Year of Living DALNgerously: Breakthrough Encounters with Archival Pedagogy

BILL FITZGERALD & BRYNN KAIRIS

ABSTRACT

This dialogic essay recounts a “year in the life” of an instructor (Bill) and undergraduate student (Brynn) in their mutual encounters with the DALN as a site for teaching, learning, and scholarship. Initial exposure to the DALN in an undergraduate course on “Community and Literacy” marks a turning point for both as a result of the affordances of the DALN that allow for significant growth and shift of perspective. For Bill, teaching with the DALN enabled him to own his desire to develop as a researcher; for Brynn, learning to use the DALN as a resource encouraged her to likewise embrace a new identity of a scholar in addition to that of a student. This year continued into a second semester in which Bill taught a graduate course in research methods in composition and literacy and Brynn found herself developing a publishable project through archival research in the DALN. In a postscript, Bill and Brynn reflect on the ways that this year of living DALNgerously continues to impact their growth as scholars (both), teachers (both), and writing program administrator (Bill) and address the potential for the DALN to serve as a site for transformation not only of individuals but of the field of English studies itself.

***

Much has been written about the affordances of archives for undergraduate researchers. In 2002, Susan Wells described “three precious gifts” that archives bestow upon students and teachers, citing their “resistance to our first thought, freedom from resentment, and the possibility of configuring our relationship to history” as crucial aspects of research that other spaces and methodologies do not provide (p. 58). Since then, scholars such as Wendy Hayden (2015), Kathryn Comer and Michael Harker (2015), and others have taken up the call, turning their attention to the rich potential that archival work presents to challenge students’ (often) narrow definitions of “research.” Archives are spaces where knowledge isn’t simply absorbed and synthesized from secondary sources—it’s where knowledge is made. Archival work allows students to engage in authentic research practices, contributing to real conversations in the academy.

As an archive, the DALN is unique. This multifaceted space allows both students and teachers to interact with the archive in a variety of ways. It goes beyond the already vast number of affordances that archives provide for the classroom, allowing visitors to inhabit new identities as they take on various roles as contributors, curators, researchers, etc. (Comer & Harker, 2015). Interacting with the archive allows students to claim agency as members of the academy making legitimate contributions to knowledge (Grobman, 2009). For teachers, the archive provides tools to help students to understand and engage in research.

This essay recounts a year in the life of one such teacher (Bill) and student (Brynn), each of whom was energized and transformed through their respective encounters with the DALN and for whom the DALN continues to be an inspiration and a resource for teaching and scholarship. In a number of respects, as recounted here, this initial encounter was accidental, more a product of opportunity than design. Working with the DALN proved to be a convenient solution to a short-term problem. But as we argue in this chapter, particularly by example, the affordances of the DALN are many—and chief among them, perhaps, is that of serendipity. You don’t know what you’ll find when you delve into the DALN.

Here, in two parts, Fall 2013: Encounters with the DALN and Spring 2014: Researching with the DALN, we take a dialogic approach to this essay, with each of us leading off and in turn responding to the other with a complementary story about the DALN as a site for teaching or learning and as a site for research. In a postscript, we trace the ongoing impact of that academic year. Of course, our admittedly whimsical title for this essay references a classic of modern cinema, Peter Weir’s The Year of Living Dangerously, the 1982 film depicting an Australian journalist (played by a young Mel Gibson) navigating the tumultuous political scene of 1960s Jakarta. While our escapades in the DALN might not have approached the level of intrigue and danger as the film’s representation of the overthrow of the Sukarno regime by Suharto, it was nonetheless a year of transformation and, in its own way, dalngerous.

I. Fall 2013: Encounters with the DALN

Bill

I did not expect that my initial encounter with the DALN would have such a transformative effect in my career, coming as it did at an inflection point in the shift from pre- to post-tenure and, with that shift, changed expectations for teaching and research. Having run an academic gauntlet with a dispensation to light into new territory, what would I now profess? It turns out that 2013-14 was a “year of living DALNgerously” and a watershed in my development as a scholar and educator.

Before I Learned to Live DALNgerously

Comfortable as the “resident rhetorician” in my department, I considered myself “old school.” I papered over shortcomings with technology and lack of familiarity with research methods by teaching textual analysis supported by critical theory. Hesitant to leave my comfort zone, I envied colleagues engaged in data-driven inquiry, including archival and qualitative research. My colleagues in literature didn’t seem to notice or care that I was researchphobic, but I did.

If anything moved the dial, it was a course, “Introduction to Writing Studies,” I taught in Fall 2009. In itself, it wasn’t a great departure from a reading-based, library-research model that gave predictable shape to my teaching, but it included an opportunity to mentor a student in off-campus research at a store-front literacy center, Mighty Writers, in South Philadelphia. This student, Marc Hummel, would publish his work as “Community Writing Centers and Genre Literacy” in Volume 9 (2011) of Young Scholars in Writing: Undergraduate Research in Writing and Rhetoric. Even as Marc’s project involved textual analysis of early learners’ writing practices (familiar territory for me), this encounter with literacy studies, and community literacy in particular, troubled settled categories in my teaching and research. My scholarship was centered in the rhetoric of religion, especially prayer (FitzGerald, 2012). My teaching reflected broad training in writing across the curriculum and professional writing. At Rutgers-Camden, I taught undergraduate courses in style and media and graduate courses in rhetorical theory, discourse analysis. At this point, however, I began to imagine a role for literacy studies at an urban research university like ours, especially at a time when civic engagement had become a watchword for us, institutionally. It didn’t seem that we would hire a literacy scholar anytime soon, so if students were to be introduced to literacy studies, that responsibility was mine.

Deciding to branch out in the direction of literacy studies was motivated by recognition that we were lacking a significant subfield of English studies. Over time, I arrived at a position that the fields of rhetoric and composition (and even writing studies) were not capacious enough to address the mission of English in the new century and that literacy studies, in its scope and its methods, was increasingly central to that mission. This insight was further sharpened by a realization that literacy studies represented an affirmation of an engaged, activist pedagogy rooted in norms of social justice. It would be a stretch to claim I thought all of this through, only that I had begun to grapple with how to understand my work as a member of a discipline and my role as a citizen of my campus and community. I soon come to realize that literacy was a productive frame to understand ever-evolving commitments to pedagogy that invited students, including undergraduates, to become scholars through research and reflective practice.

Thus began efforts to add literacy to the fields of rhetoric and writing studies that defined my teaching with a graduate-level survey in Spring 2011. This course, “Literacies in 21st-Century Contexts,” required getting up to speed on a vast body of literature and accepting my amateur status learning with my students. I turned to Ellen Cushman’s Literacy: A Critical Sourcebook (2001) to anchor essential readings that included David Barton’s Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language (1994), Deborah Brandt’s Literacy in American Lives (2001), and Shirley Brice Heath and Brian Street’s On Ethnography: Approaches to Language and Literacy Research (2004). We turned to good friend and local colleague Eli Goldblatt for his Because We Live Here (2007). It was exhilarating to deepen formerly piecemeal encounters with literacy scholarship and gain insight into various strands and schools of literary studies beyond historical and media frameworks, e.g., debates on “orality vs. literacy” involving Ong (1982), Havelock (1963), Goody (1987), Olson (1996). I finished the course with a map of the field in its contested complexity, aware of the leverage literacy studies offered to more familiar domains of composition theory and practice.

This overview included attention to the New London Group with its focus on multiliteracies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000) and related work by Cynthia Selfe and Gail Hawisher (2004) on the texture of literacy in relation to technology. Beyond these theoretically informed case studies, the course offered a framework for research on literacy using ethnographic methods. In truth, here the course came up short with little time for students to develop a research project. Even so, students benefitted from exposure to methodological concerns in the small projects they conducted. For example, one student, a teaching assistant, read her own students’ email practices using Heath’s “literacy events” (1983) and Mary Louise Pratt’s “contact zones” (1999) to better understand divergent expectations for email etiquette.

Flirting with DALNger

I cite details of this 2010 course because it laid a foundation for the undergraduate course I would teach in Fall 2013 in which the DALN would play a determinative role. Reviewing my graduate syllabus, I see that I introduced the DALN as early as the second week, but only in passing. I had yet to realize its significance as a site of transformative pedagogy. I would do so only after a year of using the DALN in several courses with new approaches to teaching.

I returned to the subject of literacy after two years upon selection as a Civic Engaged Faculty Fellow in 2012. Each of us in this first cohort of a new campus initiative were to develop or retool a course to take students beyond campus walls and engage with community partners. My proposed course in “Community and Literacy” was clear enough: students would learn about literacy and apply that knowledge in some sort of fieldwork, perhaps at a neighborhood tutoring center (like Marc) or the public library (recently relocated onto our campus). The course would evolve from its initial hazy vision, in part inspired by exposure to the DALN. I offered “Community and Literacy” in Fall 2013.

By this point, lack of substantive exposure to literacy as a vibrant field in our curriculum was all the more glaring. I started to see multiple strands of my interests as a teacher coalesce. Prior insights about literacy as a productive framework for directing the activities of graduates and undergraduates began to align with campus priorities in civic engagement, experiential learning, and undergraduate research. My new role as a leader in faculty development and assessment brought me into contact with a wider network of colleagues and administrators, causing me to feel less an outlier in English and more a participant in a broader curriculum. While such feelings were nascent, the interdisciplinarity of literacy prepared me to think and act differently from my previous role as leader in a salon of ideas. I came to see myself primarily as a mentor of research, but now with a better sense of the kinds of research I could mentor.

While I wasn’t sure I could bring this course into regular rotation, it was important, at least, to represent the field to undergraduates. The course that I arrived at in Fall 2013 surprised me, for I still regarded myself as an amateur anxious of my ability to represent the field adequately. It’s one thing to teach a graduate survey; it’s another to ask undergraduates to engage with their experiences, with typically unarticulated assumptions about education, and with an array of forces that shape them as students, citizens, consumers, and producers. I wanted them to understand how their own literacies had “sponsors” (Brandt, 1998). And part of the “another” thing, I understood, was a responsibility to prepare students to be contributors to knowledge. My undergraduate course asked students to step into the role of researchers with respect to community and literacy. Enter the DALN.

Living (and Teaching) DALNgerously

In some ways I stumbled onto the DALN as a fall-back position to address an embarrassing problem of not having found community partners for a course on “Community and Literacy.” For multiple reasons, efforts to locate appropriate off-campus venues for over 25 students proved unproductive. Beyond logistical issues of placement, scheduling, and transport, I was frankly unprepared for the planning involved, not least in addressing IRB protocols if my students were to engage in human-subject research. Through the spring and summer of 2013, I began to see how the DALN could anchor the course. As can be seen in the course description that greeted students on the first day (Appendix A), even as the semester began I was intent on connecting my class to sites of literacy sponsorship beyond the campus. That plan did not unfold, but what did was a satisfying journey for me and, I believe, most of my students, a mix of English majors and others taking the course as an elective.

From the start, as this description shows, the DALN served as a catalyst to move us beyond the comfort the “banking model” of education we soon read about (Freire, 1970). The key insight was the potential of the DALN to make visible the activities of literacy beyond the voices of academia and to invite students to contribute their voices. Again, from the start, the DALN functioned as counterpoint to what could have been, apart from it, an undergraduate variation on the graduate level course of three years earlier. But literacy narratives! In a digital archive! This was precisely what was missing before—the opportunity to encounter and contribute to a living data set. Looking back, it seemed strange that the graduate course had nothing on the genre of literacy narratives. It was easy, now, to see a passive avoidance of unregulated learning in favor of vetted texts. If anything changed from 2010 to 2013, it was openness to experimentation and willingness to see where the DALN might take us.

At the same time, the new course bore a strong resemblance to the former, being in part a survey of accessible scholarship. Each week was a class devoted to texts that demonstrated the relevance of literacy studies. Readings included Kathleen Blake Yancey on “Writing in the 21st Century” (2009), Beverly Moss on “Creating a Community: Literacy Events in African-American Churches” (1994), Deborah Brandt on “Sponsors of Literacy” (1998), Harvey Graff on “Literacy Learning in the Nineteenth Century” (1987), Paolo Freire on “The Banking Concept of Education” (1970), Eli Goldblatt on “Alinsky’s Reveille: A Community-Organizing Model for Neighborhood-Based Literacy Projects” (2005), Anne Ruggles Gere on “Kitchen Tables and Rented Rooms: The Extracurriculum of Composition“ (1994), and excerpts from, among others, Walter Ong (1982) and Jack Goody (1987) on differences between orality and literacy, Jared Diamond on the origins of writing (1999), and Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole on literacy among the Vai people (1981). Beyond these works, we considered expanded notions of literacy in new media contexts, including James Gee on “What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy” (2003) and a range of reading on multiliteracies in daily life and in contexts of schooling. That was a lot of ground to cover! Class discussions were lively, as students unearthed foundations of their formation as students (citizens, workers, etc.) and of institutions that shape those identities.

The most distinctive contribution to the course, assigned in its entirety, was Mike Rose’s Lives on the Boundary (1989). For all the attention paid to this signature text and its resonance with my own journey from the working class to the halls of academe, I had never read Rose until this course. Our encounter with Rose’s autobiographical literacy narrative spanned eight classes across October and lent considerable depth to the emerging portrait of literacy as both lived experience and the product of complex and contending social forces, especially in the nature of schooling. Repeatedly, students wondered why they had never been exposed to this kind of material.

I can’t say what effect reading Rose might have had on my students’ literacy narratives, for those came early, in September. Alongside readings mapping the terrain of literacy studies, we delved into the resources of the DALN from the outset. Notwithstanding a thematic of community and literacy, putting the DALN front and center set up an activity-rich interplay of reading, writing, and research, a dynamic I sought to keep in productive tension. The planned for and the serendipitous, the academic and the everyday, the self and other—these were binaries I consciously built into the course. The plan, in short, was to prepare students to venture into their communities as researchers—agents of the DALN, if you will—to solicit, collect, and curate literacy narratives. Through such efforts, students were situated as archivists engaged in the complexities of real world data collection, curation, and analysis, a process at once messy and organized. The desire to place students into roles as researchers, in contrast to the familiar role of student, was front and center in my thinking. While this plan did not unfold exactly as anticipated, it more than delivered on its goal to give students authentic research experiences.

Students were introduced to the DALN in the first week with an assignment to poke around, finding, describing, and summarizing narratives of interest and imagining further questions for the contributor (see Appendix B for the prompt). This opening offered a low-stakes entry to what for many is a strange environment: a seemingly random collection of materials on a topic few had much considered. Yet searching the DALN provided a glimpse of the range of experiences and perspectives archived therein. In the next class, students continued with a look at the DALN’s Resources and Table of Contents pages, its sample narratives, and its “What is a Literacy Narrative?” text:

A literacy narrative is simply a collection of items that describe how you learned to read, write, and compose. This collection might include a story about learning to read cereal boxes and a story about learning to write plays. Some people will want to record their memories about the bedtime stories their parents read to them, the comics they looked at in the newspaper, or their first library card. Others will want to tell a story about writing a memorable letter, leaning how to write on a computer or taking a photograph; reading the Bible, publishing a ‘zine’, or sending an e-mail message. Your literacy narrative can have many smaller parts—but they will all be identified with your name. For instance, you might want to provide a story about learning to read as a child, a digitized image of one of your old report cards, a story about writing a letter as a teenager, a photograph of you as a young child; a song you learned when you were in school…

As they did so, on their own and together in class, they also began to compose their own micro-narratives in a regular feature of the course called My Literacy Log (See Appendix C for assignment outline). This kind of serial archival project in the tradition of a commonplace book has long been a staple of my pedagogy, adapted to a given course: style journal, collection of images, notebook of observations. Here, students recorded moments of literate activity and, in a process of curation, reflected on those activities in light of developing insight. At various times, they would share entries with others. On occasion, I asked students to apply a concept, like Deborah Brandt’s notion of literacy sponsorship (1998), to one or more of their entries.

Activities like these lead to direct engagement with the DALN as itself a sponsor of literacy. In the third week of September, students paired off for a Literacy Interview, during which they took turns conducting an extended interview of a classmate based on prompts and sample questions provided from the DALN website (See Appendix D for the prompt). Students thus practiced posing and responding to the DALN’s “basic literacy questions,” on parents’ and grandparents’ literacy histories; early and school age exposure to literacy; and literacy in relation to technology, among other themes. Looking back, I’m surprised we didn’t devote more time to this exercise to spark deeper acts of recall and reflection. Still, students were learning to engage others as solicitor and amanuensis and learning to represent their own experiences as well. Through this exercise, each student was able to generate “raw” material as a basis for their next DALN-inspired activity: composing their own literacy narratives.

The primary individual writing assignment (in contrast to the collaborative research project) of the course asked students to generate an extended (4-5 pages) “macro” narrative out of various “micro” narratives, or data points, they had inventoried. I offered little direction for this assignment beyond expectations to expand on their reflections. I did not require that their narrative follow a developmental or historical arc or that they address matters of schooling. I let narratives evolve “naturally” but staged that evolution through in-class drafting sessions and several deliverables: a first draft of at least 3 pages, a second draft at least one page longer, and a revised narrative after both peer and instructor feedback. The assignment spanned three weeks in all.

This assignment structure resembled a “composition course” model resulting in a formal paper. In ways I did not fully realize, I was asking students to compose a text at odds with much of the informal contributions to the DALN. By this point, students understood that their literacy narratives were imagined as potential contributions to the DALN. Yet here was a challenge that I only faced once the course had begun. Would I require students to contribute to the DALN? I concluded that doing so must be strictly voluntary, something they could do after the course. Even now I am uncertain how to bridge the gap between the school-sponsored essayistic literacy of my assignment and the wider range of performances found on the DALN. Or how to clear the ethical hurdle so that students can contribute to the DALN in real time.

Within the course, one additional assignment, Literacy Narrative 2, attempted to “solve” the academic literacy problem, asking students to hone in on “one significant moment, experience, or abiding interest” related to their literacy development in a brief (1-2 page) anecdote (See Appendix E for prompt). This end-of-semester effort invited students to move beyond a “paper” written for school, encouraging them to consider composing the piece as an audio essay. This, too, was imagined as a contribution to the DALN—encouraged, but not required. By this point, in early December, students were completing their major collaborative project, which directed their attention onto the world rather than toward themselves.

Using models provided by the DALN, in particular the edited collection Stories That Speak to Us, students undertook a six week “Fieldwork” project (See Appendix F for assignment outline). What in the months preceding the course was conceived as a project to collect and contribute literacy narratives to the DALN took a more conventional form as students channeled their research into a paper (and in-class presentation) analyzing multiple (3 to 8) literacy narratives that they had solicited. Again, although students were encouraged to invite interviewees to contribute literacy narratives to the DALN, none finally did. And I was careful (too careful?) to suggest that a successful project should yield some number of contributions.

Even so, students benefitted in their fieldwork, data collection, and analysis from the models, interview templates provided by the DALN and from the analyses of literacy narratives to be found in Stories That Speak to Us: Exhibits from the Digital Archives of Literacy Narratives (2013). In using Stories as a guide, we did not strictly follow any one curated exhibit so much as sample a range to acquire the concept of curation. Students were expected to discuss their interviews with a similar appreciation of emergent themes as contributors to Stories. Overall, my students, in teams of two or three, conducted their research more than satisfactorily. They were able to report on their fieldwork and findings through a conventional framework for research reports: introduction, methods, results, and conclusion. Aided by the resources of the DALN, they did so with insight and sensitivity.

Assessment

At the same time, one can critique this pedagogical leveraging of the DALN as a missed opportunity in several respects. At once an undergraduate survey in literacy studies and an experiment in archival research, the course tried to keep many balls in the air. The impact of exploratory encounters with the DALN was perhaps hit or miss. The invitation to do research locally in the context of an ongoing collaborative project like the DALN was different enough from what students were used to to be fully embraced by all. With greater planning, I might have used the archived literacy narratives to greater purpose or devised a more workable plan to solicit submissions. Going forward, I’d leave less to chance, while still allowing for the “serendipity” inherent in archival research (Kirsch, 2008).

As it turns out, however, I learned anew that I need my students as co-discoverers at least as much as they need me. Advanced planning is no substitute for patient, responsive unpacking of what is discoverable in encounters with the DALN, or any archive. And while planning is no guarantor of success, one benefit for me from this experience, applicable to future efforts, is witnessing how well students (like Brynn, below) do engage such materials.

Finally, I can say that we might have dug deeper to connect the lived experience of literacy as represented in the DALN—and in the lives of my students—with the scholarship we read. Our conversations were unexpectedly rich, but our DALN days and our reading days proceeded too much along separate channels. Of course, the course was a first effort to introduce literacy studies as a field to undergraduates. A one-off course for most everyone, in a curriculum with few occasions to re-engage students in related coursework, “Community and Literacy” was a testing of the waters. The course genuinely spoke to the needs of students receptive to the hidden curriculum that shapes their education, including their vocational sensibilities. Few courses in the repertoire allow students to explore that curriculum.

In retrospect, I might have found additional ways to help students leverage their encounters with the scholarship of literacy studies to their encounters with archived artifacts of literacy narratives, and vice-versa. I concluded that I had much to learn about the affordances of archives and about the challenge of fieldwork as inspired by the models of the DALN. That is, the experience opened my eyes to the untapped potential of archival research as a site for productive, accessible scholarship for undergraduates and graduates alike (Buehl, Chute, & Fields, 2012; Harker & Comer, 2015; Hayden, 2015; Ramsey, Sharer, L’Eplattenier, & Mastrangelo, 2009). It likewise confirmed that these encounters with the DALN must be understood not only in the context of literacy studies as a vital field too much neglected in the academy at large but also in the context of the kind of learning experiences we wish for our students. Working with them as they participated in processes of curation and analysis sharpened my focus for a return to the graduate classroom in the Spring semester of the year of living DALNgerously.

Brynn

Looking for More, but What?

As one of my first classes at Rutgers-Camden, “Community and Literacy” had a profound impact on my experience with the university. I transferred to Rutgers as a junior from Burlington County College (now Rowan College at BCC). I was a non-traditional student, pausing my education after high school to work full time as a marketing representative for a real estate firm. However, it’s always been my dream to teach. After a few frustrating years sitting at a desk I realized that the marketing world wasn’t for me. I enrolled in community college part time, eventually achieving associates degrees in Psychology and Education (concentrating in English). I arrived at Rutgers in the Fall of 2013 as a full time student majoring in English, eager to obtain my secondary school teaching certification.

I initially registered for Bill’s course because I thought it would help my teaching career. The course description promised community engagement, including partnerships with local schools and libraries. Up to this point, my education had not extended beyond texts and theory. I was hungry for real-world experience, impatient to enter the field and interact with students. Admittedly, part of my motivation for taking the course stemmed from anticipation of future job searches. I hoped that I might use this opportunity to network and build my resume. Yet I was also driven by a lurking restlessness. As a student, I wanted more from my education.

I knew nothing about literacy studies. My previous experience with English focused heavily on exposure to literature, including no rhetoric or composition theory whatsoever. Reading and writing had always played a prominent role in my life, but I wanted to engage with these activities in new ways. I was tired of feeling like an outsider, someone who read and summarized other’s work. Rather, I wanted to respond to and expand upon that work. I wanted to contribute in some way. At the time, I did not know that this need would be filled by my introduction to literacy studies and the DALN.

While the substance of the course was unfamiliar, the early weeks of “Community and Literacy” adhered to much the same classroom format I had come to expect. Per the usual, we read texts and discussed them in class, though Bill encouraged students to drive discussion in a way that I had not yet encountered. The texts themselves were fascinating. As we delved into major contributing works to the discipline of literacy studies, we explored things about the learning process that I had never been challenged to consider. I was especially drawn to Deborah Brandt’s idea of “sponsorship” (1998), not just as a future teacher and sponsor, but as an avid reader/writer who had encountered many traditional and non-traditional sponsors in her journey with literacy. I was affected deeply by David Bartholomae’s seminal text, “Inventing the University” (1986) and the work of Paulo Freire. Paired with Mike Rose’s Lives on the Boundary (1989), these texts forced me to consider my own identity as a student, including the ways in which I had been positioned in classrooms throughout my life. Questions began to percolate; they would eventually develop into the queries that would drive my first foray into research.

Wading into the DALN

In addition to guiding the class through a survey in literacy studies, “Community and Literacy” introduced students to the DALN. In the second week of the semester, nestled among readings from Yancey, Graff, and Gee, Bill tasked us to explore the archive, then find and summarize two literacy narratives housed in its collections. These stories reflected, problematized, and enhanced the literacy theory we covered. For example, Suzanne Keen’s “Not Allowed to Read Until First Grade” (2009) demonstrated the “sponsorship” and “gatekeeping” concepts that I found so interesting, while highlighting the tension between formal literacy instruction and non-academic literate practice so prevalent in Rose’s Lives on the Boundary. “Bronson Farr’s Literacy Narrative” (Farr, 2009) further illustrated the issues raised by Rose’s text, describing one student’s experience of being underprepared to meet the demands of a rigorous new academic institution, and the frustration that can result when schools are unable (or refuse) to address limitations imposed by circumstances outside the classroom. In these narratives, I saw the theory we discussed in class as it played out in people’s lives. I was beginning to understand how such narratives could help scholars construct an understanding of literacy. As a result, my understanding of literacy studies as a whole is inextricably linked to the DALN.

As Harker and Comer find in “The Pedagogy of the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives,” when teachers use literacy narratives in the manner described above, the narratives become an “invention activity” in which students use the stories as examples to generate their own literacy narratives (2015, p. 73). This was somewhat true in my experience, as a major assignment in “Community and Literacy” asked us to compose a literacy narrative with the option to upload it to the DALN. Reflecting on my literate practices empowered me as one who understood literacy theory through the lens of my own unique experience. For the assignment, I revisited a time in my life that I had not previously connected to my literacy development as it didn’t adhere to sites of literacy learning in a traditional sense. I see now how such an assignment complements pedagogies that empower students, as it “positions [them] as experts” and “agents in future learning” (Harker & Comer, 2015, p. 66). The literacy narrative assignment recognized the critical role that this experience played in my life, allowing me to apply new approaches to the theory we covered in class. It confounded everything that I had known about learning models up to this time, and I was eager to pursue the course in my new role(s).

In their survey of DALN pedagogies, Harker and Comer (2015) discuss the diverse ways that teachers introduce the DALN to their students, outlining the various relationships that undergraduates might have with the archive. Depending on course goals, students might delve into the DALN’s records, compose and upload their own literacy stories, or even gather narratives to contribute to its collections. Bill’s approach in “Community and Literacy” took advantage of several of these opportunities, positioning students differently in relation to the archive throughout the semester. The DALN did not just serve as an inspirational site for my literacy narrative; it allowed me to take on identities that I had never before inhabited as a student. To borrow terms used by Harker and Comer, I acted as “audience,” “publisher,” and “curator” (2015, p. 71).

Escaping the Classroom (with Help from the DALN)

In the final weeks of the semester, Bill shifted focus from using the DALN as a space for reading and contributing, repositioning the archive as a base from which we imagined conducting research. As we read and summarized selected narratives, we also considered what we found most interesting about them and drafted potential questions for the author. We studied the sample interview questions provided by the DALN and took turns interviewing each other in class. From very early on we considered what it might mean to gather information from someone, to probe for answers and follow promising threads in conversation. Asking questions of others also helped me turn a critical eye inward, questioning my own experience to identify and expand on a crucial aspect of my literacy development that I had never before given credence. These activities also prepared us for what came next: the final assignment, a collaborative fieldwork project that required us to engage with people outside of our comfortable classroom community. We were to solicit their literacy stories, relate them to an aspect of theory we had learned thus far, and hopefully upload them to the DALN.

The fieldwork project surprised me, as it differed from the long-established pattern of all my other English courses. Over the years, I had come to expect the dreaded end-of-semester “Research Paper.” Summarized simply, this kind of “research” is a foray into secondary sources in which students pull quotes from established authors to serve as evidence for a thesis that they have long-since developed. Many have argued that this traditional model is antiquated and ineffective (Bean, 1996; Fister, 2011; Grobman, 2007 & 2009; Hayden, 2015; McDorman, 2004; Shafer, 1999). Instead, they advocate for assignments that invite students to conduct authentic research that more closely resembles what is actually done by scholars in the field. This alternative model requires that student research be driven by genuine inquiry, often focused largely on primary sources. It encourages them to become producers rather than consumers of knowledge. “Community and Literacy’s” Field Work Project did just that. It asked students to consider the theory we had learned in class; but first and foremost, it required that we actively consider theory in relation to primary data that we gathered first hand.

Not only did the DALN serve to guide me through literacy theory, it also provided a guide for conducting interviews, a space for me to consider what questions I might ask and what results might look like, as well as examples of what form the narratives might be recorded in (i.e. text, video, audio, comic). From the beginning, the DALN’s collaborative nature inspired me. Its choice to position contributors as “participants” rather than “subjects” supports the notion that these individuals hold expertise in their own literate experience. They possess the same agency and importance as the researcher, if not more, and the interview space reflects that. This principle impacted me deeply, and I resolved to interact with my participants on an equal playing field. As an English major who had only ever written “traditional” printed papers before, I was also confronted with the fact that these records live online, as does much of the research that draws from them. The DALN’s digital landscape opened a wide range of possibility that print simply could never afford. I began to consider how I might use video recordings to more authentically capture and represent my participants’ literacy stories in their own voices. As experts, my participants would (and should) be able to speak for themselves. My role was one of invitation and curation rather than translation and control. Thus, the DALN sculpted my nascent understanding of research methodologies, forming a foundation present in my research practices even today.

That term, I was fortunate to sit between two brilliant fellow classmates with similar drives and interests in the course to my own, and we decided early on that we would work together on the collaborative project. We discovered that we all possessed similar interests and potential research questions. While the course’s initial aim to partner with local schools and libraries hadn’t come to fruition for a host of reasons, I found that I wasn’t as interested in working with that population as I had once thought. Rather, as a result of the reading we had done throughout the semester, my partners and I were more interested in issues of academic literacy and the university’s role as a gatekeeper, especially for at-risk student populations.

Access ultimately became the deciding factor in our project design, as one of my partners worked as a registrar for the University of the Arts in Philadelphia (UArts) and maintained a close friendship with their head of International Student Services. We focused our research on English Language Learning (ELL) students entering UArts, and were granted access to a Thanksgiving luncheon that was thrown for the university’s international student population. We arrived equipped with a video camera, a stack of consent forms, and a long list of interview questions. These questions were drafted based on examples we lifted from the DALN, Bill’s input, and a broad guiding research question: “How do social and academic models affect the acquisition of English language literacy among international university students?”

On the day of the interviews I was extremely nervous, but hours spent reviewing narratives on the DALN and practicing in class paid off. Hunched together in a cold stairwell to escape the noise of the luncheon, the sounds of a nearby musical rehearsal echoing around us, my partners and I met one by one with six participants. We each took turns operating the camera, recording notes, and asking questions. The conversation was stilted at first, and the language barrier did nothing to ease the situation, but as time went on we settled into a comfortable rhythm. Just as in our initial DALN narrative summaries, the participants shared things that sparked our interest, and questions began to lead organically from one to the next. Gradually, the interviews became less like formal meetings and more like easy conversation. We noticed common threads running through each of their stories. Each participant recounted tales regarding social media’s influence on their English and academic literacy, as well as the importance of social relationships and the “extracurricular” (Gere, 1994). At the end of the day my partners and I were exhausted, but based on these recurring topics we had an idea of how to make sense of what felt like a mountain of information.

Ultimately, we decided that a “traditional” paper would not be the most effective way to convey our participants’ stories or our conclusions, nor would it appropriately reflect what we had learned in “Community and Literacy” as a whole. Time spent on class assignments such as personal literacy narratives and daily literacy logs taught us the value of recognizing the expertise gained through unique experience, and as a result, we wanted to preserve the voices of our participants as best we could. The last thing we wanted to do was delegitimize their perspectives by speaking for them. Additionally, we knew that many of the records on the DALN blended multiple modalities, and we wanted to maintain that rich and eclectic method of sharing ideas. Eventually, we decided to create a web page using Weebly (see Figure 1).

This format allowed us to incorporate images of our participants, interspersing our own text with video clips of the students telling their own stories (see Figure 2). We were able to maintain the integrity of our participants’ voices while also piecing together their experiences as primary data, demonstrating what we perceived to be important connections and deviations between them. For the first time, I was producing knowledge.

In “Community and Literacy,” I stepped into the roles of “audience,” “publisher,” and “curator” for the first time (Harker & Comer, 2015, p. 71). I read and reflected on literacy narratives that both supported and questioned the theory we discussed in class. I explored a private (and somewhat painful) part of my life, examining its impact on my relationship with literacy, writing my narrative, and uploading it anonymously to the DALN. I even ventured to a new university in an unfamiliar part of the city, turning the camera around to learn the stories of others and then contribute them back to the archive. Engaging in this multi-faceted experience of the DALN brought me closer to conducting real research than I had ever been.

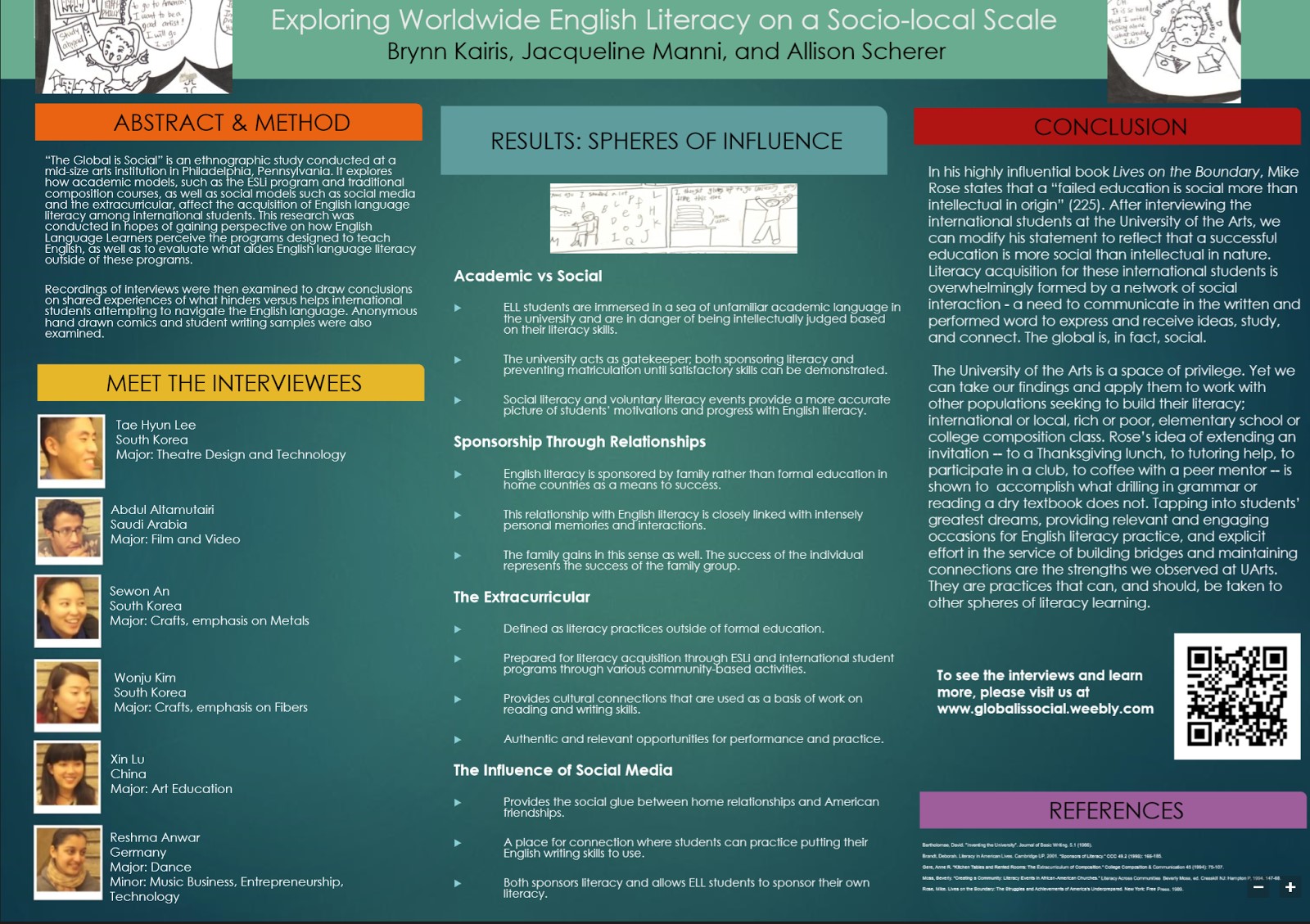

Bill suggested that my partners and I propose our project for the 2014 Conference for College Composition and Communication, and we were ecstatic to be accepted for the Undergraduate Research Poster Session. I was enthusiastic to learn more about literacy studies, and curious as to whether this could be a viable career move. While I once dreamed of teaching high school English, I gradually realized that such a career might never deliver the kind of learning and fulfillment that I had experienced that Fall. With this in mind, when Bill invited the three of us to take part in his graduate “Research Methods in Composition and Literacy” course, I accepted.

II. Spring 2014: Researching with the DALN

Brynn

From Curation to Analysis

Archives encourage student learning through a range of activities, including archiving itself as students consider, collect, and curate materials. They also enter the space of the archive as a site for research with specific methodologies. During my initial encounter, I turned to the DALN as a site for exploration, connecting theory to practice in the lives of various authors, myself included. The DALN also became a site for collection and curation as I practiced modes of soliciting, gathering, and representing data. While I was thrilled to engage in new ways of learning, I was still ensconced in my role as a student. I had yet to consider how my work could be situated outside the immediate goals of the classroom.

During the second semester I took Bill’s graduate course, “Research Methods in Composition and Literacy,” and experienced a dramatic shift in my relationship to the DALN (See Appendix G for course syllabus). I embraced the archive as a site for research, learning how to draft a viable research question, develop a methodology drawn from best practices, and enact that methodology using materials from the archive to arrive at a conclusion. Finally, I shared my work with others beyond my classmates and professor (more discussion on that later).

This experienced with the DALN unsettled previous notions about what it meant to “do research.” In the past, I learned that “research” meant picking a topic that I found vaguely stimulating, reading several related pieces of scholarship, and then reporting what they said. In this course, I learned that research is driven by genuine inquiry, informed by theory, and governed by methodology. Most importantly its primary goal is the creation, not recirculation, of knowledge. Diving deeper into the DALN, I truly became a “researcher.”

As a second semester junior, I felt equal parts excitement and terror at the thought of joining a graduate-level research methods course. I didn’t know what to expect from the syllabus, the assignments, or the other students. However, I was certain of one thing: my initial experiences with the DALN had awakened a hunger to know more, dig deeper, and figure out how to really “do” research. While I had successfully completed the fieldwork project in “Community and Literacy” and would present a poster with my partners at a national conference (see Figure 3), I had much to learn about being a researcher. Rather than acting as an undergraduate student completing a project to satisfy a course requirement, I realized that I wanted to become a member of the writing studies discipline. To me, this meant conducting research and participating in authentic academic discourse. Most importantly, I wanted to discover and share knowledge, and a research methods course seemed to offer the practical skills required for success.

Bill anchored the course with a five-week unit on archival research. We read Ramsey et al.’s Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition (2009), supplemented by readings from scholars such as Gold (2012), Blakeslee and Fleischer (2007), Buehl, Chute, and Fields (2012), and others. The course itself did not incorporate the DALN directly, but I encountered these new theories through the lens of my experience the previous Fall. The course showed the archive in a new light, and I considered what it might mean to approach the DALN as a research space. Rather than using the DALN for a series of invention activities or a model for conducting interviews, I saw the archive as data. A “Practitioner’s Report” loomed at the end of the unit. I knew I would have to choose an archive, exploring and reflecting on it systematically based on the concepts we had covered in the course. I would have to imagine what shape conducting research in that space would take.

While my classmates chose a range of physical archives that suited their interests, I just couldn’t shake the DALN. I had the distinct feeling that I hadn’t overturned all of the digital rocks worth exploring. With a new understanding of archival research beginning to take root, I began probing. Eventually, I found the DALN’s Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Contributors collection.

From Analysis to Dissemination

Susan Wells (2002) calls “resistance” the first “gift” of the archives; this resistance kept drawing me back. I was discovering that archives resist our “first thoughts,” rarely delivering what we want, or even expect, to find. Archives reject the neat and tidy boxes in which we struggle to package our research; they “refuse closure” (p. 58). Wells describes many scholars who “have stories of loose ends they could not leave alone” (p. 58). The DALN is no different, and the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Contributors collection became the thread that I could not let go. I was fascinated by the resistance in the narratives themselves—the rejection of prescriptive labels and understandings of what constitutes “literacy,” as well as attempts to define, categorize, or generalize. Even the myriad modalities comprised of blended audio and video narratives including American Sign Language, text, and spoken English challenged my expectations. I was hooked.

Something about the organized chaos of archival work appeals to me. Bill frankly shared his own research process with the class, recounting moments of tension and frustration as well as breakthrough. Wendy Hayden writes about teachers making “invisible” methodologies visible to students, acknowledging that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to research (2015, p. 404). Bill’s openness about his own methods, as well as my initial encounters with the DALN, led me to embrace the “messiness” of archival work early in my research career (Rickly, 2007).

Even as the course moved on to address empirical and ethnographic research methods, I knew that I would return to the archives to complete my final Research Proposal Project. For the assignment, we were asked to identify a research problem, draft a research question, and conduct preliminary research to justify the need for more knowledge addressing the problem. I found it increasingly difficult to conduct only “preliminary research” in the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Contributors collection; the data pulled me in deeper and deeper. My final proposal included an extended section of preliminary data, in which I employed grounded theory methodology (Charmaz, 2008; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) to code two literacy narratives and identify emergent themes regarding the resistant nature of D/deaf writing. When I used a similar methodology earlier that year to complete the Field Work Project in “Community and Literacy,” discovering similar topics in participants’ stories and using those similarities to answer a research question, I didn’t know that the approach had a name let alone a mass of theory supporting it. Now, I was able to use my new knowledge about methods to produce a more mindfully designed research project.

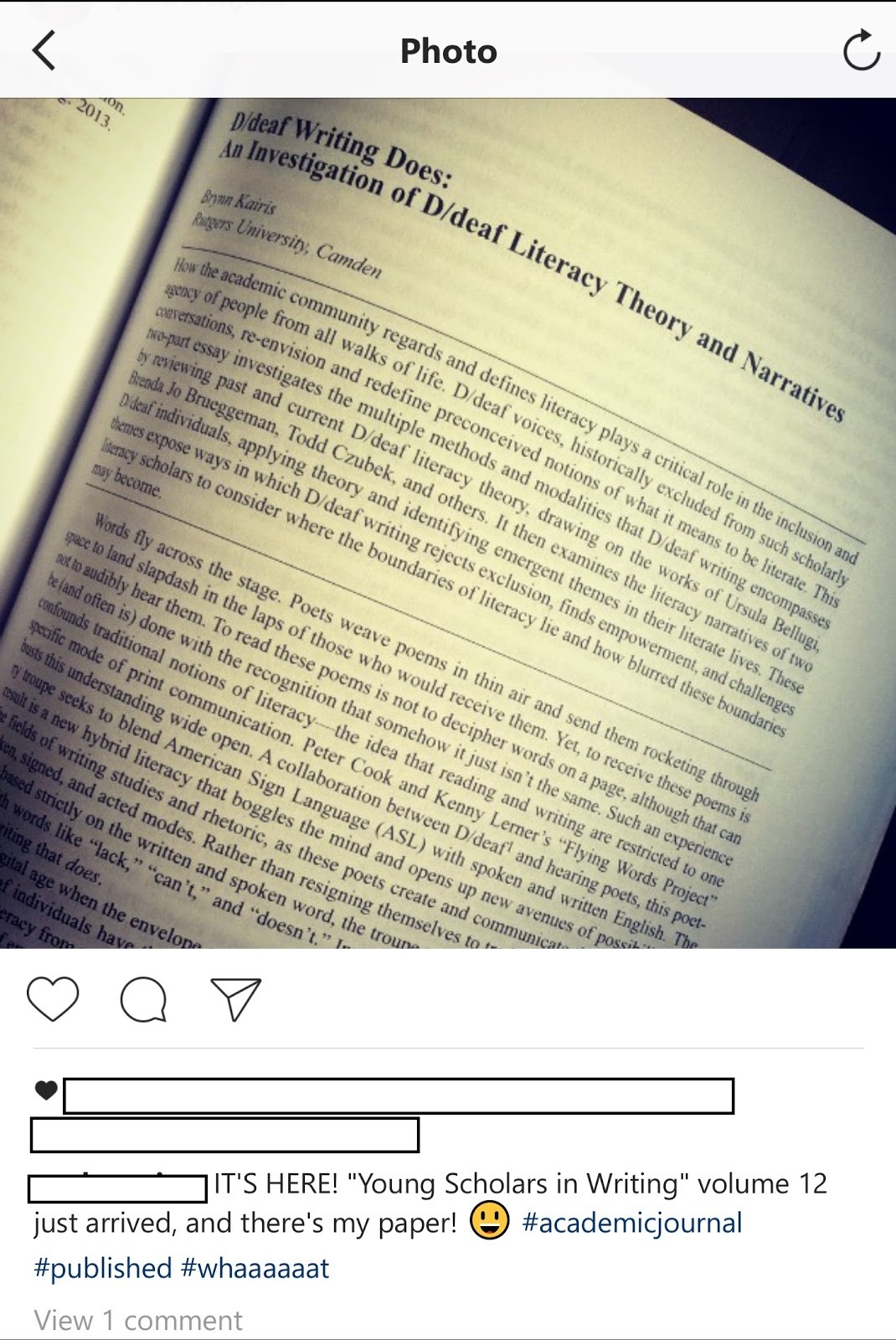

Bill felt that my research was strong enough to revise the proposal into a full length article for submission to Young Scholars in Writing. He guided me through re-purposing the document for publication (something I had never done before), and to my delight it was accepted for their Spring 2015 volume (see Figure 4). I had achieved one of my initial goals, completing what I now recognize as a crucial final step for students to see themselves as “researchers”—sharing my work with others.

Laurie Grobman advocates for the recognition of undergraduate researchers as novices on a “continuum of authority” as opposed to unskilled outsiders to the discipline (2009, p. 178). One of the ways that we might do this is providing spaces such as Young Scholars in Writing, which act as entrance points to the academic discourse community. Acknowledgement encourages students to own the knowledge they gain through research and experience. As a public project, the DALN expands on these beliefs, positioning contributors as authorities in their own right. Those who upload their literacy narratives to the DALN claim agency, myself included. Their individual experiences with literacy are valuable, as their histories develop unique perspectives. Not only does the DALN serve as a place where contributors stand as experts, it is a space where these experts deposit a wealth of information. In turn, this information becomes data used by both established literacy scholars and those just learning how to do research. It provides the tools and access that are necessary to develop and address research questions. Finally, it becomes a place where those researchers might then contribute data, publishing both what they’ve gathered from participants as well as their own stories. This versatile archive served as a space where I could inhabit multiple identities over the course of a single academic year, using the archive as an “audience,” “curator,” “publisher,” and finally, “researcher.”

Bill

Initially, I hadn’t planned to feature the DALN in my course on research methods. But a positive experience with the DALN prompted me to leverage its potential. Until then, I hadn’t taught any type of research methods; I thus felt sometimes like a poseur. I would read pieces in CCC, Written Communication, or other journals and think, “I cannot do what many of my colleagues do.” More importantly, I had come to believe that my limitations as a researcher was holding back my own students. Having resisted rigor and mess in working with qualitative data, I took the advice of a friend, Jonathan Buehl, to venture into unfamiliar territory. Indeed, Jonathan’s co-written piece, “Training in the Archives: Archival Research as Professional Development,” (Buehl, Chute, & Fields, 2012) demonstrated the pedagogical value of archival research. The course I taught in Spring 2014 was largely modeled on one Jonathan had taught at The Ohio State University. It began with archival research and moved to other ways of working with verbal data.

Since students did not engage in full research projects but only practiced methods to which they were introduced, they submitted several “practitioner” reports leading to a proposal for a substantial research project in the future. In the first unit, students compiled a research log that reflected initial encounters with a physical or digital archive. Of 15 students in the course, including three undergraduates who had taken “Community and Literacy” in Fall, only Brynn drew on prior knowledge of the DALN to prepare her research log with an emerging focus on literacy and deafness, inspired by two texts in the edited collection Stories That Speak to Us (2013): “Articulating Betweenity: Literacy, Language, Identity and Technology in the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing Collection” (Brueggemann & Voss, 2013) and “Accessing Private Knowledge for Public Conversations: Attending to Shared, Yet-to-be-Public Concerns in the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing DALN Interviews” (Clifton, Long, & Roen, 2013). However, all students would become acquainted with the DALN through the second practitioner report, on “empirical” research. The assignment asked students to work in small groups coding and analyzing several literacy narratives located on the DALN. It required that they develop a testable hypothesis based on their analysis and draft a one-page proposal arguing for the significance of a larger project (See Appendix H for assignment outline). This small exercise was the only collective encounter with the DALN that semester, but it proved to be a substantive one given our efforts to unpack the implications of using digital materials as a site for research, for employing particular methods of analysis to engage verbal data, and for the engaging the ethical dimensions of research involving human subjects.

Everyone thus benefitted from the DALN as a near-at-hand resource, one that welcomed both developmental exercises as well as more systematic inquiry such as Brynn’s undertaking. Her research arc began with the exploratory archival effort and culminated in a proposal, a substantial sketch of a hypothetical project. Except in this case the quality of the research was so strong that I encouraged Brynn to press on and to recast her preliminary findings into a submission to Young Scholars in Writing. It didn’t surprise me that Brynn’s essay, “D/deaf Writing Does: An Investigation of D/deaf Literacy Theory And Narratives” would be published in next year’s volume (2015). In her piece, Brynn brings scholarship on literacy and deafness (Ursula Bellugi, Brenda Jo Brueggeman, Todd Czubek, and others) to bear on her own encounters with submissions to the DALN. In particular, as Brynn states in her abstract, the essay, “examines the literacy narratives of two D/deaf individuals, applying theory and identifying emergent themes in their literate lives. These themes expose ways in which D/deaf writing rejects exclusion, finds empowerment, and challenges literacy scholars to consider where the boundaries of literacy lie and how blurred these boundaries may become” (Kairis, 2015, p. 45).

Scripted Postscript: Forever Living DALNgerously

Bill: I have been fortunate to mentor the undergraduate research of three students whose work appears in Young Scholars in Writing. In the first case, as noted above, my student Marc Hummel (2011) engaged in self-sponsored participant observation at a store-front literacy center in Philadelphia and was able to apply concepts from genre theory to articulate the uptake of literacy among the young people he worked with as an after-school volunteer. In a second case, Natali Midiri (2012) brought rhetorical theory to bear in an analysis of human rights rhetoric. What stands out in Brynn’s case, the third instance, is a through line of a budding research agenda as an affordance of the DALN (2015). That agenda continues here in this our collaborative account.

Of course, there’s a risk in this profile of singling out the exceptional over the less dramatically transformational. Hence, I wish to underscore that the DALN served as a powerfully generative resource for many of my students who didn’t take classroom-based research activities to the next level through publication. The undergraduates in “Community and Literacy” and my students in the graduate-level course in research methods were exposed to new and generative ways of thinking about their identities as discoverers of and contributors to knowledge. Before that “year,” I hadn’t sufficiently appreciated the pedagogical value of archives as sites for learning and research or really understood the full range of activities (i.e., collection, curation, analysis) afforded by archives.

Less clear at the time was how this turn to literacy studies in my courses, centered in the laboratory of the DALN, was for me an act of reinvention. Prior to this year, I avoided anything that involved the IRB approval process. In both courses that year, however, my students and I learned together the process; it wasn’t long until I was sponsoring and conducting research that involved data collection in human subjects research for several ongoing projects. Indeed, insights arising in that year inspired me to apply to the Dartmouth Seminar in 2015 for an immersive experience in research methods in writing studies—a mid-career move that amounted to hitting the reset button. Without the DALN as a catalyst, I doubt that I’d be on the path I’m now on as a teacher, a scholar, or writing program administrator. I likely would not be undertaking an IRB-approved research study (with Brynn) that involves collecting written texts and recording interviews with subjects were it not for the fieldwork in literacy narratives and inspired and guided by the DALN. And I suspect I wouldn’t be directing first year writing in a program centered on experiences of genuine research for every student through fieldwork, archival investigations, and analysis of primary data. My “year of living DALNgerously” gave me confidence to take on these new challenges.

Brynn: As “Community and Literacy” ended in Fall 2013 I questioned long-held aspirations, wondering if I might pursue literacy studies and a career in higher education. After “Research Methods” in Spring 2014, the choice was easy. Encountering the DALN forced me to reconsider what I thought I knew before transferring to Rutgers-Camden, exposing me to new ways of thinking about literacy, learning, and research. There was no going back. I decided to pursue a masters in English with a concentration in Writing Studies.

First, I needed to finish my undergraduate degree. During the next academic year, I continued working with the DALN and honing my research skills. In 2014, I attended the Naylor Workshop on Undergraduate Research in Writing Studies hosted by York College. There I met other young scholars during an intense weekend of mentorship, workshops, and presentations. At Naylor, I developed a plan to both extend and streamline my work with the DALN’s D/deaf literacy narratives, attending to lingering questions I hadn’t answered in my initial round of research. I was honored to present results from that expanded project as a research poster at CCCC 2015.

Bill: I have completed a second year as my department’s writing program director, having recently unrolled new syllabi for our two-course sequence. The second course, in particular, centered on literacy and research, marks me as a student of the DALN. In this course, students begin with a literacy narrative, and instructors introduce students to the DALN and even encourage students to contribute. In doing so, we wish for students to understand their own lives through a framework of literacy. But we also want them to reach this understanding aware that their stories are part of a larger story reflected in the kaleidoscopic vision of the DALN. And that story includes the existence of the DALN itself as a repository and an agent of literacy. Indeed, our course text, Everyone’s An Author (Lunsford et. al., 2016), offers a multimodal framework for composing consonant with expectations and protocols of the DALN. Indeed, the DALN serves as a source for legitimizing and normalizing the multimodal approach to literacy that guides our writing program. For example, rather than write a traditional “research paper” drawing heavily on library-vetted secondary sources, students in our program are expected to conduct primary research (e.g., interviews, surveys) and encouraged to produce texts in a variety of academic and civic genres. Increasingly, as a program culture takes root, our writing instructors turn to archives like the DALN and others as sites for research.

For us, the DALN is an ambassador for curricular innovation. By its very presence, the DALN invites contrastive models of education and engagement from those anchored in paradigms of skill building. It invites play, active-learning, curiosity. It continually reminds scholars and students of the large and vibrant sphere of literacy against which more narrow models may be placed. The DALN thus serves as a useful reminder to anyone who teaches composition (or directs a writing program) that our sponsorship and stewardship of literacy is necessarily partial. Of course, so too is the DALN. It argues fo, and enact, a vision of literacy that counters dominant “deficit” models on which the industry of higher education depends (Alexander, 2011; Bryson, 2012; Graff, 1979). And the DALN offers the broader field of English studies new ways of imagining, arguing for, and implementing an integrative vision—one that resists, even confounds, binaries on which our so many of our intramural differences depend: reading/writing, print/digital, academic vs. civic, expert vs. amateur.

I cannot quite imagine the writing program I would be directing in the absence of encounters with the DALN. Perhaps it would be very similar. I can say, however, that a “year of living DALNgerously” welded into place a commitment to a kind of engaged learning at once more skeptical of grand literacy narratives, especially those that tell of the uplifting force of the academy (including my profession of rhetorical paradigms for composition pedagogy) and more embracing of direct, daily encounters with literacy as sites of opportunity and, yes, recalcitrance. This essay, then, is a kind of literacy narrative for me. It risks being a grand narrative of progress by embracing opportunity even as I acknowledge factors of recalcitrance that may have impeded progress over the years. Fittingly, it is a collaborative effort because my students and their embrace of literacy as an empowering force and subject matter continue to inspire me to grow as a scholar and educator.

Brynn: Now, having completed my M.A. in English–Writing Studies and spending two years working as a FYC teacher at Rutgers-Camden, I acknowledge the role of the DALN in shaping my approach to research as well as pedagogy. Its influence became apparent as I taught the course on literacy and research that Bill describes above. In addition to conducting interviews and surveys, I asked my students to explore digital archives, including the DALN. These sites provided easy access for them to engage with primary research materials, a new experience for most. The students who chose to further engage with primary data and delve into the archives for their final projects expressed greater pride and connection to their work. In a reflection, one student even began to imagine how his research might develop through future coursework, envisioning a time when he might pursue his research question at the graduate level.

I appreciate Bill’s description of learning alongside his students. Even as I lead my own students through encounters that were new to me only a few years ago, I find myself continuing to grow as a researcher. As we investigate the DALN and other archives, I’m reminded of the opportunities for discovery that so entranced me in my junior year.

The archive, however, continues to resist and refuse. Archival pedagogies often complicate understandings of “research” and “scholarship” that students carry into the classroom. As students develop questions and sift through materials they must reconsider their roles as learners and producers of knowledge. When they compose literacy narratives of their own, they step into the role of “expert”—often uncharted territory. They reconsider assumptions about the power dynamics of various methodologies, including issues surrounding representation and agency. Much of this is new. Some may find it unsettling and respond with resistance of their own. In Bill’s discussion above, he raises concerns regarding the ethics of requiring students to submit their narratives to the DALN. While the DALN provides opportunities to inhabit new roles, we must ask whether a pedagogy informed by the spirit of the DALN will allow for that resistance. If students truly own their experiences with literacy and scholarship, then they ultimately have the choice where, and with whom, to share that work. Perhaps a DALN-based pedagogy, then, is one of invitation rather than prescription, giving students the opportunity to enter the archive, to embrace archival work in all its messiness while trying on the various identities that such work allows.

The DALN continues to sculpt my own development as a scholar. While my current research does not deal directly with the DALN, I carry what I first learned about research through the archive with me. These initial encounters gave me the skills I needed to carry out more complex projects, including developing methodologies, obtaining IRB certification, conducting interviews, and coding writing samples. I owe these abilities, as well as the confidence to accept myself as a scholar, researcher, and teacher, to my “year of living DALNgerously.”

References

Alexander, K. P. (2011). Successes, victims, and prodigies: “Master” and “little” cultural narratives in the literacy narrative genre. College Composition and Communication, 62(4), 608-633.

Bartholomae, D. (1986). Inventing the university. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4-23.

Barton, D. (1994). Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of the written language. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Bean, J. (1996). Engaging ideas (2nd ed.). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Blakeslee, A. & Fleischer, C. (2007). Becoming a writing researcher. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brandt, D. (1998). Sponsors of literacy. College Composition and Communication, 49(2), 165-185.

Brandt, D. (2001). Literacy in American lives. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Brueggemann, B. J. & Voss, J. (2013). Articulating betweenity: Literacy, language, identity, and technology in the deaf/hard-of-hearing collection. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Bryson, K. (2012). The literacy myth in the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Computers and Composition, 29, 254-268.

Buehl, J., Chute, T., & Fields, A. (2012). Training in the archives: Archival research as professional development. College Composition and Communication, 64(2), 274-305.

Charmaz, K. (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In S. N. Hess-Biber & P. Levy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp. 155-170). New York: The Guilford Press.

Clifton, J., Long, E., & Roen, D. (2013). Accessing private knowledge for public conversations: Attending to shared, yet-to-be-public concerns in the Deaf and hard-of-hearing DALN interviews. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (1997). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Cushman, E., Kintgen E. R., Kroll, B., & Rose, M. (Eds.). (2001). Literacy: A critical sourcebook. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Selfe, C. L. & The DALN Consortium. (2012). Narrative theory and stories that speak to us. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories that Speak to Us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Diamond, J. (1999). Guns, germs and steel: The fates of human societies. New York: W.W. Norton.

Farr, B. (2009). Bronson Farr’s literacy narrative. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/3d28b6ff-cedd-43e0-9c92-6e731040725c

Fister, B. (2011). Why the “research paper” isn’t working. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/library-babel-fish/why-research-paper-isnt-working

FitzGerald, W. (2012). Spiritual modalities: Prayer as rhetoric and performance. University Park, P.A.: Penn State UP.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What videogames have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment (CIE), 1(1), 20-20.

Gere, A. R. (1994). Kitchen tables and rented rooms: The extracurriculum of composition. College Composition and Communication, 45(1), 75-92.

Glaser B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Gold, D. (2012). Remapping revisionist historiography. College Composition and Communication, 64(1), 15-34.

Goldblatt, E. (2005). Alinsky’s reveille: A community-organizing model for neighborhood-based literacy projects. College English, 67(3), 274-295.

Goldblatt, E. (2007). Because we live here: Sponsoring literacy beyond the college curriculum. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Goody, J. (1987). The interface between the written and the oral. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graff, H. J. (1979). The literacy myth: Literacy and social structure in the nineteenth-century city. New York: Academic Press.

Graff, H. J. (1987). The legacies of literacy: Continuities and contradictions in western culture and society. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Grobman, L. (2007). Affirming the independent researcher model: Undergraduate research in the humanities. Council on Undergraduate Research Quarterly, 28(1), 23-28.

Grobman, L. (2009). The student scholar: (Re)negotiating authorship and authority. College Composition and Communication, 61(1), 175-196.

Hayden, W. (2015). “Gifts” of the archives: A pedagogy for undergraduate research. College Composition and Communication, 66(3), 402-426.

Harker, M. & Comer, K. B. (2015). The pedagogy of the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives: A survey. Computers and Composition, 35, 65-85

Havelock, E. A. (1963). Preface to Plato. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Heath, S. B. & Street, B. (2004). On ethnography: Approaches to language and literacy research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hummel, M. (2011). Community writing centers and genre literacy. Young Scholars in Writing, 9, 58-63.

Kairis, B. (2015). D/deaf writing does: An investigation of D/deaf literacy theory and Narratives. Young Scholars in Writing, 9, 45-53.

Keen, S. (2009). Not allowed to read until first grade. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/49edb3b5-33ef-477a-8a66-1667609b7ae9

Kirsch, G. E. (2008). Being on location: Serendipity, place, and archival research. In G. E. Kirsch & L. Rohan (Eds.), Beyond the archives. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Lunsford, A., Brody, M., Ede, L., Moss, B. J., Papper, C. C., & Walters, K. (2016). Everyone’s an author (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

McDorman, T. (2004). Promoting undergraduate research in the humanities: Three collaborative approaches. Council on Undergraduate Research Quarterly, 25(1), 39-42.

Midiri, N. (2012). The stylistic effects of human rights rhetoric: An analysis of U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s 2011 LGBT human rights speech. Young Scholars in Writing, 10, 97-104.

Moss, B. (1994). Creating a community: Literacy events in African American churches. In B. Moss (Ed.), Literacy across communities (pp. 147-178). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Olson, D. R. (1996). The world on paper: The conceptual and cognitive implications of writing and reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Routledge.

Pratt, M. L. (1999). Arts of the contact zone. In D. Bartholomae & A. Petrosky (Eds), Ways of reading (5th ed.). New York: Bedford St. Martin.

Ramsey, A. E., Sharer, W. B., L’Eplattenier, B., & Mastrangelo, L. (2009). Working in the archives: Practical research methods for rhetoric and composition. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Rickly, R. (2007). Messy contexts: Research as a rhetorical situation. In D. N. DeVoss & H. A. McKee (Eds.), Digital writing research: Technologies, methodologies, and ethical issues (pp. 377-397). New York: Hampton Press.

Rose, M. (1989) Lives on the boundary: The struggles and achievements of America’s underprepared. New York: Free Press.

Scribner, S. & Cole, M. (1981). The psychology of literacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Selfe, C. & Hawisher, G. (2004). Literate lives in the information age: Narratives of literacy from the United States. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Shafer, G. (1999). Re-envisioning research. The English Journal, 89(1), 45-50.

Ulman, H. L., DeWitt, S. L., & Selfe, C. L. (Eds.). (2013). Stories that speak to us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Wells, S. (2002). Claiming the archive for rhetoric and composition. In G. A. Olson (Ed.), Rhetoric and composition as Intellectual work (pp. 55-65). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

What is a literacy narrative? (2012). Retrieved from https://thedaln.wordpress.com/daln-resources/

Yancey, K. B. (2009). Writing in the 21st Century: A report from the National Council of Teachers of English. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.