The Archive as Intervention for Teaching Reflection

LILIAN W. MINA

ABSTRACT

This chapter examines how literacy narratives from the DALN develop international multilingual writers’ reflective writing skills. Building on Dewey’s (2012) conceptualization of reflection as a habit of mind that requires teacher intervention and Yancey’s (1998) use of reflection as a frame for thinking about writing, the chapter employs a mixed-method study that extends Yancey’s framework from reflection on writing to the territory of reflection on life situations. Data from 35 international multilingual writers in a first-year writing course in a U.S. university are analyzed, and findings show the DALN’s potential for teaching reflection. The discussion presents implications for instruction of international multilingual writers as well as DALN material gathering and management.

***

May 2015: Challenge Posited

Scene # 1

|

I sat among a group of instructors of an entry-level writing course designated for international multilingual students to conduct program assessment of the learning outcomes of that course. A strikingly disappointing result of the two-day portfolio assessment was that the majority of students performed poorly at reflective writing tasks and tended to summarize and describe rather than analyze or reflect. That result wasn’t as shocking to me because I had a similar observation in my first-year writing (FYW) classes for international multilingual students. The first writing assignment in FYW classes at Miami University is a reflection on the use of rhetoric in students’ lives. Between struggling with the meaning of rhetoric and recalling an appropriate situation to write about, the reflection component of the assignment makes a shy, if any, appearance in students’ narratives. The recurrence of that problem made me think of designing tailored instruction in order to help multilingual students recognize the elements of reflection in texts without risking them imitating the content or style of these texts. This task entailed answering the four challenging questions in Figure 1.

Scene # 2

Still intrigued and puzzled by these challenging questions, I saw the Call for Papers (CFP) for this edited collection. As I was reading the CFP, I stopped at the two questions under the Literacy strand: 1) How do you use the DALN to engage students in literacy studies? and 2) What approaches to the collection seem to foster students’ critical awareness about literacy? (Harker, McCorkle, & Comer, 2015). The words “critical awareness” and “literacy” stood out and made me think about the reflective writing problem again. I particularly thought of David Bloome’s (2013) definition of literacy as “a collection of cognitive and linguistic processes associated with reading and writing” and Sandra Giles’s (2010) definition of reflection as “any activity that asks you to think about your own thinking” (p. 191). When combined, the two views of literacy as a cognitive process and reflection as a metacognitive skill result in a concept of reflective writing as an advanced form of literacy. The question was whether I could address the two questions in the CFP by using literacy narratives from the DALN collection to design that tailored instruction I was pondering to help multilingual students improve their reflective writing skills. Meanwhile, the theme for my fall 2015 FYW classes was the culture of food; from the excerpt in Figure 2, you can see that the narrative assignment was on food and communication, not literacy. Another challenge!

| In this assignment, you will recall

one situation in which food and communication interacted

together. You may write about communication that

happened during a meal, in a restaurant, while preparing

a holiday meal, while watching a TV cooking show, during

a special occasion dinner, or any other communication

related to food. As you describe the situation, you will reflect on it and the rhetorical strategies (evidence, personal experiences, for instance) you have or haven’t used and how using these strategies affected the outcome of the situation. Did you have effective communication in that situation? Why? Why not? Do you think there were other strategies you could have used to have a better outcome? |

David Barton’s (2007) argument that “[u]sing an everyday event as a starting point provides a distinct view of literacy” offered me a lifeline that connected the scattered dots of literacy, reflection, and narrative (p. 4). Within this social framework of literacy, the food-and-communication narratives were a starting point to learn reflective writing, a required and a complex type of literacy that pushes us to rethink “what is involved in reading and writing” (Barton, 2007, p. 4). I decided to take the challenge and Scott’s (1997) recommendation to adapt the literacy narrative assignment for various courses and reasons. My goal was to examine how literacy narratives from the DALN can be used as a form of intervention to teach reflective writing to international multilingual students.

May – August 2015: Challenge Accepted

Reflection has been defined as a metacognitive skill (Donovan, Bransford, & Pellegrino, 2000; Yancey, 1998), and scholarship on reflection in writing studies has focused almost entirely on reflection on writing at different stages in the composing process (e.g., Amicucci, 2011; Giles, 2010; Greene, 2011; Yancey, 1998).

In her landmark work on reflection, Kathleen Yancey (1998) describes reflection as “an analysis of learning” (p. 6). It is the process a student uses to better understand their learning (or lack of) in a writing situation, usually a given writing assignment. Yancey explicates reflection as a frame of thinking deeply about goals, retrospection of these goals (e.g., obstacles, shifting views, changing strategies), and lessons. She identifies three temporal stages in the reflection thinking process: projection of goals to be achieved, retrospection of these goals to review whether the goals have been achieved, and revision of achieving or failure to achieve the goals and the lessons learned along the way. Although Yancey’s primary focus was on writing goals, the same stages can be used to reflect on the achievement of any goals. Reflection, as Yancey explains, is a habit of mind and a frame of thinking. Instead of limiting reflective writing to reflection on writing goals and tasks, in this study I extended Yancey’s framework to reflection on any life situation or experience, including the food-and-communication situations students wrote about in their first assignment.

This extension ofYancey’s framework makes reflective writing more inclusive of a wider range of reading and writing assignments and activities that require students to think deeply and critically. Holly Lawrence (2013) captures these activities in her conceptualization of reflective writing as “writing exercises and assignments that are self-reflective, self-referential, or self-expressive in nature… exercises that ask the writer to write about herself or himself” (p. 193). Jerome Bruner (2004) brings this argument to narrative writing when he contends that the telling of these stories “achieves the power to structure perceptual experiences, to organize memory, to segment and purpose-build the very ‘events’ of a life” (p. 694). Therefore, the food-and-communication narrative I asked international multilingual students to write was a reflective writing assignment that required students to restructure their perception of their lived experiences as these experiences became segments for reflection. Moreover, reading, analyzing, and discussing two literacy narratives from the DALN archive was a reflection activity and a literacy event, or “an activity which involves the written word” (Barton, 2007, p. 35).

Understanding literacy means trying to understand the “particular” events that involve reading and writing (Barton, 2007, p. 36). Barton argues that “[u]sing an everyday event as a starting point provides a distinct view of literacy” (p. 4). Deborah Brandt (2001) further argues that reading and writing are contextual and usually embedded in other activities that “give reading and writing their purpose” (p. 3). Integrating the reading and discussion of two literacy narratives from the DALN within the social context of writing and revising those narratives weaves reflection and literacy in a delicate but solid tapestry, thus enriching and expanding our very definition of literacy in writing studies to include more than reading and writing. This new and extended definition is suitable for the purpose of this study that examined the possible effect of reading literacy narratives on multilinguals’ reflective writing.

Janet Eldred and Peter Mortensen (1992) define literacy narratives as “those stories… that foreground issues of language acquisition and literacy” and “include explicit images of schooling and teaching” (p. 513). Two decades later, Sally Chandler (2013) adds reflection to literacy narratives and defined them as “reflective stories about experiences with reading and writing” (p. 2). Susan DeRosa (2002) strongly argues for literacy narratives as a form of reflective writing in which students address questions about their past literacy experiences. Furthermore, Cynthia L. Selfe and the DALN consortium (2013) expand these conceptions to include all narratives and affix reflection at the core of narrative writing. They argue that narratives are almost always laden with self-interpretation and self-reflection on the narrated event as narrative writers use their narratives as sites of redefining themselves and the events they narrate, “formulat[ing] their own sense of self.” These definitions and utilizations of (literacy) narratives illustrate both the temporal and topical element of reflection Yancey (1998) describes in her discussion of reflective writing.

Scott’s (1997) argument that teacher “guidance” and “intervention” in the narrative writing process can transform students’ basically descriptive narratives into more “reflection and critical interrogation” (p. 115) points out the teacher’s role throughout students’ reflection process beyond asking the right initial questions that will stimulate reflection (Yancey, 1998). In his discussion of reflection as a habit of mind, Dewey (2012) clarified that role by arguing that the teacher’s responsibility is to prepare the suitable environment that “will arouse serviceable mental responses” and eventually develop this mental habit through training and intervention (p. 187). He theorized intervention as an art of teaching. In other words, using intervention materials to design tailored instruction that would help students understand, develop, and practice reflection is a desirable act on the condition of selecting the appropriate intervention materials.

Scholars have cautioned against using published authors’ narratives as models because such polished writing may “marginalize student writing” (Scott, 1997, p. 114). Moreover, Caleb Corkery (2005) discourages the use of highly polished literacy narratives in classes where students may “already feel outside” because of their shaky confidence in their literacy skills as, I argue, is the case with newly arrived international students (p. 49). Corkery is particularly skeptical of the negative influence these narratives may have on students as they can’t identify with those writers or form what he calls “identification bonds” with them (p. 56). Corkery’s concern is that the lack of connection between the readers and writers of these narratives may result in the readers’ tendency to imitate the language, content, and styles of those narrative they read as they aspire to write similar “model” narratives. With these cautions in mind, my decision was to use literacy narratives written by multilingual writers who speak English as an additional language in order to help establish that identification bond between the readers (my students) and writers.

Based on this brief review of scholarship in writing and literacy studies, I transformed the challenging questions I started with into three research questions that I addressed in this quasi-experimental study:

- Does using two literacy narratives from the DALN archive influence the reflective writing of international multilingual students?

- To what degree do the reflection elements of the goal, shifting views, and lesson change in a subsequent draft of a reflective writing assignment?

- How do the statements of the goal, shifting views, and lesson change in a subsequent draft of a reflective writing assignment?

August 2015 Challenge-in-Action

After students turned in the first draft of their food-and-communication narratives and completed peer review, it was time for the intervention. I created a list of questions for students to answer while they read the two literacy narratives from the DALN archive (watch Video 1 for the questions).

I split each class in four groups and handed out copies of the narratives; two groups read each narrative and answered the questions in a Google Doc. After they all finished reading and answering the questions, we started a whole-class discussion of the two narratives, one at a time. At the end of class, I introduced the revision plan task and asked students to follow the prompt (presented in Figure 3), complete it by midnight of the same day, and start revising their food and communication narratives accordingly.

| Towards achieving the goal of

helping you become independent writers/reviewers, it is

important to know how to revise your writing based on

the feedback you receive. This blog post is intended to

help you get started with developing your revision

skills. Because Inquiry I assignment is about reflection, your first task will be to revise your essay for reflection. Use the notes you had from our analysis of two narrative essays in class to help you decide how best to revise your reflection writing in this essay. The first step is to choose TWO other global areas in your essay that need revision. Use 1) the feedback you received from me, your peer, and/or a writing center consultant, 2) the assignment expectations, and 3) the assessment rubric to choose the areas that need most of your attention as you revise your essay. Include a short (3-4 sentences) explanation of how you’re going to revise this area in your essay and how the feedback helped you. A good revision plan has action verbs to specify what needs to be done (add, develop, change, reflect, fix,… and so on). |

August 2015: Challenge-in-Action Continued

Study Design

The purpose of this quasi-experimental study was to examine whether the use of two literacy narratives from the DALN archive (independent variable) would result in any change in students’ reflective writing (dependent variable). Data came from 29 international multilingual students (28 from China and one from Kazakhstan), with their first draft of the food-and-communication narrative as pre-test and the final drafts as post-test. In order to safely attribute any changes seen in final drafts to the intervention and not to other variables (e.g., peer review), I collected students’ revision plans devised after the intervention, as explained above.

Data Analysis

To answer the research questions, I used deductive and inductive data analysis. The deductive approach was built on Yancey’s (1998) theoretical conceptualization of the elements of reflection “projection, retrospection (or review), and revision” (p. 6). The fact that reflective writing in this study was not, as I explained earlier, identical to Yancey’s conceptualization resulted in a number of problems during the deductive analysis. For a start, large portions of the data were left uncoded. Also “revision” didn’t appear in students’ writing, while additional elements were identified. Another problem was that retrospection stood out as a distinct construct from review. The nature of the assignment and the different conceptualization of reflection did not equate retrospection to review. These challenges mandated the use of an inductive approach in order to capture other elements of reflection that emerged from the data. Therefore, I complemented Yancey’s theoretical framework of reflection with an open frame. Not only does this step expand the understanding and conceptualization of reflection in writing studies, it also provides a more accurate analytical procedure needed to comprehensively answer my research questions.

Qualitative Analysis

The next step was to operationally define elements of reflection identified in the data. These definitions emerged naturally from carefully reading the data and closely recording analytical memos with my notes (Hesse-Biber, 2010). I used these preliminary operational definitions to code the first and final drafts of five students (about 17% of the data) and create a detailed coding scheme with possible themes and sub-themes. To ensure the consistency of findings, I asked another researcher to code the same drafts (Creswell, 2014) to calculate the intercoder reliability or “the amount of correlation between two or more raters or coders” (Lauer & Asher, 1988, p. 138). Lauer and Asher argue that clearly articulated operational definitions of constructs should help coders reach agreement easily. I calculated the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient r = 0.86, which is a relatively high reliability (Creswell, 2014; Gall, Gall, & Borg, 2007). Based on the discussion I had with the other researcher, I made minor changes in the operational definitions in order to better capture all the elements of reflection in the data.

Three main categories representing the three elements of reflection emerged: goals, shifting views, and retrospection. Furthermore, I was able to identify seven sub-categories in the data. Below are the operational definitions of all main and sub-categories. Table 3 in Appendix A exhibits examples for each definition from the data.

Goals: what

the writer or the people involved in the narrative wanted to achieve

This category was broken down into three sequential moves:

- Projection of goals: An explicit or implicit statement of the original goals set

- Process of achieving goals: A statement of a step to take or taken towards achieving the projected goal

- Retrospection of goals: A statement of the outcome of the event in the narrative that indicates whether or not the projected goal was achieved

Shifting views: how

the writer’s or other people’s feelings, thoughts, and/or positions

may have changed throughout the event in the narrative

This category was broken down into two temporal views:

- Initial view: A statement of the writer’s and/or the other individuals’ feelings, thoughts, stances at the beginning of the event in the narrative

- Final view: A statement of the writer’s and/or the other individuals’ feelings, thoughts, stances at the conclusion of the event in the narrative, if different from the initial view

Retrospection: the

understanding the writer has developed due to the success or failure

of achieving the goal

This category was broken down into two dialogic ones:

- Lesson: A statement of the lesson the writer has learned from the event narrated.

- Analysis of lesson: A statement of implication,

consequence, significance, reason, interpretation of the lesson.

The next step was to convert these categories and sub-categories into a coding scheme for data analysis. As I was coding all the data, I noticed that some students rephrased their goals and/or lessons for emphasis. I didn’t code statements with iterations of the goal or the lesson to avoid duplication of codes and any possible inconsistency of results.

Quantitative Analysis

These resulting codes became the input for quantitative analysis (Srnka & Koeszegi, 2007). Although quantitative data analysis traditionally requires a large number of participants, I argue that the relatively large amount of verbal data collected in this study made a good foundation for quantitative analysis. Additionally, generalizing to larger populations of students was not my purpose of doing this study, and thus having a larger number of participants was not necessary.

The numerical data came from coding the verbal data before changing these codes into numbers. I later used these numbers to calculate both descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics included the means and standard deviation of each element of reflection in order to measure the change in reflection between students’ first and final drafts. Then, I ran t-test on first drafts (pre-test) and final drafts (post-test) to compare the outcomes (Creswell, 2014) and determine if the change between drafts was statistically significant.

January – May 2016: Challenge Resolved

Elements of Reflection Across Drafts

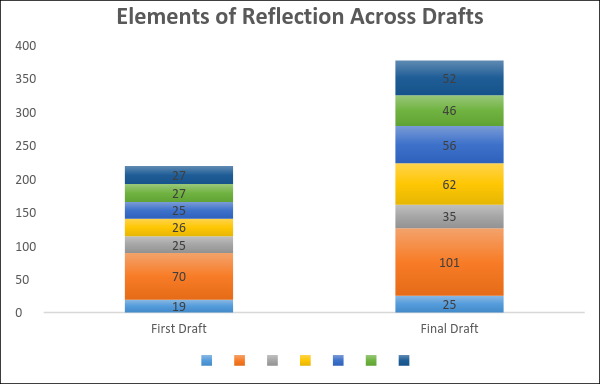

It was easy to notice the increase in the total count of statements representing the three main elements of reflection across students’ first and final drafts, as demonstrated in Figure 4.

In order to account for the amount of change in the elements of reflection across student’s drafts, I ran descriptive statistics to calculate the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of all seven sub-categories of reflection, as demonstrated in Table 1.

| Element of Reflection |

First Draft

(N=29)

|

Final

Draft (N=29) |

||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Goal Projection | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.64 |

| Goal Process | 2.41 | 3.09 | 3.48 | 3.68 |

| Goal Retrospection | 0.86 | 1.16 | 1.21 | 1.54 |

| Initial View | 0.90 | 1.08 | 2.14 | 1.90 |

| Final View | 0.86 | 0,88 | 1.93 | 1.62 |

| Reflection | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.59 | 1.32 |

| Analysis | 0.93 | 1.10 | 1.79 | 1.72 |

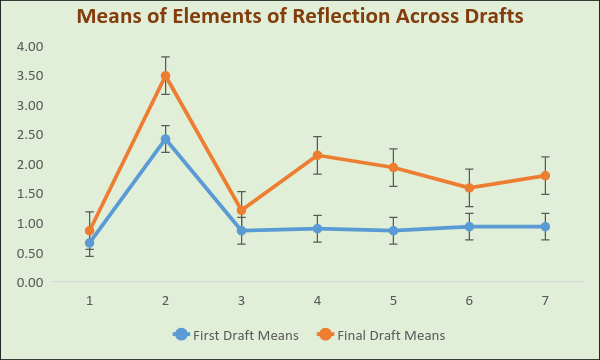

To support my argument that the use of literacy narratives from the DALN has helped improve international multilingual students’ reflective writing skills, it was important to know whether the change in means displayed in Figure 4 was statistically significant in order. To that end, I ran a series of paired two-sample t-tests, the results of which are displayed in Figure 5.

Results of the t-test show that t =5.26 with P <=t of 0.001, which means that the change at all three elements of reflection was statistically significant. However, this t-test aggregated all elements of reflection, and I wanted to understand more about particular changes in students’ reflective writing skills. I believed that students may have developed different degrees of literacy in terms of reflection. In order to have a better understanding of which element(s) may have been better improved, I ran a number of subsequent t-tests, one on each of the main elements of reflection: goals, views, and retrospection. The results, summarized in Table 2 below, are more intriguing.

| Element of Reflection |

t | P |

| Goal | 2.0 | 0.18 |

| Shifting Views | 13.4 | 0.05 |

| Reviews | 7.3 | 0.09 |

These results reveal varying degrees of change in the three elements of reflection and, accordingly, literacy. In the following sections, I discuss these statistical results, illustrating them with qualitative analysis of students’ writing.

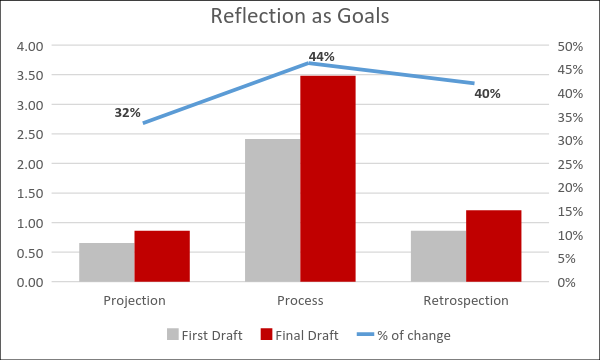

Reflection as Goals

As you can see in Table 2, the change in reflection as goals was not statistically significant, even though students added more details about goals, the process of achieving them, and whether or not they had been achieved, as displayed in Figure 6. Students didn’t seem to have much to add to the statements of the goals they had set in their narratives or the outcome of the event they narrated; they either succeeded or failed to achieve their previously set goals. It is worth mentioning here that life situations—unlike writing assignments, the context of reflection in Yancey’s (1998) work, which have specific goals to achieve—don’t necessarily involve goals. In literacy narratives, writers usually describe the obstacles to achieving a literacy goal, which is again different from everyday life situations like the ones students wrote about in this assignment. This could be one reason why many students didn’t include statements about goals, even after the intervention.

When I looked more closely into students’ drafts, I realized that the 32% change in goal projection occurred mainly because students who didn’t include a statement of the projection of their goals in the first draft (n=6) added those statements in their final drafts. Citing the goal of learning how to cook spicy chicken, a student wrote “Then I asked her [his aunt] to teach me in person during the summer vacation” after he failed to learn it through video chat with her while in the U.S. Additionally, students whose first drafts didn’t include statements about the retrospection of their goals (n=10) either added these statements or expanded their statements to include new details about the outcome of the event, resulting in 40% increase in goal retrospection statements. For example, a student who described the event of preparing a fancy meal for important guests at her house described the success of her family’s endeavors in one statement in the first draft: “The food smelled and looked magnificent,” while she wrote in more detail about how “[t]he guests commented on food, complimenting my parents” in the final draft.

Interestingly, students tended to describe the process of achieving their goals in extensive details in their final drafts. Almost all students elaborated on the steps they and other people in their narrated events took to achieve the (often implicitly) set goals and how these processes were effective in achieving the goals, which explains the 44% of change in goal process across drafts. One student, for instance, described all the smaller steps he and his friends took to have a traditional Christmas party while spending their vacation in Singapore. The student wrote about buying and preparing food, making cupcakes, exchanging gifts, and cleaning up after the party, describing the small details of their communication and how all that process made them enjoy and share a memorable Christmas party.

Intrigued by these findings, I wanted to understand why many students took the time to add all those details to their narratives. I read through students’ revision plans and found that many students noted how they had been inspired by the vivid details in the two literacy narratives we had discussed in class tand therefore decided to “add more details to the process of how to cook the fried fish” and “add more details about communication over food,” as two students stated. A number of students explained how they would add communication and dialogues to their revised drafts in order to capture the communication element required in the assignment (see Figure 2 above). Although I didn’t ask students to use dialogues in their narratives, the two DALN literacy narratives contained intermittent dialogues: a one-sentence dialogue like “We’re moving to America, son” (Varhan, 2013, p. 1) or a longer conversation between the teacher and student in “The Art of Cursive Writing” (Park, 2015). One student wrote about her decision “to add more conversation when we eat dinner and what we learned from each other,” citing “the notes from the two narrative essays” as her rationale. Thus, the discussion of the two literacy narratives seems to have boosted students’ confidence to take risks and add dialogues to their final drafts, supporting Corkery’s (2004) argument that narrative writing, and I add reading, support pedagogy centered on confidence-building. I further argue that the fact that those two narratives were written by multilingual writers contributed to students’ decision to adventure into new writing strategies. Students were able to identify with those writers (Corkery, 2005), hence their decision to emulate the strategy of dialogues in their own narratives. These findings strengthen my argument that using literacy narratives written by multilingual writers develops international multilingual writers’ reflective writing skills, and affirm the DALN’s value as an inventory from which teachers can draw narratives that suit different purposes and themes.

It is clear that reading and discussing the two literacy narratives as an intervention strategy and a literacy practice played an important role in shifting students’ attention from the outcome to the process of reaching that outcome. As significant as these findings about the first element of reflection are, the gains in the second element appear to be even more significant.

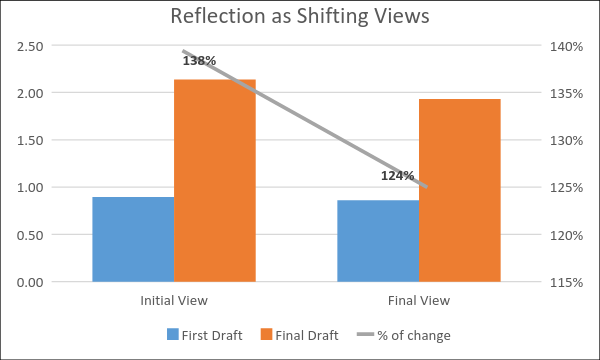

Reflection as Shifting Views

Statistical analysis of the two sub-categories of shifting views (initial and final views) as the second element of reflection examined in this study showed that the changes in students’ reflection were statistically significant with t=13.4 at p<=0.05. Not only did all students elaborate on how their feelings, thoughts, and positions had changed during the course of the narrated event, they paid equal attention to the views of other people in their stories as well. Beyond the brief though strong t value, the percentage of change in the mean number of statements of initial and final views was 138% and 124%, respectively, as you can see in Figure 7. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis of students’ drafts reveals substantial gains in students’ abilities to portray and compare the change in views.

In his first draft, one student expressed his skepticism of veggies and the vegetarian cuisine served at his first-ever private chef’s home dinner, writing “I was not interested in veggie dinner at first, because I thought vegetables are very boring,” before he tried the food and “had a new understanding of vegetables” because vegetarian dishes were prepared from “rich nutrient materials.” Even though the student wrote about the change in his perception and understanding of vegetarian food, he did not account for the change in his position beyond the simple reason of appreciating the materials used in cooking these dishes. The student’s description of his new perception of vegetarian food in the final draft demonstrated reflections on the non-tangible elements of the dinner, saying “it was not only just a delicious food, but also a sense of emotion, a traditional culture, and ingenuity.” The student seems to have shifted his attention from the simple observation that may have changed his opinion of the unique dinner experience to the more significant reasons that may have made him enjoy that dinner regardless of his initial skepticism and rejection of vegetarian food. Such a shift reveals an enhanced approach to reflection by moving from the visible and concrete to the invisible and abstract aspects of a situation.

Students were able not only to capture the change in their own feelings and thoughts in the narratives, but also to demonstrate their ability to detect other peoples’ changing views. In his first draft, one student described how “[t]he moods of everyone are pleasant” at the beginning of a high school graduation, but dinner changed—“[s]uddenly, everyone was quiet”—when the friends realized that that may be their last time to see each other. In his final draft, though, the same student extensively described the change in his friends’ feelings:

The ice cream, softened and began to melt, which made it less delicious. Maybe this is a symbol of our disappearing happiness for separation. Suddenly, everyone was quiet. Nobody spoke the first sentence. I saw a sad and sentimental expression on the face of each person.

In his revision plan, that student explained his decision to “describe more in the change of people’s moods because of communication and how the different mood is reflected in the food.” This plan provides an insight into the student’s thinking and reflection process and how he developed that exquisite interpretation of the relationship among food and communication and emotions. The student shifted his attention from the simple and visible emotions to the possible causes of the change in emotions, demonstrating a sophisticated reflection skill.

I argue that that increased attention to the inner selves by trying to capture and decode the unseen delicate feelings and thoughts in writing is a rewarding result of using the DALN narratives in this study. As one student wrote in her revision plan, crediting the influence of the DALN narratives for her understanding of reflection, “[a]fter reading the essay written by a Belarus student, I found that this inquiry is not just about dialogue, what worth more details is the reflection.” We can better understand the student’s reference to the “Another Land, Another Language” (Varhan, 2013) narrative by looking at the ways that writer from Belarus was keen on recording his initial and shifting views of the “practice exercises from an English workbook” his mother made the whole family do (p. 2). At the beginning, the writer “thought of the constant learning exercises to be tedious at most” but looking in retrospect at the experience, he became “very thankful that I had to do that,” not only because of learning a new language but more importantly because of the sense of togetherness he and his family developed through those practice exercises: “The experience brought us closer together and the uniqueness of the activity made it seem exciting and fun. We would laugh at each other when one of us got something wrong, or mispronounced a word” (Varhan, 2013, p. 2).

The data has shown little improvement in writing about goals and

huge gains in writing about shifting views; my analysis now moves to

changes in retrospection.

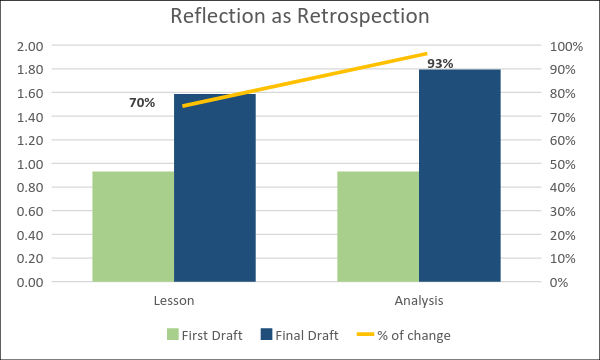

Reflection as Retrospection

Unlike the huge gains in shifting views as an element of reflective writing between first and final drafts, retrospection seems to have slightly changed across both drafts with t = 7.3 and p<=0.09. Even though there was a notable percentage of change in the mean number of statements about lessons (70%) and the analysis of lessons (93%), the change was not of strong statistical significance. Students didn’t seem to write much about the lessons they may have learned from the experiences they chose to narrate. The relatively bigger increase in analysis of lessons than lessons themselves, seen in Figure 8, indicates attention to details while attempting to aggregate all the minute specifics of a situation. In other words, students were more attentive to interpreting those lessons than merely listing or stating a lesson. These choices and decisions could be attributed to the newly enhanced attention to details that most students developed in their final drafts, as evident in the other elements of reflection discussed above.

A good example of this interest in interpretation comes from one student’s drafts. At the conclusion of the first draft of a narrative about a high school graduation dinner with friends and a teacher, the student wrote “[i]t is my belief that communication helps us strengthen our common beautiful memories,” a simple, almost clichéd, sentence that lacks details, personality, or reflection. This sentence was transformed in the final draft:

Communication is really a magic power which changes people’s mood. When we feel happy, everything we eat will become sweet and delicious. But when we [are] in a depressing emotion and feel upset, the food will not taste good anymore.

The clichéd lesson about communication and memories changes into a more elaborate and thoughtful analysis of how communication can induce various moods that may alter our taste of food. The student furthered the analysis of the lesson and wrote about the plans he made on the bus going back home to stay in touch with high school friends after they depart for college.

In her revision plan, another student wrote “In my reflection, I’d like to talk more about how food got me closer [to roommate] and made me communicate in a more meaningful way.” That student chose her first experience cooking and sharing food with her new roommate as the center of the narrative. In the final draft of the narrative, the student extensively wrote about what she had learned:

Sharing food is really a good step to make new friends and integrate into our new life and study in the USA… When I have some troubles and feel embarrassed to talk with friends in a formal way, I’d like to share food with them. It will be easy to communicate my daily life with each other.

Later in the narrative, the student wrote about how that lesson was put into action when she was stressed because of a bad grade and how sharing food made it easier to share the negative experience and seek advice from her roommate.

The exclusive focus on one moment of reflection in these two students’ narratives is likely to be the result of reading and discussing “The Art of Cursive Writing” (Park, 2015) literacy narrative, in which the writer describes his new appreciation of cursive handwriting and what he’d learned from that new perspective: “learning how to write in cursive has shown me that handwriting can show character, personal history and most of all how much effort goes into every handwritten word” (p. 4). The excerpts from the two students’ final narrative drafts demonstrate a similar approach of focusing on the moment of revelation of how communication over food shared with others can carry different meanings and prompt novel understandings.

Contrary to Yancey’s (1998) concept of “constructive reflection” that aims to help “students to articulate what they are learning,” I didn’t ask students to write about what they may have learned (p. 60). I didn’t want to force students to either fabricate a lesson to satisfy me or to impose a loaded interpretation of their experiences. This is why I wasn’t surprised by the lack of reflection on the lessons or their interpretation in students’ first drafts.

Things changed in the final drafts, though, as students embarked on interpretation and analysis of the lessons they accumulated from those narrated experiences. The apparent attention to the causes, consequences, or significance of the lesson rather than the lesson itself can be attributed to reading the two DALN literacy narratives I used. While Park (2015) and Varhan (2013) don’t write much about the lessons they learned, both describe in much detail the significance and future implications of the learning experiences, which could have inspired students to entertain more interpretations of lessons in their final drafts. Students’ interest in analysis and interpretation of past experiences and the possible lessons learned from them signifies a sophisticated and complex level of reflection on their “unexamined assumptions” (Leki, 1992, p. 66), reflection that Yancey described as “meaningful” because it was “situated… in context” (1998, p. 63).

May – June 2016 Challenge Concluded

At the outset of this research, I wanted to answer these research questions:

- Does using two literacy narratives from the DALN archive influence the reflective writing of international multilingual students?

- To what degree do the reflection elements of the goal, shifting views, and reviews change in a subsequent draft of a reflective writing assignment?

- How do the statements of the goal, shifting views, and lesson change in a subsequent draft of a reflective writing assignment?

The statistical and qualitative analysis of 29 international multilingual students’ first and final drafts of food-and-communication narratives indicates that the use of the two literacy narratives from the DALN archive has influenced the reflective writing of these students. The analysis has demonstrated different degrees of change in the three elements of reflection under study: strong statistical significance in shifting views, negligible statistical significance in retrospection, and no significance in goals. Despite the varying degrees of quantitative change in the three elements of reflection, qualitative change was evident and meaningful in all three elements. Not only does the analysis answer all research questions addressed in this study, it illuminates various benefits of the DALN materials in the writing classroom, and for teaching writing to international multilingual students in particular. Before I move on to discuss those benefits and their pedagogical implications for teaching writing, it is crucial to acknowledge that the small sample size in this study (n=29) does not warrant any generalizations. Nevertheless, the discussion below opens the door for more integration of DALN materials in the writing classroom and for further research on the use of the archives materials in teaching writing.

Methodologically, pairing up quantitative and qualitative analysis in this mixed-method study has enabled a rich, deep understanding of reflection that, I argue, wouldn’t have been possible had I chosen one methodology only. The quantitative analysis yielded mixed results about the change that seems to have happened in all three elements of reflection in students’ final drafts. The statistical analysis thus has masked the actual changes and gains that occurred in two elements of reflection, which was substantiated by the qualitative analysis. Conversely, qualitative analysis of data would have obscured the degree of change that happened in the elements of reflection individually or collectively. Even though the quality of change matters more to writing teachers, the degree of change is important in order to assess the usefulness of the intervention process and possible areas for improvement in instruction and use of DALN materials in the classroom.

Reflection as Literacy: The Details, Perspectives, and Context

As discussed in the previous sections, the qualitative analysis captured a significant improvement in multilingual students’ reflective writing skills from the first to the final drafts. Students appeared to have developed better understanding of the importance of details as they were describing the success or failure of achieving their goals. The amount of descriptive details and dialogues they added to account for the outcome in their narrated events indicates enhanced reflective thinking that pays more attention to the process of achieving the goal instead of a simple statement about the achievement of that goal. Yancey (1998) describes “the processes by which we know what we have accomplished and by which we articulate accomplishment” as “reflection” (p. 6). This elevated attention to details also signals enhanced literacy because Barton (2007) asserts that literacy is “tied up with particular details” that shape the literacy event and make it unique to certain people in a very specific situation (p. 3). As they reflected on their narrated events, students seemed to have zoomed in on the minute details they had previously overlooked, thus indirectly transforming everyday food-and-communication situations into literacy events, or sites of reflection through the written word. Such novel conceptualization of reflecting on everyday life events challenges as well as broadens definitions of literacy (Bloome, 2013).

Similar to the brief descriptions of goals and the process of achieving them in the first drafts. students’ narratives contained very short accounts of their views and emotions as they went through the narrated experiences. That observation was not surprising to me, and Aneta Pavlenko’s (2002) argument that narratives are “not purely individual productions” is significant to interpret students’ refraining from exposing their inner thoughts and feelings in their first drafts (p. 213). Of importance here is Pavlenko’s discussion of narratives being “shaped by social, cultural, and historical conventions” that make the narrative writer consciously or unconsciously make certain decisions about details to include and those to leave out. For example, Leki (1992) explains how asking international students from certain cultures to write about personal experience may entail “more personal disclosure than they can tolerate” (p. 67). This is why international multilingual students from certain cultures (e.g., Chinese students in this study) may experience discomfort or lack of confidence unveiling their feelings and thoughts in writing. I wanted students to reflect more openly on their views on the events they portrayed in their narratives without having to push them hard out of their comfort zone. Reading through the literacy narratives seems to not only have directed students’ attention to the importance of discussing their thoughts and emotions, but also pushed them out of that comfort zone as they realized that the Korean writer of “The Art of Cursive Writing” (Park, 2015), another multilingual writer, expressed his feelings and thoughts without barriers. Chinese and Korean students are expected to be discreet and quite conservative in expressing their feelings and thoughts. Recognizing this shared culture with the Korean writer may have been the reason Chinese students in this study felt more at ease elaborating on their feelings in their final drafts. Students felt inclined to explain how communicating with others changed their thoughts and feelings during the course of the experience, thus revealing more refined introspection and reflection on the newly developed perspectives of their experiences.

Students’ intricate sketching of their and others’ newly formed perspectives while revising their narratives supports Selfe and the DALN consortium’s (2013) argument that “[s]torytellers use personal accounts to position themselves within the contexts of their own lives” while composing narratives laden with self-interpretation and self-reflection on the narrated event. These students saw the outcome of these events through a fresh lens that enabled them to discern the evolution of their own and others’ feelings and positions throughout the narrated event. Bamberg (as cited in Selfe & the DALN Consortium, 2013) considers this cognitive discerning the “product of discursive story-telling,” in this case reading a story (one of the DALN narratives) and writing a story (the food-and-communication narrative). In other words, the engagement in the literacy event of reading and writing narratives created a unique literacy practice that seems to have advanced and nurtured multilingual writers’ reflective writing skills.

Moreover, students used their narratives as sites of redefining themselves and the events they narrate, “formulat[ing] their own sense of self” (Selfe & the DALN Consortium, 2013) or reflecting on how the context of the event (the food they had and the communication they exchanged with others over food) may have shaped them, the consequences of the event, and their interpretation of both. Selfe et al. (2013) maintain that “this self changes slightly” since the narrative occurs at a different social, material, and in this case, geographical context. Furthermore, the reflection on the self in that event changes as well because of the changed context. This prime interest in the role of the context in narrative writing and the reflection on the narrated events is what Selfe and the DALN consortium (2013) call the narrative turn that acknowledges the social and cultural discourse of the narrative. Similarly, literacy, in New Literacy Studies (NLS), is defined as a social act that takes place within certain contexts that shape both the nature and the effect of literacy (Street, 2003). Bloome (2013) explains Street’s ideological model of literacy and asserts that literacy isn’t a stand-alone concept. As students repositioned themselves in the distant contexts where the narrated events originated, they seemed to perceive and redefine those contexts differently; they seemed to see beyond the visible events, reaching deeper interpretations of the events and the lessons learned from them. Reflection became a product of the literacy events of reading, analyzing, and discussing the two literacy narratives from the DALN archive and of writing and revising the food-and-communication narratives now recontextualized.

Challenge Continued: DALN in the Classroom

The use of DALN materials has clearly improved international multilingual students’ “reflection on what worked out and what need improving” (Donovan, Bransford, & Pellegrino, 2000, p. 12). Donovan, Bransford, and Pellegrino asserted that metacognition, or “the ability to reflect on one’s own performance” (p. 97), develops gradually as the individual goes through certain experiences. Students in this study appear to have gradually developed their reflection skills through the discussion of the two literacy narratives acquired from the DALN archive, devising their revision plans, and incorporating details in their revised final drafts.

Whether the reflection parts added to the narratives were a product of reclaiming the past and shaping it in the light of the new literacy students were acquiring (Bloome, 2013), or whether it was a product of noticing the minute details in the event they narrated, reflection was a product of the literacy event of reading, analyzing, and discussing the two literacy narratives from the DALN archive as an intervention strategy that aimed to improving the reflective writing skills of multilingual student writers.

Similar to the survey results in Kathryn Comer and Michael Harker’s (2015) research on the DALN pedagogical uses, the results of this study should encourage more writing teachers to dig deep in the 7000 narratives in the DALN archive (McCorkle, 2016) to find materials that they can use to teach and research a wide variety of topics. The recent bibliography of publications, conference presentations, and course themes inspired by the DALN archive (as documented on The DALN Blog) demonstrate that the archive materials lend themselves to topics such as visual and digital literacy, voice, cross-cultural rhetoric, and multilingualism, to name only a few possibilities.

When identifying the possible areas of interest for teachers in the DALN archive, Selfe and the DALN Consortium (2013) included “literacy narratives and what they can tell us about teaching and learning,” pushing writing teachers to explore creative uses of the archive materials. They rightly acknowledge that the richness and unruliness of the DALN narratives cannot be restricted in the five areas of interest they identified. There is always room for pedagogical innovations that nuance, complicate, refine, and enrich our teaching of literacy and reflection. Following Chandler and Scenters-Zapico’s (2012) assertion that literacy narratives have been often used for research and “re-imagining writing pedagogies” (p. 185), I offer a number of pedagogical suggestions inspired by this study in this final audio reflection.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Ms. Titcha Ho for her substantial help with coding data and discussing the coding system in the process of validating the system and the findings of the study. Ms. Ho is a lecturer in Writing and Critical Inquiry at the State University of New York at Albany where she teaches second language learners. She is also a Ph.D. Candidate in Composition and TESOL at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

References

Amicucci, A. N. (2011). Using reflection to promote students’ writing process awareness. CEA Forum, Winter/Spring, 34-56.

Barton, D. (2007). Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Bloome, D. (2013). Five ways to read a curated archive of digital literacy narratives. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Brandt, D. (2001). Literacy in American lives. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bruner, J. (2004). Life as narrative. Social Research, 71(3), 691-710.

Bryson, K. (2012). The literacy myth in the digital archive of literacy narratives. Computers and Composition, 29(3), 254–268.

Chandler, S. W. (2013). New literacy narratives from an urban university: Analyzing stories about reading, writing, and changing technologies. New York, NY: Hampton Press.

Chandler, S. & Scenters-Zapico, J. (2012). New literacy

narratives: Stories about reading and writing in a digital age. Computers

and Composition, 29(3), 185-190.

Comer, K. B. & Harker, M. (2015). The pedagogy of the digital

archive of literacy narratives: A survey. Computers and

Composition, 35, 65-85.

Corkery, C. (2005). Literacy narratives and confidence building in the writing classroom. Journal of Basic Writing, 4(1), 48-67.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

DeRosa, S. (2002). Literacy narratives as genres of possibility:

Students’ voices, reflective writing, and rhetorical awareness.

Retrieved from http://www.ibrarian.net/navon/paper/

Dewey, J. (2012). How we think. Lexington, KY: Renaissance Classics.

Donovan, M. S., Bransford, J. D, & Pellegrino, J. W. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school: Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Eldred, J. C. & Mortensen, P. (1992). Reading literacy narratives. College English, 54(5), 512-539.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Education research: An introduction (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Greene, K. (2011). Research for the classroom: The power of reflective writing. The English Journal, 100(4), 90-93.

Giles, S. L. (2010). Reflective writing and the revision process: What were you thinking? In C. Lowe & P. Zemliansky (Eds.), Writing spaces: Readings in writing (Vol. 1, pp. 191-204). West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice: New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lauer, J. M. & Asher, J. W. (1988). Composition research: Empirical designs. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lawrence, H. (2013). Personal, reflective writing: A pedagogical strategy for teaching business students to write. Business Communication Quarterly, 76(2), 192–206.

Leki, I. (1992). Understanding ESL writers: A guide for teachers. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

McCorkle, B. (2016). The state of the DALN. Paper presented at the Computers and Writing Conference, St. John Fisher College, Rochester, NY.

McCorkle, B., Harker, M., & Comer, K. (2015). Call for papers: The archive as classroom: Pedagogical approaches to the DALN. Retrieved from https://thedaln.wordpress.com/2015/06/10/check-out-the-new-cfp-for-the-archive-as-classroom-pedagogical-approaches-to-the-daln/

Park, J. S. (2015). The art of cursive writing. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/fd6df6c9-69fb-4010-927d-ceaf5e306779

Pavlenko, A. (2002). Narrative study: Whose story is it, anyway? TESOL Quarterly, 36(2), 213-218.

Scott, J. B. (1997). The literacy narrative as production pedagogy in the composition classroom. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, 24(2), 108-117.

Selfe, C. L., & The DALN Consortium. (2013). Narrative theory and stories that speak to us. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.),Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Srnka, K. J. & Koeszegi, S. T. (2007). From words to numbers: How to transform qualitative data into meaningful quantitative results. Schmalenbach Business Review, 59(1), 29-57.

The DALN Blog. (2016). Bibliography. Retrieved from https://thedaln.wordpress.com/ bibliography/

Ulman, H. L. (2013). A brief introduction to the digital archive of literacy narratives (DALN). In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/tah State University Press.

Varhan, D. (2013). Another land, another language. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/eace5852-df20-4fc1-80fc-3230f90a13db

Yancey, K. B. (1998). Reflection in the writing classroom. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.