Social Media, the Classroom, and Literacy Sponsorship: An Analysis of DALN Narratives with Positioning Theory

JEN MICHAELS

Abstract

When teachers introduce new technologies into the classroom, they face a series of challenges: assessing possible technologies, selecting technologies that may support learning, and supporting students as they use those technologies for scholarly purposes. The Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives makes it possible to identify behaviors and attitudes that help some teachers feel supported and confident in selecting and leveraging technologies in their teaching. In this article, I model this identification process by analyzing three narratives from the DALN, all submitted by teachers of composition who use social media to support their scholarship. Using positioning theory (Bamberg, 1998, 2007; Harré & van Longenhove, 1999) and the metaphor of literacy sponsorship (Brandt, 1998) as critical lenses, I examine how the narrators describe human mentorship as a contributor to their use of social media to support scholarship. Across these narratives, four shared traits of effective mentorship emerge: 1) the mentor and mentee share an intellectual or practical goal; 2) the mentor seems willing to maintain the mentorship relationship over time; 3) the mentor encourages meaningful choice among multiple technologies that may suit the task at hand; and 4) the mentee perceives the mentor as being proficient with the technology at hand. I discuss how these four mentorship traits manifest in the narratives, then discuss they suggest possible improvements for teaching practice. I also discuss how positioning theory and literacy sponsorship might be useful frameworks for classroom analysis of DALN narratives.

***

Introduction

Throughout The Archive as Classroom, scholars describe ways to use the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives to enhance student learning. This chapter focuses on a different but closely related topic: how the DALN might help us examine and improve teaching practices, which in turn affect student learning. It demonstrates one method of using DALN narratives to explore teacher-scholars’ description of their teaching practices. In particular, I focus on stories from teacher-scholars about human mentors who encourage their use of social media for scholarly purposes. Social media may be a relatively new wave of technologies, but mentorship is a time-honored practice. By addressing mentorship and social media together, I hope to elicit lessons about mentorship that may cross beyond the domain of social media, yet are also useful for teachers who are evaluating new technologies for scholarly purposes.

Using the DALN, I identified three video narratives from teacher-scholars in various contexts, all of whom describe how mentors impact their use of social media for teaching and other scholarly projects. The three narratives examined in this chapter share a common focus on human mentorship. Each narrator describes either themselves, or someone who encourages teacher-scholars to embrace social media in collegiate contexts. To be clear, these narratives were not solicited by this study’s author as part of a research project; rather, the narrator assembled this group of narratives based on searches for particular keywords in the DALN, as described in the methods section below.1

To rhetorically analyze these narratives, I use positioning theory, a conceptual framework drawn from narrative theory and sociology. In the field of sociology, positioning theory (Harré & van Longenhove, 1999) examines how individuals use language and stories to position themselves relative to other people and to situate themselves within social discourses. To focus more specifically on the rhetorical dimensions of positioning theory in a literacy narrative, I employ a three-tiered model for positioning theory articulated by narrative theorist Michael Bamberg (1998, 2007), which encourages attention to

- the position of the narrator as a character within the narrative,

- the position of the narrator to the audience, and

- the positioning of the narrator as a self who represents that selfhood in a certain way.

Bamberg’s approach to positioning provides a model for examining the rhetorical ways that story narrators position themselves in their tellings of stories. For that reason, Bamberg’s work has influenced a variety of recent scholarship related to literacy, rhetoric, and composition, including the rhetoric of the literacy myth in Appalachia (Bryson, 2012), the dynamics of multilingual literacies (Frost & Blum Malley, 2013), and the dynamics of cultural schemas and pedagogical narratives (Sharma, 2015). Some of those studies, and many others, specifically apply Bamberg’s work to literacy narratives from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives, as I describe below in the literature review. In this study, Bamberg’s three-tiered model for positioning provides a framework for examining how narrators and story characters are being represented in stories about social media and teaching.

My analysis of these three narratives through the lens of positioning theory (Bamberg, 1998, 2007; Harré & van Longenhove, 1999)—and informed by Deborah Brandt’s (1998) metaphor of literacy sponsorship—identifies four traits of social-media mentorship that manifest in all three narratives:

- the mentor and mentee share an intellectual or practical goal,

- the mentor seems willing to maintain the mentorship relationship over time,

- the mentor encourages meaningful choice among multiple technologies that may suit the task at hand, and

- the mentee perceives the mentor as being proficient with the technology at hand.

As I describe in the chapter’s concluding sections, these four traits suggest possible best practices for teaching with social media. They provide a starting place for considering how teachers can support students as they use social media in scholarly contexts.

Below, I discuss why this investigation focuses particularly on social media and what advantages that focus offers. The chapter then reviews literature relevant to narratives and the DALN, including a discussion of related research in rhetoric and composition and a discussion of narrative analysis as a research method. After exploring the analytic value of positioning theory and the concept of literacy sponsorship for DALN narratives, I demonstrate the results via a close-reading each of the three DALN narratives in the data set. Finally, the chapter closes with possible implications for further research and suggestions for teachers who hope to explore these mentorship principles in their teaching.

SOCIAL MEDIA IN THE CLASSROOM: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

To date, a number of composition scholars have examined social media as a contemporary set of literacy practices that offer potential affordances for composition teaching. Although the term social media is rarely defined in composition scholarship, for purposes of this article, we will define it broadly as “a category of online technologies that facilitate the creation and sharing of online content.” The narratives analyzed in this sample set mention popular tools that are widely accepted as being “social media,” including the social-networking platforms Facebook and Twitter, weblogs, social-bookmarking sites such as de.li.cious and Diigo, and social citation management tools like Zotero.

Composition scholars have considered social media as a body of technologies that may be useful for composition teaching. For example, scholars have described social media as part of a Web 2.0 movement that privileges user-generated, user-published, and user-circulated content (DeVoss & Porter, 2006; Gerben, 2009). Others have defined social media as a set of technologies through which information can circulate quickly and change in rhetorically complex ways (Sheridan, Ridolfo, & Michel, 2012). As a result, scholars uphold social media as a space where students can engage with discourses of identity, politics, and social construction (Dubisar & Palmeri, 2010; Maranto & Barton, 2010; Swartz, 2010; Dadurka & Pigg, 2011; Potts & Jones, 2011; Buck, 2012; Vie, 2014). In some cases, these scholars even suggest that social media is a discourse that can contribute to the public good and to democratic freedom. In her article “Why Teachers Must Learn: Student Innovation as a Driving Factor in the Future of the Web,” Erin Frost (2011) passionately defends her students’ voluntary decision to use Facebook in their research:

Web-based social media are a major shaping factor in the future composition classroom. These media are important not only because they are ubiquitous, but also because they lend themselves to the sorts of inquiry privileged by composition instructors. We have seen time and again—through Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and more—the ways that Web-based media can be used to promote a democratic ideal, a common movement. ( p. 270)

But as Frost’s statement implies, composition teachers have found more than just rhetorically and civically rich engagement through social media. Some teachers have also found social media useful at a functional level, providing tools that are helpful for coordinating common tasks in the composition classroom. For example, scholars have described how social media can be used to organize and streamline research processes (Purdy, 2010), visualize complex information (Sorapure, 2010), coordinate collaborations between multiple people (Moxley & Meehan, 2007; Frost, 2011), and host critical conversation around sources, texts, or classroom projects (Balzhiser et al., 2011; Kaufer, Gunawardena, Tan, & Cheek, 2011; Davis & Marsh, 2012; Coad, 2013).

Despite the many affordances scholars ascribe to social media, there are also challenges to using social media for scholarship and teaching. For example, some scholars describe a crisis of confidence among teacher-scholars, in which teacher-scholars envision themselves as being hopelessly “behind the times” and unable to acclimate to social media (Vie, 2008; McClure, 2014). Other scholars have pointed to gaps in our understanding about exactly how online learning takes place and what constitutes effective practices (Sackey, Nguyen, & Grabill, 2014), which is a potential barrier to using social media in the classroom.

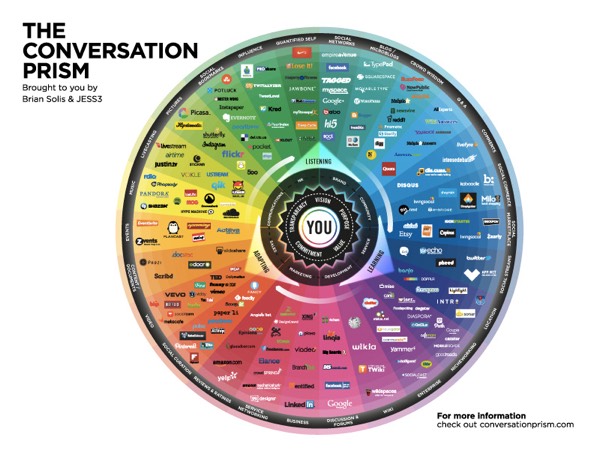

To this list of challenges, we might add the potential for social media to overwhelm users with its breadth and depth. Social media is a diverse category of online sites and services that evolves quickly and changes often. To get a sense of the category’s breadth, depth, and speed of evolution, we might consult anthropologist Brian Solis’s (2016) web visualization titled “The Conversation Prism” (see Figure 2 below), which he describes as “a visual map of the social media landscape.” As of 2013, Solis’s prism included logos representing over 185 social-media tools. Solis notes that in his most recent revision, he deleted 122 logos from the visualization and added 111 new ones. This high number of additions and deletions speaks to the speed at which social media evolves, both in terms of the number of tools available to users and the connotations that the term social media carries over time.

In short, no matter how one defines the term social media, there are many potential tools to assess for classroom potential. And when there are many options available to someone, coupled with a potential sense that someone is “behind the times” and may have difficulty acclimating to a new tool, there may be reluctance or anxiety about uptaking a new tool (like social media) for scholarly purposes.

LITERATURE REVIEW: THE DALN, POSITIONING THEORY, AND LITERACY SPONSORSHIP

This study’s data sample is three video narratives from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives, an open and publicly available archive of narratives about literacy. As the authors in the collection Stories that Speak to Us (DeWitt, Selfe, & Ulman, 2011) remind us, narratives are interpretations of lived experiences, not reflections of an objective truth or reality. But interpreted experiences have research value insofar as they help us understand how individuals perceive their lived experiences. In other words, the research value of DALN narratives is their subjectivity. By analyzing DALN narratives, we might find patterns in the ways that people narrate—and therefore represent to others—their subjective experiences.

My goal is to situate descriptions of social-media literacy practices in terms of their embedded cultural and historical contexts, a goal that underpins much of the scholarship associated with New Literacy Studies (Street, 1993). NLS scholars David Barton, Mary Hamilton, and Roz Ivaničc (2000) describe literacy practices as “usefully understood as existing in the relations between people, within groups and communities, rather than as a set of properties residing in individuals” (p. 8). In other words, by examining how an individual describes and conceptualizes their literacy practices, we can learn things about how literacy circulates in a larger context.

Previous scholars have established that analyzing small groups of narratives can yield valuable research findings on a variety of subjects. For example, Genevieve Critel (2013) used four DALN narratives to identify four common considerations in how minority women develop and perceive digital literacy practices. Krista Bryson (2012) used DALN narratives to explore how Appalachian identity interacts with Harvey Graff’s concept of the literacy myth. Other scholars, especially in the 2012 collection Stories that Speak to Us, have also used the DALN to explore the experiences of particular groups, including multilingual students, Black women, women with transnational literacy experiences, and many more (Frost & Malley, 2013; Buck & Hawisher, 2013; Voss, 2013; DeWitt, 2013).

There is also precedent for using the DALN to better understand how teachers and students interact with technological literacies. For example, in “Returning Adults in the Multimodal Classroom,” Lynn Reid (2015) describes how encountering stories from the DALN helped her become aware of contextual factors that influence how returning adult students experience digital composition assignments. Similarly, Kory Lawson Ching and Cynthia Carter Ching (2012) used technological narratives to explore what factors contributed to future teachers’ postures toward technology in the classroom. Julia Voss (2013) used literacy narratives to explore how students’ previous experiences with technology impact their perception of technology in college contexts.

In broader terms, composition scholars have long valued the literacy narrative as a means for students and teachers to share and reflect on experiences (Soliday, 1994; Scott, 1997; Tinberg, 1994). For example, Susan Kirtley (2012) invites her students to compose and reflect on literacy narratives about technology in order to encourage “revelations about their identities as writers and helping them better understand their best writing practices” (p. 192). A number of composition scholars have used their own literacy narratives to bolster ethnographic arguments about innovations in teaching, including in Peter Elbow’s (1973) Writing Without Teachers, Mike Rose’s (1999) Lives on the Boundary, Victor Villaneuva’s (1993) Bootstraps, and Linda Brodkey’s (1994) “Writing on the Bias.” More recently, in his video literacy narrative “Writing a Professional Life on Facebook,” Timothy Briggs (2013) demonstrates how he uses social media to connect and share ideas with colleagues across geographic distances (see image and video below).

These studies confirm that literacy narratives, including small sets of DALN narratives, can yield useful conclusions for understanding composition pedagogy and improving teaching practices. It is notable, however, that many of the above studies focus on literacy narratives that were created or solicited specifically for that research project. This project, like some others, uses narratives that were submitted to the DALN by their authors, independent of this research project. Indeed, all three narratives were submitted to the DALN months or years before this research project was even imagined. Thus, unifying these narratives for analysis requires the adoption of theoretical frameworks that would facilitate comparisons. For that, I turn to Deborah Brandt’s concept of literacy sponsorship.

Literacy Sponsorship in Narratives about Technology

Since this investigation focuses on mentorship relationships between two or more people, the study employs Deborah Brandt’s (1998, 2001) metaphor of literacy sponsor as a guidepost for thinking about mentorship. Brandt defines literacy sponsors as “agents… who enable, support, teach, and model, as well as recruit, regulate, suppress, or withhold literacy—and gain advantage by it in some way” (p. 19). To be clear, within the parameters of this study, the terms mentor and literacy sponsor are not assumed to be synonymous. Mentor tends to be a more generous and positive term, connoting a relationship in which a relative expert offers advice and support to a relative novice. Literacy sponsor, by contrast, more broadly interactions between two entities that might afford or constrain literacy practices. Brandt’s definition reminds us that literacy acquisition is always a motivated act on the part of the sponsor. Sponsors can encourage and enable access to literacies, but they can also constrain, suppress, or withhold literacy. And as some of the examples in this study reveal, even acts that a narrator might represent as “affording access” can also reveal dynamics of constraint, suppression, or withholding.

The lens of literacy sponsorship, then, helps us consider the complex ways that motivation and behavior affect the movement of technological literacies through a culture. Because the metaphor of literacy sponsorship broadly interrogates the ways that human beings afford or constrain each other’s access to literacy, this lens encourages attention to particular dynamics within a mentorship relationship. We are reminded to examine a mentor’s motivation and that motivation’s role in affording or constraining literacy. We are encouraged to consider not only what mentors support or provide to their mentees but also what they suppress or withhold. I return to this perspective on mentorship in the chapter section titled “Implications for Teaching,” where I consider how the four mentorship traits described in this article might intersect with teaching practice.

Literacy sponsorship is also a useful metaphor for describing composition instructors. Almost by definition, composition instructors are in the business of upholding particular literacies and suppressing others. After all, every teacher makes decisions about which literacy practices and technologies they’ll welcome in their classroom—and which they’ll discourage or actively forbid. This dynamic of support and affordance, as well as regulation and constraint, arguably applies to all literacies–including electronic literacies, as shown in Cynthia Selfe and Gail Hawisher’s (2004) Literate Lives in the Information Age. That study, which Selfe and Hawisher explicitly describe as being inspired by Brandt’s work, was followed by the more recent Transnational Literate Lives in Digital Times by Patrick Berry, Cynthia Selfe, and Gail Hawisher (2012). Therefore, there is significant precedent for using the concept of literacy sponsorship to examine how the motivated behaviors of individuals can influence developing or changing literacies in electronic environments.

As this study demonstrates, coupling literacy sponsorship with positioning theory lends a rhetorical dimension to our understanding of DALN narratives, one that reveals how the agency of non-human actants intersects with narrative to impact how we understand the centrality and purpose of literacy in electronic environments.

POSITIONING THEORY AS A NARRATIVE INTERPRETATION TOOL

To examine how DALN literacy narratives shed light on literacy sponsorship in social media environments, I draw on positioning theory, a conceptual framework from sociology that has connections to rhetorical theory. Positioning theory provides a methodology for examining how individuals use language and stories to position themselves relative to each other and within social discourses. Many scholars credit positioning theory’s genesis to Wendy Hollway’s (1984) work on social positioning between male and female individuals, but today, positioning theory is used by a variety of social scientists, discourse analysts, and narrative theorists. As it expanded in use, positioning theory has grown to more generally examine “the discursive construction of personal stories that make a person’s actions intelligible and relatively determinate as social acts and within which the members of the conversation have specific locations” (Harré & Van Langenhove, 1998, p. 16).

Much like some rhetorical theories about discourse, positioning theory considers people as motivated individuals who use their agency to position themselves in particular ways for particular purposes. For example, Davies and Harré (1998) suggest that positioning theory allows us to “think of ourselves as choosing subjects, locating ourselves in conversations… and bringing to those narratives our own subjective lived histories” (p. 41). Harré and van Langenhove (1998) emphasize that self-positioning can be deliberate and strategic, for which we must “assume that they [the speaker] have a goal in mind” (p. 25); we can similarly assume that attempts to force the positioning of others might also be deliberate. However, most versions of positioning theory recognize that positioning is not always deliberate, nor is it always in the full control of a single narrator. Thus, positioning theory allows for a fluid understanding of individual agency in a socio-cultural milieu, where outside forces and social structures help to shape an individual’s choices about positioning.

Michael G.V. Bamberg’s (1997) model for narrative positioning has particular relevance to studying DALN narratives. In “Positioning Between Structure and Performance,” Bamberg suggests a three-tiered approach that focuses on how the narrative itself can “intervene, so to speak, between the actual experience and the story” (p. 335). Bamberg suggests analyzing a narrator’s positioning at three levels:

- Level 1 (BPL #1): Narrator as character within the narrative and its story-world

- Level 2 (BPL #2): Narrator to an audience

- Level 3 (BPL #3): Narrator’s position of themselves to themselves

To take a simple example of this, suppose you are telling a scholarly colleague about this very book chapter. As you narrate your reading of the chapter, you represent yourself both as a character in the story (person reading the chapter, BPL #1) and someone who is narrating to them at that moment (the story’s narrator, BPL #2). You may also be positioning yourself as a scholar who is interested in ideas about teaching and technology, a state that perhaps predated your reading of this chapter and persists afterward (BPL #3). This example suggests how positioning theory might help us parse a narrative into its different simultaneous modes of representation. As we will see below, narrators do not always represent themselves the same way at all three levels. These differences in positioning provide a framework for considering how stories about mentors and mentees might reflect (or not reflect) stable traits of mentorship that may be generalizable beyond the individual narrative.

Although Bamberg’s scholarship about positioning has influenced a broad variety of ethnographic research that involves narrative (Vergaro, 2011; Riessman, 2002; Hamilton, 2005; Subhan, Hons, & Dip 2012), explicit use of his three-tiered framework for rhetorical analysis has seen limited to date in studies within literacy, rhetoric, and composition. However, Bamberg’s framework plays a prominent role in Amber Buck and Gail Hawisher’s (2013) “Mapping Transnational Literate Lives: Narratives, Languages and Histories.” In this piece, Buck and Hawisher use Bamberg’s model to examine how narrators position themselves and their literacies across multinational contexts. This study owes much to Buck and Hawisher’s analysis of how the narrators they examine position themselves to themselves and to the audience. I seek to build on that analysis model here by more systematically analyzing how each narrator in my study positions themselves in three different ways: as a character in a narrative, as a narrator to an audience, and as a rhetorical self.

STUDY METHODS

To identify literacy narratives relevant to this project, I used the Advanced Search function in the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. I began by focusing on the keyword social media, which I placed in quotation marks to avoid receiving search results for just the word social or just the word media. But as of November 2011 when I began gathering data, searching the DALN for “social media” yielded only 4 search results.2 To widen my data pool, I then added the names of two popular social-media tools to my search query:

“social media” OR Facebook OR Twitter

This search yielded a total of 35 possible archives for investigation.3 I reviewed each of these 35 submissions in turn, looking for evidence that the narrators self-described as teachers or scholars in a collegiate setting. At this point, I had seven archives remaining in the sample pool. I viewed those 7 narratives twice each, taking informal notes on any major themes in these narratives. At that point, I noticed that the three narratives in this study’s sample set shared a common theme of mentorship in social-media environments.

Having narrowed my data set to these three narratives, I began taking informal notes on the traits of mentorship that emerged across the data set. The four proposed traits were revised and made more specific through a systematic review of these three narratives, using this process:

- Review of each archive’s metadata, including titles, descriptions, keywords, and associated files

- Transcription of Marino (2010) and Chang (2010) with the software MovieCaptioner

- Review of the text transcript of Pignetti and Cochran’s (2009) narrative, already part of their DALN archive courtesy of TranscribeOhio

- Analysis of multimodal data from each video file, including attention to the narrators’ body language, voice tone and pitch, gestures, and posture

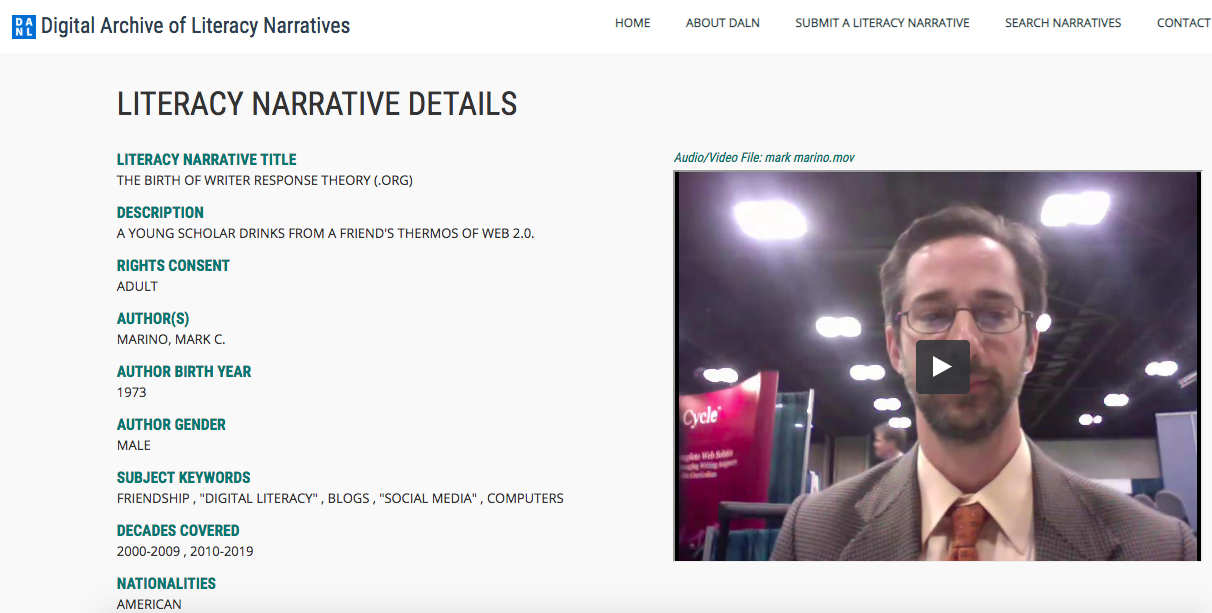

NARRATIVE #1: A MENTEE DESCRIBES HIS SOCIAL-MEDIA MENTOR

Of the three narratives in this study’s sample set, Mark Marino’s (2010) “The Birth of Writer Response Theory (.org)” most explicitly frames itself as a story about mentorship and social media. Indeed, early in the video, narrator Mark Marino states that the narrative is specifically about his mentor. Marino says that he writes “on a collaborative blog with with a person named Jeremy Douglass, and this story is about him.”

To put this in Bamberg’s terms, within the world of the narrative and his characters (BPL #1), Marino positions himself as a mentee and positions Douglass as a mentor. This positioning manifests both in the video narrative itself and in the archive’s metadata. For example, the video archive’s dc.description line alludes to a mentor-mentee dynamic between two characters: “a young scholar drinks from a friend’s thermos of Web 2.0.” Although Marino does not define the term Web 2.0 in his DALN archive or the narrative itself, evidence from the video suggests that he sees this term as closely related to social media, collaboration on user-generated content online, and participatory culture. Thus, even before an archive visitor views the video file, there is evidence that this narrative will involve two characters with disparate levels of knowledge about “Web 2.0.”

But while Marino positions his character within the story as someone who was mentored by Douglass (BPL Level #1), Marino positions himself to the audience as a teacher and scholar (BPL Level #2 and #3). Early in his video narrative, before mentioning Douglass, Marino introduces himself as “teach[ing] over at the University of Southern California at present” and being “involved with the Electronic Literature Organizatio… which promotes experimental literature” (see Video 2 below). He also mentions being a co-founder of the scholarly blog WriterResponseTheory.org, a project on which he collaborates with scholar Douglass. By beginning his narrative with this introduction, Marino positions himself with the audience as having been a teacher-scholar in the past and present. In other words, Marino is encouraging the audience to not only see him as a teacher and scholar at this moment in this narrative (BPL #2) but also as an ongoing state over time (BPL #3). This will become important momentarily when Marino delves into a story from the past, in which he portrays himself as a confused novice.

Having established his ongoing ethos as an active scholar and teacher, Marino then encourages his audience to concentrate on a particular character in the upcoming story. In fact, Marino states that this narrative is “a story about him [Jeremy Douglass]” (see Video 2 below). In other words, at this moment in the narrative, Marino uses his position as a narrator (BPL #1) to encourage the audience to position characters in the narrative in a certain kind of relationship (BPL #2).

Marino then begins recounting events from the past, positioning himself as a novice user of social media. Marino’s position as novice is reflected by both what he says and his body language and tone as he relates the story (see Video 2 above). For example, Marino relates that during a meeting with Douglass about a possible upcoming collaboration, Douglass suggested that the pair “should pull our social bookmarks together.” Marino responds to Douglass with the question, “What… would we be pulling together at that point?” When Marino re-enacts this moment of dialogue, his voice rises in pitch, he speaks more slowly than he was speaking before, his eyes widen, and he visibly shrugs his shoulders. This combination of voice effects and body language suggests that when Marino asked his question, he was trying to convey a sense of confusion and overwhelm. In short, Marino is calling for greater explanation and help from Douglass.

Marino then describes Douglass’s response, and this description frames Douglass as a mentor to Marino in social-media spaces. For example, Marino states that “we started talking about social bookmarking,” which implies that Douglass began explaining to Marino what the term social bookmarking means and demonstrating how some of the relevant online social bookmarking sites functioned. More specifically, Marino states that Douglass “proceeded to explain to me [about] social bookmarking” and used his computer to “pull up de.li.cious… and… Diigo,” two online social bookmarking tools, on his computer (see Video 3 below).

This mentor-mentee dynamic repeats several more times across the narrative, and each cycle reinforces Douglass’s position as mentor and Marino’s position as mentee. Marino describes Douglass asking Marino a series of questions, like “What is your Wiki platform of choice?” and “What is your free open-source educational platform of choice?” Marino describes his response as, “And I said I’m not—I’m not teaching any—I’m not, I don’t know the tools of which you speak.” This halting diction and syntax reinforces Marino’s character position as a novice in need of mentoring. Meanwhile, Marino describes Douglass as showing him “a million of things,” including social-media tools like Zotero (an online citation management system that has sharing capabilities) and Moodle (an open-source learning management system that facilitates sharing of content among users).

Narrative #1 and the Four Traits of Social-Media Mentorship

Having established that Marino portrays Douglass as a mentor figure, we can now turn to considering what attitudes or behaviors Marino ascribes to this mentor. Here is how Douglass’s behavior, as narrated by Marino, correlates with the four proposed traits of social-media mentorship in this chapter:

- The mentor and mentee share an intellectual or practical goal: Marino frames Douglass as his collaborator on Writerresponsetheory.org, stating that this entire conversation about social-media tools was undertaken in service of that project.

- The mentor seems willing to maintain the mentorship relationship over time: Although Marino does not explicitly state that he continues to receive support and mentorship from Douglass, he does state that he continued to collaborate with Douglass using the tools that Douglass introduced. In Marino’s words, “that [conversation] led to a collaboration on these very collaborative platforms that we later ended up studying more in depth on a blog, or through our bookmarks, or through our Zotero group… the list goes on.”

- The mentor encourages meaningful choice among multiple technologies that may suit the task at hand: Marino frames Douglass as introducing him to many tools. In at least one case, that of social bookmarking, Douglass shows Marino at least two different tools, Diigo and de.li.cious bookmarks.

- The mentee perceives the mentor as being proficient with the technology at hand: Marino describes Douglass as showing Marino “a million of things,” implying that Marino was struck not just with the particular tools Douglass suggested but also the variety of tools that Douglass displayed. Marino also comments on Douglass’s functional proficiency with the physical hardware at hand, noting that “very quickly, we were on the computer and his fingers were flying” as Douglass showed Marino a series of social-media tools.

Interestingly, at the very end of the narrative, Marino re-positions himself from a novice and mentee to a relative expert who mentors others. Notably, this happens only after the interviewer asks the follow-up question, “So are you now a user of these tools?”4 In response to this question, Marino describes himself as both a user and teacher of these tools. He mentions a specific class in which he uses and teaches these tools, English 340, a senior-level writing course at University of Southern California. Marino also describes himself as “an evangelist for those tools.” He posits that exposure to what he calls “participatory culture” equates with “wanting to get your friends involved.”

Marino’s narrative casts Marino in the character role of a mentee receiving mentorship from someone else. In an ideal research scenario, we could enrich Marino’s perspective by examining a narrative from Marino’s mentor Jeremy Douglass, in which Douglass narrates the same events from the mentor’s perspective. But in the absence of such a narrative within the DALN, an alternative is to examine another narrative that offers a mentor’s perspective on social-media mentorship. In Patrick Chang’s narrative, which we examine next, Chang describes his use of Twitter in terms that position him as a social-media mentor. By considering how Chang’s description of mentorship intersects and departs from Marino’s, we can build a better picture of how mentorship in social-media spaces may function across multiple users and contexts.

NARRATIVE #2: HOW A SOCIAL-MEDIA MENTOR POSITIONS HIMSELF TO AN AUDIENCE

Patrick Chang’s (2010) “My First Tweet” gives us a glimpse into how social-media mentors may go about informing and motivating their mentees. And in the case of Chang’s narrative, the mentee is the members of the viewing audience. Unlike Marino’s narrative, Chang’s narrative does not unfold as a chronological story-world with multiple named characters. Rather, Chang seems to be speaking directly to the camera, or at least to the interviewer who holds the camera. At the end of the narrative, Chang even promises to “keep you in touch about what’s happening as I continue working with it [the social-media platform, Twitter.]”

Thus, one way to analyze Chang’s narrative is to consider how he positions himself in relation to the audience (BPL #2). Within the first twenty seconds of this narrative, Chang begins to position himself to the audience as a confident user of social media to connect with students and push the boundaries of writing pedagogy (see Video 5 below). For example, early in the narrative, Chang states that “I’m gonna talk about my experiences with Twitter.” He then says that he’s “always interested in how to better communicate with students.” Later in the narrative, he notes particular ways that he uses Twitter with students (as described below). Chang also describes Twitter “as a form of writing” and states that “The challenge [when using Twitter] is you’ve got 140 characters to write something with.”

Interestingly, within the narrative, Chang does not explicitly describe himself as a teacher or scholar. He does, however, position himself as someone who is conscious of national debates about composition pedagogy and how social media might fit positively into writing pedagogy (see Video 6 below). For starters, he frames Twitter early in his narrative as a writing tool, saying that he starting using it “in January, as a form of writing.” Chang also defends social media as a means for teaching and connecting with students. He states that, “I know several writing professors have expressed concern, nationally, about, “Is the quality of writing of students going to go down as a result of this [Twitter]?’” Chang then mentions a “recent Chronicle of Higher Education” article that “indicated that… programs such as Twitter are forcing students to think more concisely, to write more… precisely” (see Video 6 below). By sharing these details with the audience, Chang shows the audience that he is informed about debates surrounding composition pedagogy and still thinks Twitter has potential for use in educational contexts.

In this regard, Chang is arguably positioning himself as a mentor of social media to and for his audience. Like Jeremy Douglass in Mark Marino’s narrative, Chang is showing his mentees (that’s us, the viewers) a social-media technology that he has embraced, then helping us understand how it might be used and how it might fit into scholarly work. For example, Chang describes how “someone is using Twitter to release daily recipes” that are entirely included within the space of one Tweet (140 text characters). Later in his narrative, Chang provides an example of how he uses Twitter with students: to survey students about “the new housing policy” on campus. Chang states that the “response was pretty good,” and he received responses from both current students and alumni (see Video clip 7). These moments help us fill in the gaps of what someone like Jeremy Douglass might say to someone like Mark Marino. In other words, by talking to his DALN narrative’s audience, Chang is giving us one example of how social-media mentors engage with their mentees. He models particular attitudes and behaviors, and he informs the mentees about particular topics.

Narrative #2 and the Four Traits of Social-Media Mentorship

How, then, does Chang’s narrative speak to the four traits of mentorship proposed in this article? If we construe Chang as attempting to mentor or inform his audience, these findings emerge:

- The mentor and mentee share an intellectual or practical goal: Chang positions himself as someone who is interested in writing, effective practices for teaching writing to students, and using social-media writing spaces to connect with students. For viewers who are interested in writing pedagogy, Chang has thus positioned himself as sharing a key intellectual and practical goal.

- The mentor seems willing to maintain the mentorship relationship over time: When Chang makes his final promise to “keep you in touch about what’s happening as I continue working with it,” Chang is suggesting that he is willing to continue sharing insights about Twitter and social media in the future. This remark positions Chang as someone who is willing to continue a mentorship relationship over time.

- The mentor encourages meaningful choice among multiple technologies that may suit the task at hand: Although this narrative focuses primarily on Twitter, Chang does mention Facebook—another social-media tool—at two points in the narrative. At those moments, Chang’s descriptions of Facebook seem to mirror or complement his comments about Twitter, implying that they are sometimes both suitable for the task at hand. For example, when describing why he began using Twitter, Chang states that he became “especially interested… when Twitter hooked up with Facebook.” By this phrase, Chang is likely referring to a Twitter feature that can connect a Twitter account and a Facebook account. When these accounts are connected, texts submitted to Twitter are automatically posted to the connected Facebook account. In short, Chang’s initial interest in Twitter seems premised on a possible connection or common task utility between Twitter and Facebook. Chang makes one other reference to Facebook, and although it is brief, this reference also implies that Facebook and Twitter are both tools that can be used for a particular task at hand. Chang comments, “I’m amazed at how many people track stuff on Facebook, uh, with just quick thoughts that you have about stuff.” This has similarities with Chang’s description of Twitter, in which he emphasizes the challenge of communicating “concisely” and “precisely” in “140 characters.” In this way, Chang models the mentor behavior of considering multiple tools that may be suitable for a task at hand.

- The mentee perceives the mentor as being proficient with the technology at hand: Throughout the narrative, Chang positions himself to the audience as a competent Twitter user who has acclimated to the platform in a fairly short time span. He claims to have joined Twitter “in January.” Because Chang’s narrative was recorded and submitted in April 2010, we can infer that Chang may have been using Twitter for approximately four to five months at the time he submitted his DALN narrative. In that short span of time, Chang positions his character in the narrative as moving from sending his first tweet to using Twitter to communicate with students.

So far, we’ve examined a narrative in which the narrator positions himself as a mentee and another where the narrator positions himself as a mentor. In the sample set’s third narrative, dual narrators Daisy Pignetti and Cynthia Cochran (2009) position themselves as mentors and mentees at the same time. This dual positioning of mentor-mentee complicates our understanding of how mentor-mentees position themselves, and how those roles may manifest in classroom practice.

NARRATIVE #3: WHEN LINES BETWEEN MENTOR AND MENTEE BLUR

In “Twitter, Facebook, Families, and Students,” we see narrators who position themselves as both mentoring other people in social-media spaces and being mentored by others. Consequently, this narrative represents a more fluid and complex model of mentorship in social-media environments, in which a single individual can have relative expertise and mentorship relationships for different social-media tools and different scholarly projects or goals. This narrative also gives us a peek into how social-media mentorship can occur in multiple domains of one’s life, including personal or recreational use of social media.

Pignetti and Cochran position themselves to the audience (BLP #2) as both teacher-scholars and family members. Early in the narrative, we learn that Pignetti and Cochran are in-laws (related by marriage). They smile and laugh throughout the narrative, and they seem pleased to be together on camera. But they also position themselves as teachers who think critically about how social media affects their students’ experiences inside and outside the classroom (see Video 8 below). For example, Pignetti mentions that the pair are both attending the 2009 Conference on College Composition and Communication, and they bumped into each other when Cochran attended Pignetti’s session “about Twitter.” We learn that Cochran, too, is interested in social media: she is hoping to study Facebook and family relations for an upcoming scholarly project. So both narrators position themselves to the audience as scholars with opinions on how social media operates in the classroom and in other literacy contexts.

Pignetti and Cochran also position themselves in relation to each other, as co-narrators and characters in the narrative (BPL #1). Pignetti positions herself as a scholarly user of Twitter, stating that she that she “talked about Twitter” in her conference presentation. Pignetti also positions herself as someone who mentors her students in their use of Twitter and other social-media tools. Pignetti suggests that her students don’t always think critically about social media, saying that “teaching Twitter I think helps the students’ digital literacy, because even though we assume that they’re natives, they really aren’t.” She further comments that her students “will use Facebook, but when you ask them to go beyond, it’s like ‘Why are we doing this and what are we doing?’” Pignetti seems to view Twitter as a tool for helping to overcome this uncritical use of technology, saying that her “literacy of my students” as being “greatly enhanced by greatly enhanced by having them post on Twitter, and then me also emulating the practice for them” (see Video 9 below).

Yet although Pignetti is positioning herself as a social-media mentor in relation to her students (BPL #1), she also positions herself as having received mentorship from other scholars on Twitter. When someone behind the camera asks, “How did you learn to tweet?,” Pignetti says, “I think I just started following a lot of the people [on Twitter] that I know who are techy like Howard Rheingold, and all these people who I really like their work.” As Pignetti continues speaking, Pignetti positions Rheingold as a fellow character (BLP #2) in ways that make him sound like social-media mentor. For example, Pignetti states that “now I have Howard commenting on my blog,” which implies that Pignetti used Twitter to draw Rheingold’s attention to her blog. Pignetti also states that she followed Rheingold’s “whole thing about laptop campuses” with interest. Pignetti teaches on what she calls a “laptop campus,” and she states that student attention is “something that I’ve started to look at with my own teaching.” In that regard, Pignetti and Rheingold seem to share a common intellectual project or goal, even if they are not directly collaborating toward that project or goal.

Thus, in the space of just a few sentences, Pignetti gives us a model for seeing a fellow social-media user as a form of mentor. It’s not clear if Pignetti and Rheingold are colleagues outside the context of Twitter. But within the world of Twitter usage, Pignetti points to Rheingold as displaying this chapter’s four proposed traits of social-media mentorship:

- Common goals: As described by Pignetti, the pair share a common intellectual interest in student attention on laptop campuses.

- Relationship over time: Pignetti also describes having multiple interactions or “touch points” with Rheingold through Twitter over time.

- Multiple tools for the task at hand: We might say that Rheingold’s skepticism about student attention on laptop campuses mirrors Pignetti’s skepticism about her students’ attention on a laptop campus. In that regard, they may both be questioning the suitability of laptops as a classroom learning tool.

- Perceives mentor as technically proficient: Pignetti describes Rheingold as seeming “techy,” which may speak to Pignetti’s perception of Rheingold’s technological proficiency.

What we can say, from Pignetti and Cochran’s narrative, is that displaying the traits of a social-media mentor does not always correlate with positioning oneself as a confident teacher-scholar of social media. For example, when Cochran positions herself in relation to Pignetti, Cochran suggests that she’s not as experienced with Twitter or social media as Pignetti. She states that “I have a Master’s degree in Computer Applications to Instruction, but I’m so behind the times now that I have to learn from my husband’s wife [Pignetti]” (see Video 9 above). When asked by the interviewee if she teaches with Twitter, Cochran positions herself as a relative novice: “I’ve only tweeted like 3 times on there and I haven’t really figured out what to do.” Interestingly, Cochran does state that she joined Twitter “because of an alum of mine,” which may refer to one of Cochran’s former students. But it sounds like the alum did not serve as an ongoing mentor over time because Cochran still hasn’t “figured out” Twitter.

But despite this attempt to position herself to the audience as behind the times, other elements of this narrative contradict Cochran’s positioning of herself as a social-media novice. For example, when Pignetti positions Cochran as a fellow character, she suggests that Cochran is just as engaged as Pignetti with social media’s relevance to their scholarly field, but in different ways. For example, Pignetti mentions that Cochran “wants to do a project on families of Facebook” and suggests that the pair had a “conversation” about Cochran’s scholarly project after Pignetti’s conference session. And when Cochran talks about her teaching, she makes connections between her students’ web-design preferences and their fondness for Facebook, a social media tool:

But I do blog a little bit, and I have my students develop webpages. But what’s interesting about them is that they are very Facebook literate, when it comes to designing their own webpage, that has changed the way they design them. So now they want them all to look like Facebook pages. And I don’t have to actually teach as much about design as, they’re like “I want 3 columns”… Isn’t that interesting? (See Video 11 below)

So although Cochran may not teach “with” Facebook or Twitter, she reflects awareness of how social media affects students’ methods of tackling an intellectual project (designing a web page) and how their outside-of-classroom literacies interact with the literacies that Cochran teaches. We learn elsewhere in the narrative that Cochran is also an active Facebook user herself, having used Facebook to learn the location and time of Pignetti’s conference session, as well as using it to communicate with other family members. In this regard, Cochran may be a useful model for teachers who do not currently use social media in the classroom but hope to provide social-media mentorship to their students. Cochran reflects a critical awareness of how social media intersects with her students’ classroom literacy practices, and ways to engage with social media as a discourse, regardless of whether one uses that social-media tool in the classroom.

Finally, we might note that when Pignetti and Cochran position their students as characters in the narrative, they do so in terms of their different campus contexts. These narrative moves remind us that local and institutional contexts play a role in how students and teachers use technologies in the classroom. As mentioned above, Pignetti teaches on a “laptop campus” where students “are given this machine and they want to play with it but they don’t really think about what they’re doing” (see Video 11 above). Cochran states that her campus is “not a commuter campus; we’re a four year campus, so the students are kind of against the idea of using technology too much because they’re like ‘We’re sitting right here.’” These narrative moments remind us to think broadly about how contextual factors affect our use of social media in the classroom. Campus and classroom contexts are one group of possible factors, but as this narrative suggests, non-scholarly uses of social media and hardware access (or non-access) can also impact social-media use.

Narrative #3 and the Four Traits of Social-Media Mentorship

This third narrative enriches our understanding of the four proposed traits by showing us a fluid model of social-media expertise. Rather than a mentor who seems to be uber-competent with many social media tools (Jeremy Douglass), or a mentor who seems exceptionally competent with one social-media tool (Patrick Chang), we view a set of mentors who have relative expertise with different social-media tools and use them very differently to connect with students and scholarship.

Here are some of the ways that Pignetti and Cochran’s narrative illuminate this chapter’s four proposed traits of social-media mentorship:

- The mentor and mentee share an intellectual or practical goal: In this narrative, Pignetti and Cochran suggest that even a temporary alignment of goals can help to form a mentor-mentee relationship. For example, Pignetti describes having multiple small touchpoints on Twitter with Howard Rheingold, aligning the pair temporarily on a variety of topics over time. Pignetti’s representation of Rheingold suggests that mentorship need not always be a formalized relationship nor even a relationship that both mentor and mentee acknowledge; she seems to position Rheingold as a mentee independently of whether Rheingold considers himself Pignetti’s mentor.

- The mentor seems willing to maintain the mentorship relationship over time: This narrative calls into question whether mentorship “over time” necessarily implies mentorship over “a long time” or even mentorship on a sustainable or continuing basis. For example, Pignetti seems to be describing Rheingold as a mentor even though the pair have only small flashes of interaction over time, through Twitter. Further research might investigate whether and how “relationship over time” functions in social-media mentorship. That seems especially important given the dynamics of most classrooms, where the realities of semester lengths, class lengths, and direct-instructor interaction time may limit support relationships over time.

- The mentor encourages meaningful choice among multiple technologies that may suit the task at hand: Cochran’s comments about her students’ design preferences suggest that in addition to mentoring students by using social media with them, teacher-scholars may play a role in helping students think about social media and its role in their multiple literacy acquisitions. In other words, perhaps “meaningful choice” means more than selecting a particular tool that suits the task at hand; perhaps “meaningful choice” also implies a critical awareness of how one’s other literacies, including ones other literacies related to social media, affect one’s literacy practices in other domains.

- The mentee perceives the mentor as being proficient with the technology at hand: Again, Cochran’s character positioning may complicate this trait. Although Pignetti states that using Twitter “with” students has enhanced her teaching, Cochran does not say that she uses social media with her students. Instead, she uses her knowledge of Facebook’s interface (which she uses for personal/family reasons) to infer Facebook’s influence on her students’ design preferences. The open question, then, is whether Cochran’s ability to connect students’ design preferences to Facebook has any effect on students’ design choices or their use of social media. In other words, Cochran’s story encourages us to consider the boundaries of social-media mentorship and so-called “perception of proficiency.” There are no clear answers within the narrative, but it would be an ideal topic for further research.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING

Despite being a small set—just three narratives, submitted by a total of four narrators—this data set yields rich potential implications for teaching. The trick is unspooling these complex, culturally situated, and very particular narratives into generalizable conclusions.

To begin to untangle that knot, I use the section below to tie these three narratives together, weaving them as three strands among the study’s four traits of social-media mentorship. Marino’s narrative of himself as a mentee, Chang’s narrative of himself as a mentor, and Pignetti and Cochran’s interwoven narrative of themselves as mentors and mentees serve as useful, non-abstract illustrations for the pedagogical suggestions below. I structure that discussion by considering each of this study’s four proposed traits of social-media mentorship, in turn. By doing so, I hope to encourage readers to examine how these dynamics of mentorship impact their current teaching and how these mentorship practices might influence future teaching practices.

Implementing Mentorship Trait 1: Work to help students connect a particular intellectual or practical goal to a particular social-media tool. In all three narratives, the mentor-mentees shared a clearly articulated intellectual or practical goal. Once that goal had been agreed upon and understood, social media could provide a gateway for forwarding the intellectual or practical goal.

So in the classroom, perhaps social-media mentorship begins by helping students articulate a goal and identify associated tasks. Then, students and teachers can work together to identify tools that may suit the tasks at hand. To take Pignetti’s example, students interested in particular issues could be encouraged to use social media to connect with thought leaders on those topics. Or to take Mark Marino’s example, suppose students are working on a collaborative project in which they are researching similar topics. In that case, an associated task might be “to share online sources that may be useful to multiple students pursuing similar research topics.” With that task in mind, it becomes possible to consider possible tools. Those might include a social bookmarking tool like de.li.cious or Diigo, but many other social-media tools have the ability to bookmark and share sources. Pinterest, for example, provides an interface for visual bookmarking. A hashtag on Twitter might provide a means for organizing bookmarks. And certainly, there are many other examples.

Suggestions for implementing Mentorship Trait #1:

- Discuss intellectual or practical goals with students. These might be goals that you have set as the teacher, in which case you might discuss the goals with students. Alternately, encourage students to articulate intellectual or practical goals.

- Identify particular tasks that would serve the intellectual goal. This prepares you to select social-media tools that may support the goal.

Implementing Mentorship Trait 2: Position yourself as providing ongoing support to students over time. Almost by definition, teachers are in the business of providing ongoing support across the length of a course. But this study suggests that when it comes to social-media mentorship, the mentee’s perception of the mentor’s willingness to support them might have more influence than the amount of time or effort exerted on support. Marino, for example, suggests that he and Douglass continue to use social-media tools to coordinate their project over time. Chang promises to keep us updated at the end of his narrative, but based on my searching in the DALN, Chang does not actually return to the DALN to submit an update.

Suggestions for implementing Mentorship Trait #2:

- When introducing a new technology in the classroom, emphasize that students are not expected to master this technology in a short period of time.

- Provide ongoing opportunities for students to ask questions about the technology, including questions about how the technology fits into your shared intellectual project or goals.

- Encourage students to engage with the technology over time.

Implementing Mentorship Trait 3: When choosing a social-media tool, consider multiple options that may suit the task at hand. All three narratives include examples of mentors framing their tools in terms of possible alternatives. Even in Chang’s narrative, which focuses only on Twitter, Chang frames Twitter in terms of how it compares and contrasts with other tools for “sharing quick thoughts and ideas.” If we construe “sharing quick thoughts and ideas” as an intellectual goal, then Chang’s narrative does not just encourage us to use Twitter—it also encourages us to consider available options.

Suggestions for implementing Mentorship Trait #3:

- Consider multiple tools for a particular task at hand. Resources like Brian Solis’s (2016) “Conversation Prism,” which breaks the social-media world into categories by function or theme, may be helpful. You might also use Web search engine queries like “alternative to [tool name here]” to identify other possibilities.

- Consider asking your students to help you brainstorm possible tools. As you do so, encourage students to consider both the ways that they already use social-media tools and new ways that they might use them.

- Consider the access implications of implementing social-media tools. Each social-media tool differs in its interface, its level of accessibility for users with various needs, and the hardware and Internet access required for each. For example, it would be difficult to use the photo-sharing network Instagram without sufficient access to handheld devices with built-in cameras (smartphones, tablets, etc.).

- Be open-minded to the possibility that social-media tools may serve the task at hand, but consider them in light of non-social-media alternatives.

Implementing Mentorship Trait 4: Consider that demonstrating “proficiency with the technology at hand” may have more to do with curiousity and willingness than functional literacy with technologies. For teachers who are intimidated by new technologies, the prospect of demonstrating “proficiency with the technology at hand” may be frightening. But in the three narratives from this study, proficiency was not just a matter of seeming “good” at using the technology. It was also reflected in a willingness to try new things, learn as you go, and commit to an intellectual goal. Pignetti, for example, describes her early days on Twitter as simply following other “techy” people. From this statement, we might infer that Pignetti spent time just watching the Twitter world go by, observing how users like Howard Rheingold leveraged the platform. Similarly, Cochran does not use Facebook in the classroom, but she is intellectually curious about how Facebook use outside the classroom influences students’ understanding of the platform.

Suggestions for implementing Mentorship Trait #4:

- Position yourself with students as someone who is open-minded to trying something new.

- Find a mentor or other help resources to help you acclimate to using a particular social-media tool in particular ways. If you cannot find a mentor among your friends or colleagues, consider following Pignetti’s example of learning by observing the behavior of other users.

- Consider starting small. For example, perhaps you ask students to simply observe behavior on a social-media tool rather than actively participate. In many cases, students can engage with the rhetoric of social media without even creating a user account on a particular platform.

- If you prefer, practice using a particular social-media tool well before you integrate it into your curriculum. When you feel more confident, you can integrate it into your curriculum.

Adoption of this Study’s Methods and Future Research Directions

In addition to the suggestions above, I sincerely hope that readers will consider using this study’s methods to continue exploring dimensions of technological literacy. Most directly, I invite teachers and students to make their own literacy narratives about mentorship, social media, and literacy uptake. Then teachers and students might consider analyzing those narratives using positioning theory and literacy sponsorship. This, in its own way, would be a form of further research that builds on this study.

One way to expand on this study might be to examine the same topic—social-media mentorship—but with a larger and more intentional data set. This study analyzes just three literacy narratives with a total of four narrators. Possibly, the four proposed traits of social-media mentorship may not generalize to other mentor-mentee situations. Further research could enrich this data set and nuance this study’s understanding of the four proposed traits of social-media mentorship. By comparing this list to the narratives and experiences of others, we might deepen our understanding of how human relationships affect the uptake of new tools for learning and scholarship. I also hope that readers of this chapter will consider sharing in this investigation by reflecting on how the four traits compare to their own experiences—and perhaps sharing their own literacy narratives on that topic to the DALN.

Another way to expand this study would be to gather or analyze narratives in which students serve as mentors to teacher-scholars. Although teacher-scholars do serve as mentors to their students, the dynamic can also work the other way around: students can serve as mentors to teachers. For example, in Frost (2011), it was Frost’s own students who chose to use Facebook to support their research for Frost’s composition class. In that situation, Frost was mentored by her students, absorbing new ways to use social media to forward the goals in a composition classroom. Further research might investigate how and whether students enact the role of mentor to their fellow students and to teacher-scholars. We might also investigate whether the four traits of social-media mentorship apply to students mentoring each other or students mentoring the teacher-scholars around them.

This research might also benefit from the integration of other research methods. As described above, studying narrative has affordances, but it also has limitations. Further research might use ethnography or interview protocols to learn more about how mentor-mentee relationships function within the lives of teacher-scholars and their students.

Finally, for scholars who wish to use Bamberg’s three-tiered model of positioning theory to analyze other types of literacy or other target populations, the DALN makes it fairly easy to find narrators who are choosing to position themselves in relation to particular literacies, cultural events, or other demographics that may be interesting to researchers. The DALN’s open metadata policy means that people submitting narratives are prompted—but not required—to add a range of descriptive metadata to their narrative’s archive. Narrators must title their DALN archive, but all other metadata is optional. Narratives are given the option to enter data about the archive’s author (name, gender, race, year of birth, etc.) and information about the narrative (description, keywords, decades covered, geographic information, etc.). Each optional feature includes an open text box, so archive authors may enter whichever terms or data they prefer. So for researchers who are prepared to put the DALN search engine to work, the DALN presents many possible opportunities to examine narratives by many groups, including but not limited to teacher-scholars.

NOTES

1. Although I had a

particular goal in mind when I searched the DALN, namely finding

teacher narratives that relate to social media, the DALN includes

many teacher narratives that might be mined for other topics

related to teaching practices. For example, at the time of this

writing, there are 451 narratives in the DALN tagged with a

keyword with the word stem cccc. That keyword stem designates

keywords that DALN volunteers manually added to narratives

collected at the annual Conference on College Composition and

Communication (CCCC). Since that conference is primarily attended

by teacher-scholars of rhetoric and composition, many of those 451

narratives were likely submitted by teacher-scholars. Beyond this

individual keyword, there are additional narratives submitted by

teacher-scholars in collections like African-American Women

Professors and Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Professors. There are also

narratives by composition teacher-scholars throughout the DALN,

tagged with varying types of metadata related to terms like

teacher, professor , and so forth. ↵

2. The DALN’s search

engine construes the term social media to mean “any result that

includes the word social or the word media.” Thus, my initial

search for the term social media yielded a total of 179 results.

As I began reviewing those 179 narratives, I soon realized what

was happening. At that point, I returned to the DALN search page

and searched for “social media” in quotation marks. ↵

3. Terminology

note: a single DALN “archive” can sometimes hold multiple files

and/or literacy narratives in one archive. In the case of my three

chosen archives, all three archives included one narrative per

archive. But since that is not universally true across the DALN, I

use the term “archive” to describe my search results here. ↵

4. In the

interest of full disclosure, that interviewee was me. However,

this interview was not in solicited for this research, which I

began nearly a year after assisting with this narrative. In truth,

I had forgotten about this narrative until I began this research

12 months later. And even then, I re-encountered it only upon

searching the DALN for narratives related to the keyword “social

media.” ↵

REFERENCES

Balzhiser, D., Polk, J. D., Grover, M., Lauer, E., McNeely, S., & Zmikly, J. (2011). The Facebook papers. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 16(1). Retrieved from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/16.1/praxis/balzhiser-et-al/index.html

Bamberg, M. G. W. (1997). Positioning between structure and performance. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 7(1/4), 335–342.

Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanič, R. (2000). Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context. New York: Psychology Press.

Berry, P. W., Hawisher, G. E., & Selfe, C. L. (2012). Transnational literate lives in digital times. Logan, Utah: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press .

Bowen, L. M. (2011). Resisting age bias in digital literacy research. College Composition and Communication, 62(4), 586–607.

Brandt, D. (1998). Sponsors of Literacy. College Composition and Communication, 49(2), 165–185. http://doi.org/10.2307/358929.

Brandt, D. (2001). Literacy in American lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brandt, D. & Clinton, K. (2002). Limits of the local: Expanding perspectives on literacy as a social practice. Journal of Literacy Research, 34(3), 337–356. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3403_4

Briggs, T. (2013). Writing a professional life on Facebook. Kairos:

A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 17(2).

Retrieved from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/17.2/

Brodkey, L. (1994). Writing on the bias. College English, 56(5), 527–547.

Bryson, K. (2012). The literacy myth in the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Computers and Composition, 29(3), 254–268. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2012.06.001

Buck, A. (2012). Examining digital literacy practices on social network sites. Research in the Teaching of English, 47(1), 9–38.

Buck, A. M., & Hawisher, G. E. (2013). Mapping literate lives: Narratives, languages and histories. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Carter, S. (2009). The way literacy lives: Rhetorical dexterity and basic writing instruction. New York: SUNY Press.

Chang, P. (2010). My first tweet. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/0105de74-872a-44d0-9ad7-0a5cfa17806b

Childs, E. (2015). Using Facebook as a Teaching tool. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 12(1). Retrieved from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/praxis/tiki-index.php?page=Facebook_for_Teaching.

Ching, K. L. & Ching, C. C. (2012). Past is prologue: Teachers composing narratives about digital literacy. Computers and Composition, 29(3), 205–220. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2012.05.001

Coad, D. (2013). Developing critical literacy and critical

thinking through Facebook. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric,

Technology, and Pedagogy, 18(1). Retrieved from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/praxis/tiki-index.php?page=Developing_Critical_

Critel, G. (2013). Remixing the digital divide: Minority women’s digital literacy practices in academic spaces. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Dadurka, D. & Pigg, S. (2011). Mapping complex terrains: Bridging social media and community literacies. Community Literacy Journal, 6(1), 7–22.

Davies, B. & Harré, R. (1998). Positioning and personhood. In R. Harré & L. Van Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning Theory: Moral Contexts of Intentional Action (1st ed.), (pp. 32-52). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Davis, O. & Marsh, B. (2012). Networking, storytelling and knowledge production in first-year writing. Computers and Composition, 29(2), 175–184. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2012.03.002

DeVoss, D. N. & Porter, J. E. (2006). Why Napster matters to writing: Filesharing as a new ethic of digital delivery. Computers and Composition, 23(2), 178–210. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2006.02.001

DeWitt, S. L. (2013). Optimistic reciprocities: The literacy narratives of first-year writing students. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

DeWitt, S. L., Selfe, C. L., & Ulman, H. L. (2011). Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Dubisar, A. M. & Palmeri, J. (2010). Palin/Pathos/Peter Griffin: Political video remix and composition pedagogy. Computers and Composition, 27(2), 77–93. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2010.03.004

Elbow, P. (1973). Writing without teachers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frost, A. & Blum Malley, S. (2013). Multilingual literacy andscapes. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Frost, E. A. (2011). Why teachers must learn: Student innovation as a driving factor in the future of the Web. Computers and Composition, 28(4), 269–275. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2011.10.002

Gerben, C. (2009). Putting 2.0 and two together: What Web 2.0 can teach composition about collaborative learning. Computers and Composition Online. Retrieved from http://candcblog.org/Gerben/

Hamilton, H. E. (2005). Epilogue: The prism, the soliloquy, the couch, and the dance—The evolving study of language and Alzheimer’s disease. In B. Davis (Ed.), Alzheimer Talk, Text and Context (pp. 224–246). New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Harré, R. & van Langenhove, L. (1998). Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action (1st ed.). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hawisher, G. & Selfe, C. L. (2004). Literate lives in the information age: Narratives of literacy from the United States (1st ed.). Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hollway, W. (1984). Gender difference and the production of subjectivity. In J. Henriques, W. Hollway, C. Venn, & Walkerdine, V. (Eds.), Changing the Subject (pp. 227–263). London: Methuen.

Kaufer, D., Gunawardena, A., Tan, A., & Cheek, A. (2011). Bringing social media to the writing classroom: Classroom salon. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 25(3), 299–321. http://doi.org/10.1177/1050651911400703

Kirtley, S. (2012). Rendering technology visible: The technological literacy narrative. Computers and Composition, 29(3), 191–204. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2012.06.003

Lawrence, A. M. (2015). Literacy narratives as sponsors of literacy: Past contributions and new directions for literacy-sponsorship research. Curriculum Inquiry, 45(3), 304–329. http://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2015.1031058

Pignetti, D. & Cochran, C. (2009). Twitter, Facebook, families, and students. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/379914d5-4e81-4c2b-adfb-a00a8999331c

Potts, L. & Jones, D. (2011). Contextualizing Experiences: Tracing the Relationships Between People and Technologies in the Social Web. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 25(3), 338–358.

Maranto, G. & Barton, M. (2010). Paradox and promise: MySpace, Facebook, and the sociopolitics of social networking in the writing classroom. Computers and Composition, 27(1), 36–47. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2009.11.003

Marino, M. C. (2010). The birth of writer response theory (.org). Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/2a492736-6ec8-46b0-b9b4-6b419ad4edd3

McClure, R. (2014). It’s not 2.0 late: What late adopters need to know about teaching research skills to writers of multimodal texts. The Writing Instructor. Retrieved from http://parlormultimedia.com/twitest/mcclure-2014-03.

Moxley, J. & Meehan, R. (2007). Collaboration, literacy, uthorship: Using social networking tools to engage the wisdom of teachers. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 12(1). Retrieved from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/12.1/binder.html?praxis/moxley_meehan/index.html

Pennell, M. (2007). “If Knowledge Is Power, You’re about to Become Very Powerful”: Literacy and Labor Market Intermediaries in Postindustrial America. College Composition and Communication, 58(3), 345–384. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20456951.

Purdy, J. P. (2010). The Changing Space of Research: Web 2.0 and the Integration of Research and Writing Environments. Computers and Composition, 27(1), 48–58. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2009.12.001.

Reid, L. (2015). Returning Adults in the Multimodal Classroom. Showcasing

the Best of CIWIC/DMAC Approaches to Teaching and Learning in

Digital Environments, 1st edition. Retrieved from http://www.dmacinstitute.com/showcase/issues/