responses they also suggested that there be more control or restriction in order to improve users’ and contributors’ experiences. Rather than see the simultaneous calls for openness and restriction as a contradiction, I understand this as evidence of the queerness of the DALN—how it both reflects and resists simplistic binaries—and the queerness of working with it.

Using the DALN to connect our classrooms and communities can provide a queer learning space, allowing us to move between dominant educational binaries such as self-direction/expert-direction, impersonalness/personalness, and restriction/openness as students and community members engage, learn, and reflect on learning, literacy, community, and the power of the personal.

Though not specifically mentioned by any questionnaire participants, a version of an OSU general education course English 2367 (Literacy Narratives of Black Columbus) has been taught at The Ohio State University’s Department of African American and African Studies Community Extension Center. OSU undergraduates, graduate students, and local community members learned side by side, eventually collecting narratives from subsets of the broader African-American community such as church elders and musicians. Using the DALN as a way to connect students and the communities in which they live is a way to bridge between the classroom and the public, queering popular understandings of when and where teaching, learning, and knowledge production take place, and who has the right to claim authority and expertise. Teaching university courses (for credit) in the community in a community center with a mix of traditional undergraduates, graduate students, and community members is pretty queer. The DALN’s valuing of openness, personalness, and self-direction makes it an especially useful resource for queer learning spaces because it can be used to disrupt and exploit power hierarchies that govern educational spaces.

Ultimately, my questionnaire participants revealed that there are many ways to honor their own, other scholars’, their students’, and disciplinary expertise, and the DALN was one resource for doing so. According to questionnaire responses, the DALN’s structure—its personal, open, self-directed nature—provides advantages as well as disadvantages for users and classroom application. The tensions between personalness and academic (which manifests as impersonalness) were also evident in Laura’s questionnaire responses. When asked “What role, if any, do personal stories play into your understanding of the following… literacy, your classes/courses in terms of content (readings, lesson plans, informal and formal activities, examples/models, research projects, assignments, research)?” Laura responded, “Personal stories of others or my own play a vital role in helping connect with and relate to subject matter such as literacy, course content, and research. Understanding only the theory without real application and stories can be meaningless” (2013, questionnaire). For Laura, personal stories had the power to illuminate relatively impersonal academic work and make it more meaningful for all involved.

However, her response to the question, “How do you introduce and describe the DALN and literacy narratives to your students?” did not reflect the personal aspect of the DALN. Laura said, “I… explain the DALN as a nation-wide [sic] database of literacy narratives intended for use by academic researchers. I stress that… the database is publicly available, though intended for academic use” (emphasis added, 2013, questionnaire). By stressing researchers and academic use, Laura placed the DALN’s value squarely in the academic, expert realm, which seemed to obscure the non-academic or personal use and significance of the DALN. At the same time, as noted above, in her other responses, Laura emphasized the importance of personal experiences and knowledges for understanding literacy. So although Laura did not explicitly identify the binary of academic/personal, her responses reveal that she surfs between these binary concepts in order to understand and use the DALN. An instructor could point to the tensions between personal, impersonal, academic to explore what it means and looks like to say yes to both/and.

The DALN’s queerness—the ways in which its structure facilitates surfing between various binaristic values—could allow it to become an invaluable resource for teaching composition and literacy (and related research). As 21st-Century education becomes more digitally-based and moves more and more to online spaces, with miles (and even countries) separating instructors and students from one another, the DALN’s open access and self-directed nature provides one way to engage students and instructors across the miles. The rise of both online education and Massively Open Online Courses (MOOCs) requires resources and projects that are accessible to all students, regardless of how far flung they may be, and the DALN could be one of the resources that composition instructors turn to for their online courses, including MOOCs. The DALN is well positioned for online courses due not only to its open and accessible nature but also to the range of resources the DALN website provides. In some ways online education tends to be more personalized and personal than traditional classroom-based education (McKee, 2010), though MOOCs, with hundreds or even thousands of participants, can provide a less personal experience than the conventional lecture hall. Perhaps the DALN could queer online education—MOOCs especially—by providing a public and academic space for exploring and sharing personal knowledges and experiences.

Practically, then, instructors can use the DALN and its contents to meet a variety of goals, and the structure of the DALN provides opportunities for users to inhabit a range of positions in the research and composing processes. One questionnaire participant, Harold, contended that the DALN could be used to help students not only “serve their communities and learn about literacy,” but also teach about and practice qualitative research, such as “conduct[ing] oral history field work [and] writ[ing] about primary materials in a research/writing class” (2013, questionnaire). Other participants, such as Brian, argued that using the DALN in their classes provided the opportunity for students to take on the role of researchers, informants, and writers all within a single class. Brian said that he has tried to “emulate the DALN ‘life cycle’ on a smaller scale: going from the submission phase, to the collection phase, and finally to the research phase seemed tidy… it made sense to have my students play these different roles so that they could consider literacy from multiple angles” (2013, questionnaire). Users and contributors can use their own self-direction for exploring and understanding the DALN and so too can student researchers.

In many ways, student and teacher movement between different subject positions can help disrupt the teacher-student hierarchy by placing more emphasis (and value) on students’ (non-expert) ideas, interests, and knowledges. The ability to use one resource, such as the DALN, to inhabit different subject positions within a single course or project is queer; in a majority of classrooms, students are learners and perhaps researchers, but taking on the role of experts and contributors to broader public knowledge is not a standard component of most classrooms.

Perhaps most queer about the DALN is how it can be used to breakdown the perceived gulf between classrooms and the broader world. The DALN, questionnaire respondents indicated, was one way for students to share their personal knowledge and experiences beyond the walls of the classroom and see themselves as a kind of expert and perhaps feel a greater stake in their work with the DALN. Though Beth voiced concerns about having students submit to the DALN due to issues with truly informed consent, she said that students generally enjoy “the feeling that they are contributing their own [personal stories and knowledge] to public knowledge” (2013, questionnaire). Other respondents echoed this sentiment. For example, Sue said that she used the DALN in classes because it “provide[d] an opportunity for students to become published themselves, potentially part of someone else’s research into this topic” (2013, questionnaire). Christopher said the DALN “provides an added benefit” to the classroom study of literacy: “after analyzing and engaging with narratives from the DALN they get a chance to contribute to it. There’s no other resource like this with respect to literacy and literacy studies more generally” ( 2013, questionnaire). Sue, Beth, and Christopher contended that when students submit narratives to the DALN, their personal stories become part of the public and academic knowledge on literacy that others may then use to inform their own understandings of literacy. Students rather than teachers become literacy experts using self-direction to shape the content, implications, arguments, and accessibility of their personal DALN contributions.

Based on the questionnaire responses, I argue that the DALN may provide one way to shift the emphasis from instructor and academic experts and expert-direction to the personal expertise, situated knowledges, and direction of selves—students and other so-called non-experts. Though other archives may provide opportunities to curate or create a collection within individual research projects, most archives do not allow any individual to contribute to archives without expert permission and without following strict guidelines. Student use of and contribution to the DALN can help expose the artificiality of the expert/self binary and facilitate movement between experts (teachers, researchers, and scholars) and selves (students and novices). In the process, the binary of expert/self is not dismantled but it is queered. The artificiality of the either/or choice is exposed as false and replaced with the options of both/and and neither.

Uncovering the Values of the Archive

|

The DALN blog’s (thedaln.wordpress.com) resource section provides a variety of links and suggestions for instructors, students, and anyone else who desires ways to engage with the DALN and its narratives. The college-level assignments and activities illustrate the ways instructors may use the DALN to navigate between the dominant binaries that have been discussed throughout this project such as academic/personal, expert(direction)/self(direction), and restriction/openness. The DALN’s resources also demonstrate some potential uses of the DALN in classrooms, including qualitative research, multimedia composing, rhetorical analyses, and personal and critical reflection, all of which could be used to facilitate synchronous and asynchronous learning. However, relying on only the activities and resources provided by the DALN would be a disservice to the possibilities for the DALN. Part of my argument about the DALN rests on its flexibility, on its queerness, on its ability to be used differently depending on the self-direction and whims of its users and contributors.

The key to using the DALN to queer classrooms is ensuring that student knowledge and experience are at the center of the intellectual work, regardless of whether these prompts are used for online or face-to-face courses, and truly, that is what I argue is a major (queer) contribution of the DALN: a disruption of the hierarchies that place students and their knowledges below instructors or experts and their knowledges.4 Just as online education challenges traditional notions of education and composition, so too does the DALN.

The queerness of the DALN and the ways in which it may be used queerly may provide the metaphorical and literal space to re-imagine the relationships between literacy, identity, power, and the dominant binaries that shape archives, literacy, and associated values. I contend that the DALN’s position provides an opportunity for instructors and others to focus “not [on] the correctness or prevalence of one or the other side but, rather, the persistence of the deadlock itself” (Sedgwick, 1990, p. 91). As this chapter has endeavored to demonstrate, drawing attention to the “deadlock” of dominant binary values—that is, the necessity of both/and can become the basis for for choosing both/and rather than either/or and open up the possibilities for archives, personal narratives, and composition.

Overall, the DALN pushes against the dominant binaries of archives by embracing the queer practice of “surfing the binaries” of both/and. This position provides the room for contributors and users of the DALN to push the connotation and denotation of archives, research, literacy, and even queer, expanding the ways we understand, engage with, and use these spaces, actions, and concepts.

Concluding, but only beginning

Amy Winans (2006) argues, “A queer pedagogy draws attention to the parameters of questioning, thus highlighting the process of normalization as it draws attention to the places where thinking stops” (p. 113). The DALN may be used in our classrooms to:

- highlight the implicit values that shape those spaces and related spaces (such as archives);

- discover and compare expert-authored and self-authored truths of literacy; and

- identify the spaces where our thinking about literacy, archives, research, and classrooms has been stunted.

A queer pedagogy is a “queer studying” (Boellstorff, 2010), and this chapter has been a “queer studying” of the DALN and literacy. Similar to queer theory and queer communities, the DALN, its narratives, and its narrators “borro[w] refashion[n], and retell[l]” (Plummer, 2005, p. 369) dominant and minority narratives about archives, literacy, composition, and identities, helping draw attention to the edges, the contradictions, and the excess of meaning.

The possibilities for the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives are limited (primarily) by the imaginations and desires of those who contribute to and use the DALN. Though it is a digital archives of personal literacy narratives, the small stories shared during a literacy narrative can cover almost any topic or issue, both related and unrelated to literacy. DALN narratives have the potential to disrupt dominant narratives and discourses about literacy, identity, and who has the right (and privilege) to contribute to the public record about literacy because many DALN narratives examine “personal issues of being, becoming, and belonging in contextual and relational analyses of their situated experiences” with literacy (Grace & Benson, 1999, p. 93). Personal contextualization can result in an open interpretation of what literacy is, can, and does for people as well as what is appropriate for archives. The DALN demonstrates the usefulness and power of both/and in academic spaces. Ultimately, due to its queer values, I believe the DALN can help us reimagine the role of archives and literacy narratives in a range of classrooms.

Notes

- The Society of American Archivists’ glossary notes that using the term archive (without the –s) as a noun is generally disapproved of by U.S. and Canadian archivists, but is commonly used in other English-speaking countries. Archive (without the –s) is used as a noun throughout professional publications, perhaps because many professional publications include scholars and archivists from the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and a variety of other countries who write and publish in English.↵

- Space is still a concern, though. For example, in 2011, contributors and field researchers could not upload narratives to the DALN because it had filled the digital storage amount provided by the Ohio Digital Resource Commons. ↵

- After initially coding questionnaire responses, I realized that though impersonal has been useful for discussing the expectations for and values of archives and literacy narratives, impersonal is not as useful as the code academic for characterizing questionnaire responses related to teaching and research. Teaching is inherently interpersonal/personal, so impersonalness does not quite fit When academic work—such as research—is presented or published, research is often as an impersonal, objective process (though composition studies is one field where the personal aspects of academic work tends to be a little more visible). So academic is often related to impersonal though they are completely or always synonymous.↵

- I must mention assessment here: in most classrooms, assessment happens unidirectionally, from instructor to student, with instructors evaluating and grading students and their work. There are ways to disrupt this process as well, such as students and instructors collaboratively developing rubrics and grading schema so that the assessment guidelines reflect the needs and ideas of both students and instructors; and basing grades on an average of instructors’ assessments and students’ self-assessment or peers’ assessments. These methods could be used with or without using the DALN.↵

References

Alexander, J. (1999a). Introduction to the special issue: Queer values, Beyond identity. Journal of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity, 4(4), 287-292.

Alexander, J. (1999b). Beyond identity: Queer values and community. Journal of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity, 4(4), 293-314.

Alexander, K. P. (2011). Successes, victims, and prodigies: “Master” and “little” cultural narratives in the literacy narrative genre. College Composition and Communication, 62(4), 608-633.

Ancestry.com. (n.d.). Genealogy, family trees & family history records at Ancestry.com. Retrieved from http://www.ancestry.com/

Apple, A. (2010). From drag king to just a king. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/774cb3f8-b226-4763-8832-b0b27dc9735a

Bloom, L. Z. (1998). Composition studies as a creative art. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Blouin, F. X., & Rosenberg, W. G. (2011). Processing the past: Contesting authority in history and the archives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Boellstorff, T. (2010). Queer techne: Two theses on methodology and queer studies. In K. Browne & C. J. Nash (Eds.), Queer methods and methodologies: Intersecting queer theories and social science research (pp. 215-230). Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate.

Bly, L., & Wooten, K. (Eds.). (2012). Make your own history: Documenting feminist and queer activism in the 21st century. Los Angeles, CA: Litwin Books.

Brandt, D., Cushman, E., Gere, A. R., Herrington, A., Miller, R. E., Villanueva, V., Lu, M., & Kirsch, G. (2001). The politics of the personal: Storying our lives against the grain. Symposium Collective. College English, 64(1), 41-62.

Carter, J. (2015). I’m afraid I don’t have a very good story. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/32a8d071-6457-48c0-8fd6-32169c979b17

Comer, K., & Harker, M. (2015). The pedagogy of the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives: A survey. Computers and Composition, 35, 65-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.compcom.2015.01.001

Cook, T., & Schwartz, J. M. (2002). Archives, records, and power: From (postmodern) theory to (archival) performance. Archival Science, 2(3-4), 171-185. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435620

Cook, T. (2000). Archival science and postmodernism: New formulations for old concepts. Archival Science, 1(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435636

Corti, L. (2004). Archival research. In M. S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. F. Liao (Eds.), The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cvetkovich, A. (2003). An archive of feelings: Trauma, sexuality, and lesbian public cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cvetkovich, A. (2012). Queer archival futures. E-misférica, 9(1/2). Retrieved from http://hemisphericinstitute.org/hemi/en/e-misferica-91/cvetkovich

Danbolt, M. (2010). We’re here! We’re queer? Activist archives and archival activism. Lambda Nordica, 3-4, 90-118. Retrieved from http://www.lambdanordica.se/artikelarkiv_sokresultat.php?lang=en&fields[]=art_id&arkivsok=356#resultat

Davy, K. (2008). Cultural memory and the lesbian archive. In G. Kirsch & L. Rohan (Eds.), Beyond the archives: Research as a lived process (pp. 128-138). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Derrida, J. (1976). Of grammatology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Derrida, J. (1982). Margins of philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1994). The souls of Black folks. Chicago: Dover Publications.

Eichhorn, K. (2008). Archival genres: Gathering texts and reading spaces. Invisible Culture, 12. Retrieved from http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue_12/index.html

Eichhorn, K. (2013). The archival turn in feminism: Outrage in order. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Evans, M. J. (2007). Archives of the people, by the people, for the people. The American Archivist, 70(Fall/Winter), 387-400.

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777-795.

Grace, A. P., & Benson, F. J. (2000). Using autobiographical queer life narratives of teachers to connect personal, political and pedagogical spaces. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 4(2), 89-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/136031100284830

Hale, J. (1996). Are lesbisans women? Hypatia, 11(2), 94-121.

Halberstam, J. (2005). In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives. New York: New York University Press.

Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. Durham: Duke University Press.

Harper, P. B., White, E. F. & Cerulla, M. (1990). Multi/Queer/Culture. Radical America, 24(4): 27-37.

Hawisher, G. E., & Selfe, C. L. (2004). Becoming literate in the information age: Cultural ecologies and the literacies of technology. College Composition and Communication, 55(4), 642-692.

hooks, b. (1984). Feminist theory: From margins to center. Boston: South End Press.

HoratioCraver. (2009). My life. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/0740e597-2971-4851-a4a2-6b4a18e6180c

Hui, Y. (2013, May 22). Archivist manifesto. Mute: Magazine, Book Publishers and Media Technologists. Retrieved from http://www.metamute.org/editorial/lab/archivist-manifesto

Hunter, G. S. (1997). Developing and maintaining practical archives: A how-to-do-it manual. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman.

Jenkinson, H. (1937). A manual of archive administration (Internet archive). Retrieved from http://archive.org/manualofarchivea00iljenk

Jody. (2009). Reading for pleasure. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/0e389e44-c775-43be-885a-e338b3e7af75

Kirsch, G., & Rohan, L. (Eds.). (2008). Beyond the archives: Research as a lived process. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Kumbier, A. (2014). Ephemeral material: Queering the archive. Sacramento: Litwin Books, LLC.

Luhmann, S. (1998). Queering/querying pedagogy? Or, pedagogy is a pretty queer thing. In W. Pinar (Ed.), Queer theory in education (pp. 141-156). Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Manoff, M. (2004). Theories of the archive from across the disciplines. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 4(1), 9-25. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0015

Martin, P. (2011). Paid to be gay. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/1306852d-8680-4de6-af9e-ae8467a616a8

McKee, T. (2010). Thirty years of distance education: Personal reflections. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11(2), 100-109.

Mejia, J. A. (2006). Responses to Richard Fulkerson, “Composition at the turn of the twenty-first century.” College Composition and Communication, 57(4), 730-762.

Moghaddam, R. Z., Bongen, K., & Twidale, M. (2010). Open source interface politics: Identity, acceptance, trust, and lobbying. Retrieved from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/15232

Monks-Leeson, E. (2011). Archives on the Internet: Representing contexts and provenance from repository to website. The American Archivist, 74(Spring/Summer), 38-57.

Nelson, N. L., Shaw, S., Deromedi, N., Shallcross, M., Belden, M., Esposito, J., ... Pyatt, T. (2012). Managing born-digital special collections and archival materials (Executive Summary, pp. 1-19, Publication No. SPEC Kit 328). Washington DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Occupy Archive. (n.d.). Omeka RSS. Retrieved from http://occupyarchive.org/

ONE Archives Foundation. (2012). ONE Archives at the USC libraries. Retrieved from http://www.onearchives.org/

Pearce-Moses, R. (2005). A glossary of archival and records terminology. Society of American archivists. Retrieved from http://www2.archivists.org/glossary

Potts, B. (2013). Life story of Byron L. Potts. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/c6dbefc1-8d5b-4247-a61b-6da6e1383729

Plummer, K. (2005). Critical humanism and queer theory. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Pratt, M. B. (1995). S/He. Ann Arbor, MI: Firebrand Books.

Prelinger, R. (2009). The appearance of archives. In P. Snickars & P. Vonderau (Eds.), The YouTube reader. Retrieved from http://www.youtubereader.com/

QZAP: Queer Zine Archive Project. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.qzap.org/v8/

Ramsey, A. E., Sharer, W., L’Eplattenier, B., & Mastrangelo, L. (Eds.). (2010). Working in the archives: Practical research methods for rhetoric and composition. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Rawson, K.J. (2012). Archive this! Queering the archive. In K Powell & P. Takayoshi (Eds.) Practicing research in writing studies. New York: Hampton Press.

Reja, U., Manfreda, K. L., Hlebec, V., & Vehovar, V. (2003). Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires. Developments in Applied Statistics, 19, 159-177.

Renn, K. A. (2010). LGBT and queer research in higher education: The state and status of the field. Educational Researcher, 39(2), 132-141. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X10362579

Rhodes, J. (2004). Homo orgio: A queertext manifesto. Computers and Composition, 21(3): 385-388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2004.05.001

Rhodes, J., & Alexander, J. (2012). Queered. Technoculture, 12. Retrieved from http://tcjournal.org/drupal/vol2/queered

Schellenberg, T. R. (2003). Modern archives: Principles and techniques [Reissue]. Retrieved from files.archivists.org/pubs/free/ModernArchives-Schellenberg.pdf

Schellenberg, T. R. (Theodore R.), 1903-1970. (2011). Retrieved from http://archivopedia.com/wiki/index.php?title=Schellenberg%2C_T._R._%28Theodore_R.%29%2C_1903-1970

Schlasko, G. D. (2005). Queer (v.) pedagogy. Equity & Excellence in Education, 38(2), 123-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680590935098

Sedgwick, E. K. (1990). Epistemology of the closet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sedgwick, E.K. (1994). Tendencies. Durham: Duke University Press.

Selfe, C.L., & Selfe, R. (1994). The politics of the interface. College Composition and Communication, 45(4), 480-504.

Shingledecker, B. (2012). My queer literacy narrative. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/93555531-42d9-4521-b1e3-1e24c463f65d

Singleton, S. (2010). Finding myself. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/c1072648-8daf-4663-8919-1b2fd31d5f3f

Singleton, S. (2015). The first word is love. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/ebcc4f82-5405-4454-9a31-fe358e98396d

Skinnell, J. (2010). Circuitry in motion: Rhetoric(al) moves in YouTube’s archive. Enculturation, 8. Retrieved from enculturation.gmu.edu/circuitry-in-motion.

Society of American Archivists Council. (2011). Core values of archivists. Retrieved from http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics#.V3QLzlcVdFI

Sohn, K. K. (2006). Whistlin’ and crowin’ women of Appalachia: Literacy practices since college. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Spivak, G. C. (1985). The Rani of Sirmur: An essay in reading the archives. History and Theory, 24(3), 247-272.

Stapleton, R. (1983). Jenkinson and Schellenberg: A comparison. Archiviaria, 17, 75-85.

Steedman, C. (2001). Dust. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Street, B. V. (Ed.). (2005). Literacies across educational contexts: Mediating learning and teaching. Philadelphia: Caslon Pub.

Street, B. V. (1995). Social literacies: Critical approaches to literacy in development, ethnography, and education. London: Longman.

Taylor, A. (2010). Alexis Taylor. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/7d78985b-4be3-4d0b-be0f-2e50004cda1e

Theimer, K. (2009, August 13). Archives 2.0: An introduction. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/ktheimer/archives-20-an-introduction

Theimer, K. (2011). What is the meaning of Archives 2.0? The American Archivist, 74(Spring/Summer), 58-68.

Ulman, H. L. (2013a). Reading the DALN database: Narrative, metadata, and interpretation. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Ulman, H. L. (2013b). A brief introduction to the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN). In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Ulman, H. L., DeWitt, S. L., & Self, C. L. (Eds.) (2013). Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

University Archives. (2013, August 22). The Ohio State University Libraries. Retrieved from https://library.osu.edu/archives

Vocat, D. (n.d.) Queer by choice? Daryl Vocat. Retrieved from http://www.darylvocat.com/qbc/

Warner, M. (1993). Introduction. In Fear of a queer planet: Queer politics and social theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Web 2.0. (2013, August). Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0

Weeks, J. (1995). Invented moralities: Sexual values in an age of uncertainty. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Werner, M. L., & Voss, P. J. (1999). Toward a poetics of the archive. Studies in the Literary Imagination, 32(1), i-viii.

Williams, E. (2013). I wrote what? Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/6f311693-d6ea-457b-957d-db6012d50aae

Winans, A. (2006). Queering pedagogy in the English classroom: Engaging with the places where thinking stops. Pedagogy, 6(1): 103-122.

Wright, J. (2010, October 5). Just what is an archives, anyway? The bigger picture: Visual archives and the Smithsonian. Retrieved from http://siarchives.si.edu/blog/just-what-archives-anyway