The DALN as Mentor Text: Empowering Students as Literacy Agents

ALICE MYATT & GUY KRUEGER

ABSTRACT

The authors encourage writing teachers to view the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN) as a collection of mentor texts and a repository of rich resources, expanding students’ understanding of what a literacy narrative does or what literacies are while empowering students to communicate authentically about their own literacy journeys. In this way, the narratives in the DALN provide teachers with mentor texts—models—they can use to help students understand how different types of literacy can inform their own narratives. Instead of privileging literacies of power (particularly white, and almost certainly middle- to upper-class), the DALN allows students to see literacy as “more ‘participatory,’ ‘collaborative,’ and ‘distributed’ in nature than conventional literacies” (Lankshear and Knobel, 2007, p. 9). At the same time that the DALN provides mentor texts for students, teachers who become familiar with and use the DALN archives, especially those new to or inexperienced with teaching literacy narratives, are encouraged to recognize and move past tendencies toward taking a deficit approach (Rose, 1985; Izarry, 2009) and instead adopt a stance similar to that advocated by Mike Rose (1985), who encouraged writing teachers to embrace “the full play of language activity” by providing access to “the academic community rather than sequestering students from it” (p. 358).

***

Introduction

Our chapter engages with themes of literacies and narrative writing, with such writing acting as an underlying foundation that fosters students’ awareness of the complexities embedded within literacy studies by crafting narratives that engage with their own journeys and experiences. In discussing how the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN) may serve as mentor texts in the composition classroom, we draw on various frameworks that have informed our engagement with and appreciation for the narratives found there.1

We describe how we use the DALN in the classroom to engage students in literacy practices, drawing on the scholarship of multiple literacies (New London Group, 2000), literacies and power dynamics (Alexander, 2011; Daniell, 1997; Graff, 1979), multimodality (Kress, 1997), self-efficacy (Bandura, 1994), funds of knowledge (or FoK) (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992; Velez-Ibanez & Greenberg, 1992), and the application of FoK to the role of mentor texts in the composition classroom (Newman, 2012). Specifically, we use narratives from the DALN as mentor texts from which both students and teachers learn to appreciate the multiple literacies we gain within our communities of practice, enabling students to move beyond simplistic engagement with literacy narratives as stories of how they learned to read or write, to more sophisticated and complex narratives that present rich tapestries of diverse knowledges.

We also describe the value of the DALN as a repository of rich resources for teachers that not only expand students’ understanding of what a literacy narrative does or what literacies are but also empower students to speak authentically about their own journeys and give them more literacy agency. In this way, the narratives in the DALN provide teachers with resources they can use to help students understand how different types of literacy can inform their own narratives, and teachers are given the pedagogical support to move beyond a deficit model of teaching that is structured to address what students lack, not what they have gained from their lived experiences, regardless of whether such are positive, negative, tragic, or mundane (Rose, 1985; Izarry, 2009). In contrast to the deficit model, when teachers encourage students to reflect and compose in focused ways about the entirety of experiences in their lives, teachers are giving all students—not just a privileged few—the foundation to recognize and value their own histories.

As teachers of composition, we know that a major investment of our time and energy is to encourage students to view themselves as individuals who are empowered to speak and write with authentic voices about their lived experiences. Yet our students often come into our classrooms having been stereotyped into deficit models—lacking in agency. The imposition of deficit models of ability on such students, who are often situated within minoritized communities or populations, engenders within them a lack of confidence. Often, they may feel that they have nothing genuine to contribute to conversations about literacy or literacies. Such feelings may stem, in part, from the awareness that their own histories of literacy fall outside mainstream (Lesley, 2008), often reified, narratives that are used as models for what an “excellent” literacy narrative is or does. Thus, they become constrained by the invoked power characteristic of reification, whether of literacy or other abilities.2

One method among others that supports the development of these students into agents of their own literacy is to point to existing literacy narratives that situate difficult (Becker, 2014) or dark (Zipin, 2009) knowledge and experiences as among legitimate literacies. The DALN has a number of entries in which people from a variety of backgrounds discuss how their often complex and difficult journeys shaped their own literacies. In such situations, students can learn to view what they often think of as “outsider” experiences as real and meaningful learning (Alexander, 2011). For example, students may have developed or sharpened strong critical-thinking skills due to growing up in a dangerous neighborhood or having lived through a traumatic event that thus altered behaviors. It is indisputable that meaningful education happens both in and outside of school settings, but too often the lives and learning experiences of marginalized students are ignored in traditional academic institutions, despite a growing movement of late in which lived experiences or prior learning counts as college credit at a number of institutions.3Our research and teaching, and thus this chapter, have been guided by the desire to help students embrace their own unique literacies and value them as part of a larger context of learning. Borrowing from Newman (2012), we seek to help students see how their own experiences fit with “big ideas” in “space[s] they [can] share with other writers” (p. 26). When students identify with even small parts of narratives they encounter on the DALN, they begin to complicate their understandings of audience and connection, which helps with their writing processes in pushing them to move beyond monolithic, reified conceptions of literacy and education and become more attuned to the power struggles inherent when educators privilege some forms of literacy narratives as more valid or authentic than others (Alexander, 2011; Daniell, 1999). Then, as students become more comfortable with—or at least open to the idea of—understanding literacies as mosaics, they can feel that they already possess educational assets and worry less about perceived deficits. Due to its richness in terms of diversity and complexity, the DALN is an invaluable resource in this endeavor. Perhaps nowhere else are students able to so easily access an array of written, spoken, and multimodal narratives where they are exposed to a panoramic and inclusive display of literacies.4

Methodology

In 2013, the first-year writing curriculum at our institution shifted from an unconstrained narrative assignment to a more focused literacy narrative. This change was a result of the first-semester course curriculum committee voting to shift away from an assignment it felt did not provide enough opportunity for students to grow as college learners. Additionally, many teachers voiced their concerns about not gaining a good sense of their students as writers and researchers after reading narratives that repeatedly featured superficial coverage of topics such as playing high school sports. Certainly such experiences are meaningful to students and often may in fact include important elements of literacy; however, more emphasis on the literacy aspects was needed in our assignments to ensure students examined the “so what” more than just the “what.” Of course, writing teachers know the assignment makes all the difference, so the decision was made to implement a literacy narrative assignment designed to engage students in thinking about their literacy histories and habits and to empower them to speak and write authentically about their own literacy journeys, no matter how standard or non-standard they feel those journeys may be. As part of this transformation, some teachers in the department utilized the DALN to help expand students’ understanding of the multiple literacies from which they could draw on their own experiences.

In the fall of 2015, we began to research the results of this way of using the DALN. Our research was motivated by our hypothesis that students, especially marginalized students, who engage with DALN models as mentor texts might develop an authentic and conscious awareness that, regardless of their background and/or economic status, they have rich backgrounds of lived experiences from which they can make meaning and inscribe their own literacy narratives. Further, the fact that the DALN contains narratives in different formats, including multimodal, was appealing in its possibilities for helping students think about the ways in which they connect with audiences and share information.

In this chapter, we draw on our work as teachers and as writing program administrators. As teachers, our context is the first-year composition classroom and working with first-year students; as administrators, we lead professional development initiatives for writing teachers, many of whom are first-time teachers. And while such teachers usually have a good grasp of narrative and descriptive writing, they often have little to no experience in teaching a focused literacy narrative. Further, all courses in our writing program curriculum include multimodal projects and assignments that encourage students to expand their thinking of literacies and audiences (Kress, 1997; New London Group, 2000). Often, students elect to take their written literacy narratives and remediate them into a digital mode (e.g., audio or audio-video).

The IRB protocol approved for our research project uses surveys, interviews, and case studies to examine the DALN’s impact in the work of both teachers and students. Our primary focus is experiential, and our results include data from students and teachers.5 By analyzing student experiences that begin with the introduction of the literacy narrative and their engagement over time with the different types of literacies archived in the DALN, and by analyzing the processes by which teachers become confident in their abilities to teach the literacy narrative in a way that supports students in developing multiple literacies, we show the ways in which DALN stories become mentor texts to both teachers and students. Given that our institution is located in a state infamous for multiple bottom-of-the-barrel educational achievements, a long-term outcome of our work is to reach out to writing teachers in other schools in our state to encourage their use of the DALN as mentor texts and as a repository for their students’ literacy narratives. In this chapter, we report on the preliminary phase of our research project, sharing initial results and discussing what we learned from them.

The Frameworks

In applying the DALN to our work in the classroom to engage students in literacy studies, we reference the scholarship listed in the Introduction of this chapter as well as other research in order to provide frameworks and meaning for what we see happening with students and teachers. Scholarship in the area of literacy has a rich but uneven history complicated by massive changes over the decades that include but are not limited to increased access for traditionally marginalized groups, evolving laws and norms regarding schooling, and the rapid rise of digital technologies. A commonly held belief is that literacy is always positive, that it leads to upward social mobility, greater ability for autonomy, and more opportunity for personal enrichment. Much research, though, has been devoted to deconstructing such “myths” (Graff, 1979; Bryson, 2012; Graff & Duffy, 2007), to the ideas that innate social hierarchies carry more weight than do literacies, even to the notion of literacy as violent in that it serves economic and hegemonic purposes more so than the development of the individual (Stuckey, 1991). Scholars have long disagreed on a precise definition because literacy and literacies incorporate the dynamic nature of cultural and social activities and hence resist any static definition. However, noted social historian Harvey J. Graff (1979) does acknowledge that literacy and literacy awareness can have powerful impacts on individuals no matter the prevailing social order, and we see evidence that literacy “play[s] an integral role in transformation” (Brandt, 2001, p. 190), whether that be a shifting national or global economy or simply a single individual realizing he or she might have more opportunities in life through education.

Our work focuses on this idea of opportunity and how greater exposure to the notion that literacy does not have one clear definition can benefit students as they begin to see themselves as participatory learners in control of their literate choices and practices. We draw on the definition offered by the authors of Narrative Theory and Stories that Speak to Us (Selfe & DALN Consortium, 2011) that literacy encompasses “a broad range of reading and composing activities, including writing, that take place both on and offline but are always situated in dynamic and fluid social systems” (Introduction).6 In particular, we focus on the idea that students become stronger literacy agents when they are exposed to and relate to mentor texts, especially when such mentor texts are also serving as “little” narratives—narratives that may not fit comfortably into standard notions of literacy (Alexander, 2011) but that nonetheless demonstrate how the composers of such narratives situate themselves as their own literacy agents.

The use of mentor texts, whether labeled as such or not, has deep rhetorical roots. When students in ancient Greece imitated models of exemplary speeches as part of their educations, they were enacting one of the definitions commonly accepted for mentor texts. We agree with Ralph Fletcher, writer and educator, who noted in an interview that “mentor texts are any texts that [all] can learn from… something that can lift and inform and infuse their own writing” (in Sibberson, n.d.). Students use such mentor texts to forge connections with their individual funds of knowledge (FoK), a concept which researchers Moll, Amanti, Neff, and Gonzalez (1992) explain as encompassing “the historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and well-being” (p. 133). Houghton (2010) traces FoK theory back to the work of anthropologists Vélez-Ibáñez and Greenberg (1992), who describe the formation of “strategic and cultural resources, which [they] termed funds of knowledge, that households contain” (p. 313). In this way, students can often find value in otherwise difficult (Becker, 2014) or dark (Zippin, 2009) knowledges and write about such gained knowledge (or literacies) in authentic voices, thus retaining their own agencies. Such are resources that marginalized students, and really all learners, have ready access to if they but recognize them as the powerful tools they are.

The DALN offers chances for otherwise marginalized students to see their literacies as valuable and integral parts of the many ways to be literate in America. Using the research of Newman (2012) and Bandura (1994) as lenses, we suggest that marginalized students can strengthen self-efficacy through “vicarious experiences provided by social models” (Bandura, 1994, p. 72). Because the DALN does not promote a monolithic view of literacy, students may be aided in deconstructing the false hierarchies many of them have almost always accepted. They can also see clearly the ways in which master narratives are often invoked and reified (Daniel, 1999; Alexander, 2011), leading to productive discussion about the role of literacy narratives in education writ large. DALN sample narratives thus serve as “mentor texts” and help students realize that their unique stories come from their “funds of knowledge” and should be shared rather than suppressed in fear that their experiences are “non-standard.” In this way, their experiences are situated as authentic learning that can support their academic journies.

As students use the DALN to help them break down assumptions about literacy in America, they move into constructing their own narratives. These writings are often teeming with confidence and vibrancy after students have engaged with mentor texts and expanded the ways in which they think of literacies. Verily, as writing instructors who seek to help their students produce such work, we must be open to such literacies as Lankshear and Knobel (2007) describe in their introduction to A New Literacies Sampler. In this work, the authors assert that the recognition of new literacies is not solely the result of new media, but that “new ‘ethos’ stuff” plays an important role as well (p. 7). It is no surprise that students who see others like themselves as part of a collection of literacy stories are consciously and subconsciously developing new understandings of ethos, both as individuals and as members of groups. Where once many students saw privilege given to literacies of power (particularly white, and almost certainly middle- to upper-class), the DALN allows them to see literacy as “more ‘participatory,’ ‘collaborative,’ and ‘distributed’ in nature than conventional literacies” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2007, p. 9).

It is worth noting that students’ growing understanding of literacies and broadening definitions of the term stems from use of the DALN and similar resources that ask students to critically examine literacies, not from a narrative in and of itself. Many students think open narrative assignments mean just telling a story and that they have done a good job simply if they do so. Such essays, though, often do not demonstrate critical thinking skills. Rather, they can draw in teachers with upsetting or uplifting stories that can be challenging to grade or respond to with meaningful feedback. The simple truth is a good story doesn’t necessarily mean good writing or knowledge gained. Open narratives can result in some students having an incomplete understanding of what college writing and thinking is about. This can lead to a false sense of security with Bandura’s first way of creating self-efficacy, which is through mastery experiences (1994, p. 71). A narrative assignment should not be easy; it should involve critical thinking like other college work. Yet too often students receive high scores on narrative assignments without doing much more than relating something personal. This false sense of “mastering” college writing assignments can lead to confidence-killing results on subsequent work that seems or is more complex in nature.

It is Bandura’s (1994) second way of creating self-efficacy—seeing social models—though, that has strong connections to the DALN and can help push students into meaningful writing. Bandura’s claim that “[s]eeing people similar to oneself succeed by sustained effort” often rings true for students beginning to more deeply understand their literate selves (p. 72). This can be especially so for students who have been marginalized when it comes to “traditional education.” Many marginalized students have frequently been told or infer that their knowledges are not valuable or not as valuable as those of others in traditional academia (Alexander, 2011; Ball & Lardner, 2005). Watching, hearing, and/or reading people who look and sound like them, however, can help move students from feeling like outsiders to feelings of self-empowered agents in at least two important ways: 1) establishing or further reinforcing the idea that anyone can succeed in college or in life; and 2) understanding that their “learning assets” (Zipin, 2009, p. 319) can have value beyond their own local contexts.

Teachers can help add to Bandura’s (1994) third way of creating self-efficacy, social persuasion. The more positive feedback students receive in regards to their writing, the more they are apt to feel as if they belong at the collegiate level. Ironically, this can be the case even when students are identifying their own writing, reading, and learning weaknesses. Some of the richest and deepest literacy narratives come from students who diagnose problems in their writing and learning yet become empowered through this self-diagnosis. After all, Bandura posits that those with strong senses of efficacy are not threatened by failure due to “insufficient effort or deficient knowledge” because these are areas in which they can improve (p. 71). If students with a strong sense of self-efficacy feel like they will get better through practice and focus, they are likely to do so given the right circumstances. Teachers can facilitate this growth with positive support, even if it is paired with constructive criticism. Additionally, borrowing on the “funds of knowledge” concept, students who feel that their lived experiences are valuable to furthering their education will be more likely to see their struggles as challenges and not as failures. This can also sometimes mean the difference between viewing learning as a school concept or a life concept, as teachers can help to “replace notions of deficiency by using students’ funds of knowledge and individual language to empower [students] to express themselves, to tell their stories, and to become lifelong writers and readers” (Newman, 2012, p. 25). As students progress in their awareness of the power of effective writing and composing, they are more apt to become lifelong learners in their own communities.

Preliminary Results: Student Interaction with the DALN

The literacy narrative assignment is featured early in the first-semester, first-year writing courses at our institution for more reasons than simply the widely held notion that narrative writing is a comfortable transition for students mostly fresh out of high school. Indeed, narrative, or more particularly, literacy narrative assignments invite students to consider and define their learning, or at least some aspects of their learning. In other words, such an assignment allows students to begin to understand and see themselves as academics, which they are, and the bigger picture of how literacy functions for others (Fleischer, 2000). Thus, we see the literacy narrative as a foundational piece of writing that “allow[s] students to identify and carefully cultivate an awareness of sponsorship in their literate lives” (Mapes, 2016, p. 689) and affords them a chance to examine the social complexities behind the ideas of knowledge as power. Additionally, by situating the assignment early in the semester, we, as teachers, have the opportunity to immediately evaluate how our students understand and navigate such complexities.

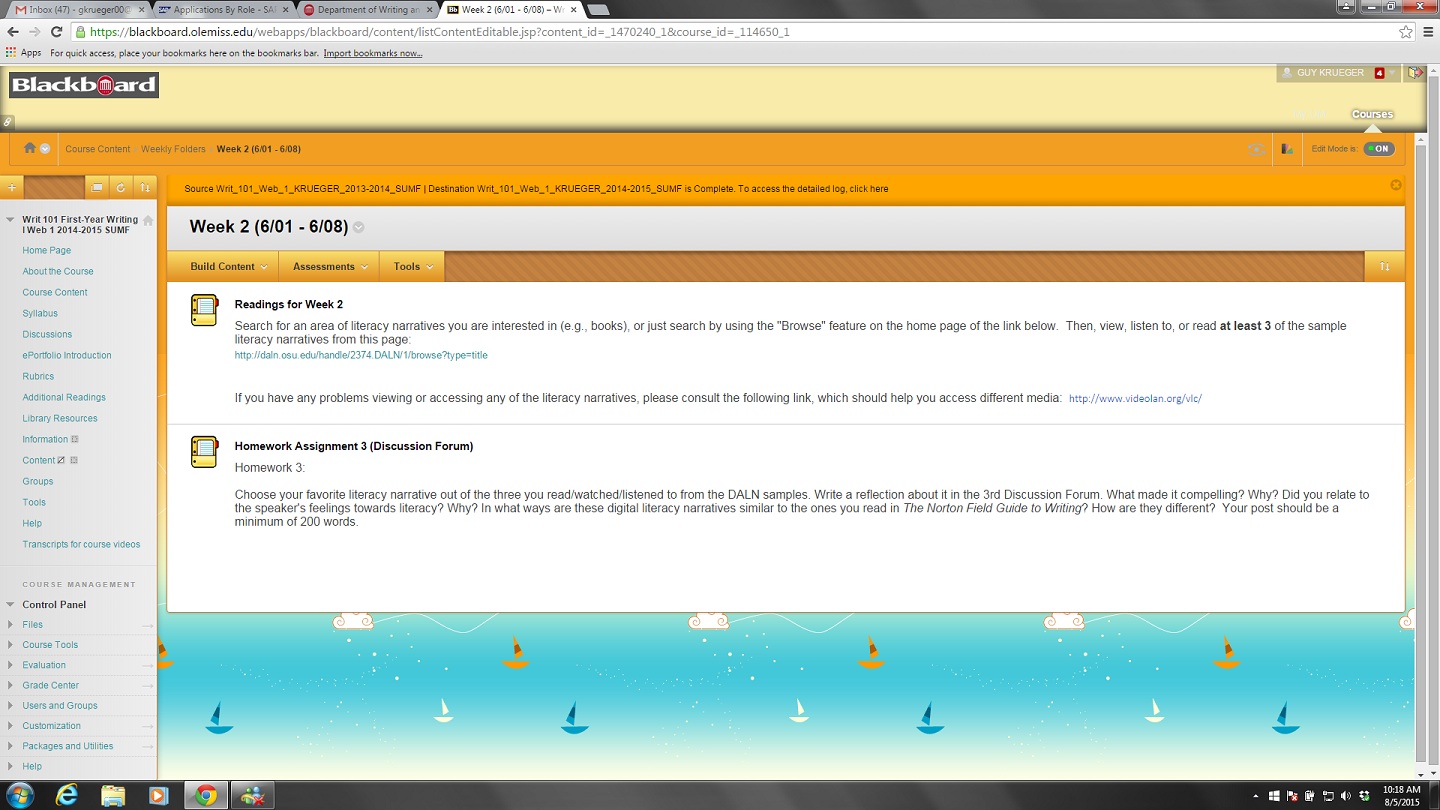

In a 2015 first-year writing course, students were asked to read, watch, and/or listen to at least three literacy narratives on the DALN website as part of the larger essay assignment (see Fig. 1). Afterwards, they had a reflective writing assignment (see Appendix A) focusing on one of the narratives that included as part of the prompt the following questions:

- What made it compelling?

- Why?

- Did you relate to the speaker’s feelings towards literacy?

- Why?

Kevin, a student from rural Louisiana who still has a large number of family members there, related closely to a narrative about how people in Switzerland have different accents in different parts of the country. For the first time, Kevin relays, he realized that people around the world shared the frustration he feels when others cannot understand him or his family members. He had always assumed, and even been told at times, that in America others spoke “correctly” and that he and his family suffered from a language deficit. Kevin reflected on how language is so often seen in terms of difference rather than similarity, but knowing that he (and, by extension, many Louisianans) was not alone in this helped him to value his own language and literacy experiences more. He notes in his reflection that he “can identify” with the author, an experience rarely part of his literate life previously because so many authors he read seemed to be speaking to others but not him. Kevin’s understanding of literacy and language is not uncommon in that prior to working with the DALN he bought into the monolithic construct of literacy and the idea that he was deficient. In many ways, Kevin needed to see and hear from others who felt outside the “norm”; he needed to encounter what Kenneth Burke (1984) termed “perspective by incongruity” to gain a richer and fuller sense of his own literacies and their value.

In these scenarios, students became literacy agents in the sense that they grew more empowered through seeing or reading others who shared similar literacy experiences. Neither of the students was high in terms of self-efficacy before the literacy narrative assignment. In fact, both students were re-taking the course after previously failing, and both wrote very deprecating thoughts about their abilities as writers in the course’s first homework assignment, which asked the class to compose a short piece about their writing selves. These initial self-diagnoses threatened to set a negative tone for the course, yet seeing social models from others who represented the students in some ways, whether through physical or cultural attributes or through shared struggle, motivated them to interrogate their own literacies with more confidence in their abilities and to perhaps escape, at least in part, the constraints imposed on their voices and agency when they worked from a deficit model.

An additional interesting aspect of these student examples is that the DALN itself legitimized the narratives they encountered. No students, not even others in the class, questioned the value or legitimacy of the narratives they encountered, this despite the fact that the homework responses were credit-based and there was no way to lose points as long as they responded with honest reactions to the questions. Either because the work was already published in some form or because the students’ understanding of literacies was growing—perhaps both—the narratives were seen as valuable literacy stories: mentor texts. The context helped students see “with conviction that these lives embody both intelligence and knowledge assets (rather than biological and cultural ‘deficits’)” (Zipin, 2009, p. 317).

Teachers, too, play an important role in establishing the value of these multiple literacies. While the DALN serves as a valuable tool in helping students see their varying literacies as meaningful, it is up to writing teachers to perpetuate that meaning as students move into different writing assignments, especially those which ask students to step outside of themselves and move beyond narrative or personal writing. It is our experience that the work students do with the DALN can help in this process, as well. Students often just need to feel as if they belong, as Denise and Kevin wrote in their reflections, to build the confidence needed to grow as writers. That confidence may sag when faced with a new and unfamiliar writing task, as students often are in first-year writing courses; however, when students interact with a resource such as the DALN early in their course, it can allow teachers to find areas to connect with students later in the course.

Our study found that some students benefitted from referencing the DALN for other assignments. For example, a third student from the same section as mentioned previously, Monique, was struggling with using sources in an argument essay that was assigned two major units after the literacy narrative. In a conference, we went back and discussed her DALN reflection on a narrative titled “Note to Self: Read Everything and Read it Again,” by Achuchigan Lattore (2015). In it, Monique wrote about how she could relate to the author’s idea that “reading means being able to explain the ideas to someone else.” She noted that in the past she had always tried to find quotes to “throw into” papers but often did not really understand the material she was quoting, at least not in the contexts of the whole works. Lattore’s narrative helped Monique see that her work wasn’t going to be as strong as it could be if she was trying to throw in source material with her thoughts. Rather, if she read—and probably read again—the materials she was interested in using, she could “understand how sources actually fit into a paper,” how “reading carefully is not just a good suggestion, it is essential if [one wants] to be in control of a paper.” Monique’s story demonstrates some of the benefits that can occur when teachers assign a literacy narrative and thus gain a stronger sense of their students as literate individuals. Better understanding strengths and weaknesses in students’ reading, writing, and learning stories can help teachers assist in ways that might not have been so clear without those unique insights.

The stories in this section are just a few examples of the types of experiences students and teachers may have when using the DALN. Though our research in many ways focuses on minority and/or marginalized students, the bigger potential value of the DALN comes in the enriched understanding of literacy, which benefits all students in any environment. Even students whose literacies and understanding of literacies have always been privileged can gain when they are exposed to the complexities of knowledge and richer understandings of how knowledge operates socially. One specific benefit of such exposure is that it ideally allows teachers to avoid the “what are you looking for” questions more and instead focus on the concepts of literacies and discourse communities.

The DALN as Mentor Texts for Teachers

While the DALN’s primary mission is to “provide a historical record of the literacy practices and values of contributors, as those practices and values change,” we have found another relevant use of the archive as a resource to support writing instruction and better understanding of writing in the disciplines (in and beyond first-year composition). Joan Mullin’s (2009) observations on “interdisciplinary literacy” resonate with us. She writes, “For methodologies to evolve, faculty and faculty development facilitators need to shift their teaching paradigms. In the case of disciplinary literacy, they need to make apparent, to themselves and their students, ways to read systems of activity and respond to [the] changing teaching and learning environments they produce” (p. 495-496). In the same article, she reminds readers of “the need to examine one’s ‘home’ language—and the complexity of voices that construct it—by entering into a dialogue with an other that would enable us to hear ourselves by standing a little outside the authoritative discourse” (p. 500). Here, the DALN facilitates disciplinary literacy when teachers use the Archive to introduce students to different types of discourse and connect the exemplars to the diverse funds of knowledge their students bring into their classrooms.

Teachers can help students use the DALN to “read” different disciplinary discourses in ways that expand understanding of other disciplines and to give students insight into the way discourses vary according to discipline. For example, artifacts in the DALN support the acquisition of disciplinary knowledge in at least two ways, the first of which is when teachers ask students to contribute a “focused” literacy narrative. An example of such would be to ask nursing students to reflect on and compose a narrative that explicitly engages with their own commitment to the nursing field and follow up by contributing the narrative to the DALN (see Appendix C for this assignment). Another way would be to search the DALN for discipline-specific keywords for an assignment that explores literacy and discourse communities within one’s major (see lesson plan in Appendix D). For example, nursing students could search for “nursing” or “nurse” and then read, listen to, or view narratives like that of Mary Ann Rollins, who had a 50-year career as a public health nurse. In her contribution to the DALN, Rollins (2013) describes what motivated her to choose public health as her field. Especially for students just beginning to study in their major, such a text could both motivate reflection while at the same time introducing students to some of the unique discourse of the field.

In another example, using the term “food science” yields a variety of results: “Nutrition in my Life”; “Learning to Write in the Social Sciences”; “Cooking as an Art”; and Austin Bahnsen’s “Becoming a Food Engineer,” (2010), in which he discusses his journey to becoming a self-described “food engineer” as he pursued a degree in Food Science and Nutrition. Using the term “engineer” returns over 100 results; among them, Jonathan Eckman (2011) reflects on the pros and cons of gaining what he describes as “engineering literacy.” Eckman traces out how his reading and writing choices changed as he progressed educationally; he writes, “My engineering literacy has changed the way in which I interact with the rest of world as well…. I now see things in terms of theories and physics instead of some other point of view.” Teachers may use these and similar entries to demonstrate how to search and view artifacts in the Archive in the classroom.

In addition to the work in our classrooms, we are also involved in sharing what we do with writing teachers from around our state via symposia we hold every fall. We point writing teachers to the DALN as a resource they may use in teaching literacy narratives in both community college and secondary school settings. Since 2009, our writing program has hosted DALN collection events, and from 2011 forward, we timed those collection events to coincide with annual Transitioning to College Writing (TCW) symposia our department hosts. At the symposia, writing teachers from around our region gather to discuss writing instruction and to learn about resources that support student writing. Attendees have both contributed to and accessed the narratives within the DALN; the artifacts in the Archive enabled them to show their students what a literacy narrative is and the various modes and mediums in which such narratives may be composed. Attendees also share what they have learned about the DALN with their colleagues.

We continue to explore ways of using the Archive’s rich resources. For example, one of us recently developed and led a workshop7 that advanced the concept of the DALN as mentor texts to introduce assignments in genres common to writing studies, sharing artifacts from the Archive that explicitly connect the genre to literacy (the PowerPoint for the workshop is in the Appendix). For example, when introducing analysis and argument, teachers could draw on Gabriella Schiraldi’s 2011 “Believe in Zero: The Rhetoric of Star Power”; beginning writers may find encouragement and inspiration from Stephen Ray’s (2012) reflections on “Conquering College Writing as a High School Senior”; and students of rhetoric, especially if new to the field, may enjoy listening to Timothy Briggs (2009) on “Discovering the Power of Rhetoric.” When introducing writing assignments, students will often pay attention to advice and reflection shared by other students and/or voices they consider authentic, and here again the DALN shines. The following table features some of the Archive’s artifacts that may be used to spark conversations about different genres.

| Genre |

Title of Entry (Linked) |

Author |

Brief Description |

| Research | “Dog Research” | Unknown | Delightful audio describing how one student used research to pitch getting a dog to her parents |

| Research | “Analysis of Literary Practices” | Murray, Briana | Briefly describes the “how” of writing a research paper |

| Creative writing, Poetry |

“Transformative Poetry for Victims of Violence” | Johnston, Emily | In a video, Johnston discusses her “evolution as a creative writer and how eventually this led to work/research on domestic violence narratives.” |

| Poetry | “The Young Poet” | Massey, Jasmine | In this brief video, Massey connects poetry, songwriting, and storytelling with learning to write and her classes at UA Little Rock. |

| Persuasive Writing | “Michigan No-Fault Automobile Insurance: Experiences with Writing to Three Different Audiences” | Prosser, Julian | Prosser’s description is spot-on: “This narrative is about writing on Michigan’s No-Fault Automobile Insurance for three different rhetorical situations.” |

The artifacts in the preceding table are brief (for the most part) and easily accessed.

What do teachers say?

As part of our IRB-approved research, we asked writing teachers how they used the DALN in their classrooms. We heard from writing teachers in high school, in community colleges, and in four-year colleges and universities. While the first stage of our research was limited in scope (the majority of respondents had attended our Transitioning to College Writing Symposium), we had responses from teachers outside of Mississippi as well. Because of our emerging interest in how the DALN may serve as mentor texts in genres beyond literacy narratives, our interview questions asked about literacy narratives and also asked if the DALN had been used in other ways.

When asked how she used the DALN, Heloise Furman, who teaches English at a private parochial school in Tennessee, replied, “I have called on the Archive as a resource, and I have shared it with other teachers here; I am using it now to plan next semester’s lessons. I want my students to do more than write about their literacy; I want them to reflect on it as well” (personal interview, December 16, 2016). When asked the same question in an email interview, Joshua Trammell, a graduate instructor at one university’s Department of Writing Studies, wrote, “I used the DALN as an introduction ‘text’ to students as I introduce them to the idea of digital literacy narrative. Students were encouraged to explore a number of video texts from the archive on their own and get familiarized with the typical structure of such narratives” (personal interview, November 28, 2016).

Most of the teachers we interviewed noted using the DALN in the ways mentioned above. When asked if they would consider using the Archive to scaffold student knowledge of other genres, all replied that they would be very interested. Furman noted how important it was for students and teachers (especially those in K-12 settings) to recognize that writing is a part of all disciplines, and she felt that the Archive’s broad range of discipline-specific contributions show how literacy is “no longer something that happens only in English classes” (personal interview, December 16, 2016). Gloria Bartholomew noted that, in addition to assigning students to explore the DALN for examples when she last taught a literacy narrative assignment, she gave them the option of contributing to the DALN as a multimodal project option (email interview, December 14, 2016). Others also relied on the DALN in teaching literacy narrative assignments; their assignments were similar to the ones we featured earlier in this chapter that are part of the Appendix section. Encouraging teachers to use the DALN as a resource in their classrooms moves the DALN beyond a mentor text for literacy narratives only; the Archive may also model reflective thinking and composing, since many DALN contributors engage in the habits of reflective thinking that we wish to foster in ourselves and in our students.

Implications

As we have described in this chapter, we find multiple opportunities for viewing the DALN as a source of mentor texts. Certainly we find a direct connection between the Archive’s artifacts and facilitating students’ development of their own agency and voice by understanding the funds of knowledge they have acquired through their lived experiences. We have seen how students make meaning from the challenges and failures they have experienced, and the DALN has been a rich and diverse repository from which our students can see how other students have engaged with experiences similar to their own. In this way, we encourage students to complicate literacy, moving past the grand narrative and the literacy myth so prevalent in many literacy narratives. Yes, it does take active searching to find complex and complicated literacy narratives, but they are there, and as Bryson (2012) notes, they are often there in the form of small narratives embedded within larger stories.

Taking steps toward complicating traditional notions of literacy may be more important than ever for our students and for us as teachers. We have, in the U.S., moved in so many ways from a workforce where high formal literacy was not a prerequisite to a decent standard of living for tens of millions of Americans to one where literacy is often currency. As Deborah Brandt (2001) posits, “Where once literate skill would merely have confirmed social advantage, it is, under current economic conditions, a growing resource in social advantage itself” (p. 169). As education and the economy change and evolve, the values we as a society place on literacy do as well. No longer may all citizens or employers see a certain degree or formal schooling as a sign of 21st-century literacy. Rather, specialized literacies that form to current social and economic trends and needs may take priority. Thus, it is so important now for students to understand that literacies are not static and that they see their experiences as having value and fitting somewhere into the tapestry of literacies. And, as we have discussed in this chapter, there are multiple ways in which the DALN can assist in this process.

While the DALN actively supports our teaching students how to navigate the complex terrain of literacy writ large, there are other ways in which the DALN serves as a source of mentor texts. In addition to showing students how other people engage with various genres, as we mentioned in the previous section, the DALN can also help students to explore language and word use. For example, teachers could direct students to learn about different literacies and the cultures such literacies represent by going to the DALN and doing a search, for example, on “the Delta” and discovering the diverse ways the word is used, ways that reach far beyond our local Mississippian interpretation of the geographic regions bordering the Mississippi River. Results in the DALN include William Chase’s delightful exploration of dialect in “Translating English - to english”; Teeny Tucker’s series of narratives “Ain’t that the Blues,” in which she explores her early learning, literacy, and songwriting; and Christine Wolfe’s explanation of the value of afternoon writing workshops for high school students in “Afterschool Writing.” All of these narratives give teachers material for engaging students in thinking deeply about the ways in which their lived experiences provide them with “ways of knowing,” while at the same time helping students to see that their interpretation of “Delta” is one of several different meanings assigned to the word/phrase. This, in turn, helps them better recognize the complexities of language and literacies.

The writing instructors we interviewed from our department also welcomed the promise of the Archive as a way of complicating notions of literacy and providing examples of different literacies that moved students to examine their own acquisition of traditional and unconventional forms of literacy. While they had used the DALN as part of their literacy narrative assignments, the notion of using the Archive to give students a beginning point for exploring new/different genres was one they had not considered. An instructor with our program is a developmental writing studies specialist: when interviewed, she immediately connected the diverse entries in the Archive to her work in encouraging students to view their lived experiences as ways of gaining literacy skills that would help them succeed academically and personally. For her students, she said, the DALN would give them models, or mentor texts, that would show them how to give voice to their challenges and fears in productive ways (Heather Woodall, personal interview, July 18, 2017).

Additionally, the DALN has personal value for teachers as well as students. We plan to explore incorporating DALN narratives in professional development activities. When we ask teachers to contribute to the DALN, they have the opportunity to reflect on how their teaching connects to their literacy acquisition and habits. In our departmental work we lead teaching circles, and there are times when we want to listen to teacher voices that are not our own, that will spark productive conversations about teaching, and that will let us be objective and less personally invested in exploring issues and challenges that arise in classrooms. There are literally thousands of artifacts in the DALN on “teaching English” and/or “teaching writing.” We recognize in the Archive a permanent resource students can access long after the first-year composition course ends.

Future Directions

As researchers, we understand the need to move beyond informal conversations and lore to a solid gathering of data (both qualitative and quantitative) that will contribute to the ongoing development of viewing and accessing the DALN as classroom: the DALN as a learning space, whether that be virtual or physical. There are opportunities to discover how Mississippi teachers are interacting with and using the DALN in their classrooms, especially based on the Transitioning to College Writing (TCW) symposia we have held since 2011.8 We have obtained approval from school superintendents who supervise teachers attending the TCW symposia to interview them about the ways in which they use the DALN in their teaching, and we are now moving into the next stage of reaching out to past attendees from K-12 settings. In doing this, we hope to gain data on if and how the Archive is used in public and private K-12 classrooms in Mississippi.

We look forward to continuing the research we have begun and bringing in more students and teachers to appreciate how the DALN might enhance the experience of reading, listening to, watching, and writing literacy narratives. Beyond the genre of literacy narrative, however, we also see the application of the DALN as a source of mentor texts beyond first-year composition that will support the agency of students as they continue to write for life.

Notes

- We discuss the frameworks, which include our understanding of literacy and our definition of mentor texts, in the Frameworks section. ↵

- See, for example, Beth Daniell’s corpus of work on literacy, especially her overview of the history of the interpretation and uses of literacy and the different theoretical approaches to literacy that she details in her 1999 article “Narratives of Literacy: Connecting Composition to Culture.” ↵

- See, for example, Rebecca Klein-Collins’ and Richard Olson’s 2014 article “Random Access: The Latino Student Experience with Prior Learning Assessment,” and Jennifer A. Sandlin and Carolyn M. Clark’s 2009 “From Opportunity to Responsibility: Political Master Narratives, Social Policy, and Success Stories in Adult Literacy Education,” both of which include closer looks at how lived experiences can count for college credit. ↵

- In this way, the DALN differs significantly from literacy sponsors, those people and/or entities that influence and foster multiple literacies among those whom they sponsor. Our emphasis here is on texts found in the DALN, which may be accessed repeatedly in either public or private settings. Our advocacy of the DALN as a repository of mentor texts supplements and expands the work of literacy sponsors without diminishing the important role such sponsors play in literacy studies. ↵

- Our IRB protocol is #16x-187; in this chapter, all names have been changed. ↵

- In particular, we appreciate their position that “[l]iteracy practices and values, as we understand them, are related in complex ways to existing cultural milieux; educational practices and values; social formations such as race, class, and gender; political and economic trends and events; family practices and experiences; technological media and material conditions—among many other factors. As the work of Brian Street (1993), James Gee (1996), Harvey Graff (1987), and Deborah Brandt (1995, 1998, 1999, 2001) reminds us, we can understand literacy as a set of practices and values only when we properly situate these activities within the context of a particular historical period, a particular cultural milieu, and a specific cluster of material conditions” (Introduction, Selfe & DALN Consortium, 2011). ↵

- The workshop was presented at the 2016 Teaching English in Two-Year College state meeting; see Appendix B for the notes for the workshop in PowerPoint format. ↵

- As visiting scholars and workshop leaders at our university, Drs. Cynthia A. Selfe and Richard “Dickie” Selfe were influential in introducing Mississippi high school and college teachers to the pedagogical value of oral histories and the DALN. ↵

References

Alexander, K. P. (2011). Successes, victims, and prodigies: “Master” and “little” cultural narratives in the literacy narrative genre. College Composition and Communication 62(4), 608- 633.

Anonymous. (2012). Dog research. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/fc797ec9-5230-46dc-85f7-9a739cee770c

Bahnsen, A. (2010). Becoming a food engineer. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/ccdd2e0a-b739-4f29-afb1-0eb726f787f3

Ball, A. F., & Lardner, T. (2005). African American literacies unleashed: Vernacular English and the composition classroom. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998).

Brandt, D. (1995). Accumulating literacy: Writing and learning to write in the twentieth century. College English, 57(6), 649-668.

Brandt, D. (1998). Sponsors of literacy. College Composition and Communication, 49(2), 165-185.

Brandt, D. (1999). Literacy learning and economic change. Harvard Educational Review, 69(4), 373-395.

Brandt, D. (2001). Literacy in American lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Briggs, T. (2009). Discovering the power of rhetoric. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/5b8772c0-4340-4eae-bcf7-b16b8ec643c0

Bryson, K. (2012). The literacy myth in the digital archive of literacy narratives. Computers and Composition, 29, 254-268.

Burke, K. (1984). Permanence and change: An anatomy of purpose (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Chase, W. (2010). Translating English - to english. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/cc5959c7-f896-4c0f-b5a5-7b15f24c3276

Daniell, B. (1999). Narratives of literacy: Connecting composition to culture. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 393-410.

Eckman, J. (2011). Engineering literacy and my new perspectives. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/3a5f6810-7913-40ec-a230-2b17f149e0c6

Fleischer, C. (2000). Literacy narratives. In E. Close, & K. D. Ramsey (Eds.), A Middle mosaic: a celebration of reading, writing, and reflective practice at the middle level (pp. 67-72). Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Gee, J. P., Hull, G. A., & Lankshear, C. (1996). The new work order: Behind the language of the new capitalism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Graff, H.J. (1979). The literacy myth: Literacy and social structure in the nineteenth-century city. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Graff, H. J. (1987). The labyrinths of literacy: Reflections on literacy past and present. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Graff, H. J. (2010). The literacy myth at 30. Journal of Social History, 43(3), 635-661.

Graff, H. J. & Duffy, J. (2007). Literacy myths. In B. Street (Ed.), Literacy, encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 41-52). New York, NY: Springer.

Houghton, H. (2010). Funds of knowledge: A conceptual critique. Studies in the Education of Adults, 42(1), 63-78.

Izzary, J. (2009). Cultural deficit model. Education.com. Retrieved from http://www.education.com/reference/article/cultural-deficit-model/

Johnston, E. (2011). Transformative poetry for victims of violence. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/0cbf0816-65e9-4212-b668-3e9c9a39c4ae

Klein-Collins, R., & Olson, R. (2014). Random access: The Latino student experience with prior learning assessment. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning.

Kress, G. (1997). Before writing: Rethinking the paths to literacy. London, UK: Routledge.

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2007). Sampling “the New” in new literacies. In C. Lankshear & M. Knobel (Eds.), A new literacies sampler (pp. 1-24). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Lattore, A. (2015). Note to self: Read everything and read it again. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/41bcf02d-f55b-46e0-adca-b1ec7f8c5c85

Lesley, M. (2008). Access and resistance to dominant forms of discourse: Critical literacy and “at risk” high school students. Literacy Research and Instruction, 47, 174-194.

Macias, A. (2012). Funds of knowledge of working-class Latino students and influences on student engagement. (Ed.D. Dissertation.) University of Redlands. Retrieved from https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/1283376349.html?FMT=ABS

Mapes, A. C. (2016). Two vowels together: On the wonderfully insufferable experiences of literacy. College Composition and Communication, 67(4), 686-692.

Massey, J. (2010). The young poet. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/7e4df42e-fd03-4cc7-93fe-61a5ab4332f8

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2): 132-141.

Mullin, J. (2009). Interdisciplinary work as professional development: Changing the culture of teaching. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 8(3), 495-508.

Murray, B. (2012). Analysis of literary practices. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/ccad5eae-5dfb-4432-81c2-62b59a5a3426

New London Group. (2000). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Learning and the design of social futures (pp. 9-37). London, UK: Routledge.

Newman, B. M. (2012) Mentor texts and funds of knowledge: Situating writing within our students’ worlds. Voices from the Middle, 20(1), 25-30.

Prosser, J. (2010). Michigan no-fault automobile insurance: Experiences with writing to three different audiences. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/fa2e82e7-1209-456b-bcd3-d34691e4402e

Ray, S. (2012). Conquering college writing as a high school senior. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/47151ae9-5038-4898-ba81-88623e951af6

Rollins, M. A. (2013). My thoughts as a teaching nurse. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/d0f02dee-4b76-4cd8-921f-8372a9349f5d.

Rose, M. (1985). The language of exclusion: Writing instruction at the university. College English, 47(4), 341-359.

Sandlin, J. A. & Clark, C. M. (2009) From opportunity to responsibility: Political master narratives, social policy, and success stories in adult literacy education. Teachers College Record, 111(4), 999-1029.

Schiraldi, G. (2011). Believe in zero: The rhetoric of star power. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/6bb9d657-eeea-49d3-8785-7d93e5bead73

Selfe, C. L. & the DALN Consortium. (2013). Narrative theory and stories that speak to us. In H. L. Ulman, S. L. DeWitt, & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Stories That Speak to Us: Exhibits from the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Sibberson, F. (n.d.) Ralph Fletcher on mentor texts: a podcast. Choice Literacy. Retrieved from https://www.choiceliteracy.com/articles-detail-view.php?id=994

Smith, A. (2010) Short bus. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/424fe97a-e0ff-473e-b112-d57b9b4a83a4

Street, B. V. (1993). Cross-cultural approaches to literacy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Street, B. & Hornberger, N. (Eds.). (2007). Literacy. Encyclopedia of language and education (vol. 2). New York, NY: Springer.

Stuckey, J. E. (1991). The violence of literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Tucker, T. (2010). Ain’t that the blues. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/644743a6-8a3d-405f-bca5-2ca0a90cb1bf

Vélez-Ibáñez, C. G. & Greenberg, J. B. (1992). Formation and transformation of funds of knowledge. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 23, 313-335.

Wolfe, C. (2011). Afterschool writing. Retrieved from http://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/b60d9a20-6d24-4395-ba5c-fa9af115527f