Chapter 6

STIRRED, NOT SHAKEN: AN ASSESSMENT REMIXOLOGY

Susan H. Delagrange, Ben McCorkle, and Catherine C. Braun

![]()

Introduction |

Evolving Rubric |

Fair Use |

Remixing Learning Outcomes |

Conclusion |

References and Appendix |

The Evolving Rubric: An Assessment Tool

Susan H. Delagrange

What is remix? Some argue that it is

APPROPRIATION,

DERIVATIVE

and

UNCREATIVE,

and as such doesn’t have a place in academic discourse. Others, primarily the heavy-handed protectors of music and film, want to argue that all use of their copyrighted material is

ILLEGAL,

a form of

THEFT.

I prefer these definitions:

Culture is remix. Knowledge is remix. Politics is remix. Everyone in the life of producing and creating engages in the practice of remix. (Lessig, 2004)

Making new stuff from old stuff in a way that has social and cultural benefits. (author unknown)

An appropriation from a source in which there is intervention and transformation of the original intent. (Packer, 2004)

In the first definition, Lawrence Lessig reminds us of what Roland Barthes (1977) pointed out in “The Death of the Author”: “We know now that a text is. . . a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. A text is a tissue of quotations drawn from innumerable centers of culture” (p. 146). In effect, there is no such thing as original expression. That said, the Copyright Law of 1976 protects the rights of authors to control “any tangible medium of expression” of their work to a much greater extent than had previously been the case, and it is only through the Fair Use clause of that document that we are given limited rights to use copyrighted material.

The second and third definitions acknowledge two specific points about Fair Use that are critical to the remix. The second definition emphasizes the claim that both copyright itself and the principle of Fair Use of copyrighted materials were designed as social, intellectual, and cultural benefits, and Randall Packer’s (2004) definition re-affirms transformative intent as a staple of Fair Use. These elements—societal benefit and transformation—are the primary focus of my remix assignments.

The Process

I use variations on a multimodal remix project in several versions of a required second-year writing class, but each class has the following characteristics:

- We work through a sequence of assignments that builds toward the multimodal remix project.

- We analyze many examples of remix prior to production—posters, fliers, ads, postcards, video, radio spots, public service announcements (PSAs), Adbusters designs—to develop a vocabulary for visual design and rhetoric. The rhetorical goals of the course are always based on advocacy (a societal benefit) of some sort, so the examples we take apart are of two kinds: media that already advocate (like PSAs and fliers from non-profit organizations), and parody remixes (e.g., produced by Adbusters) which often advocates by turning cultural commonplaces on their heads.

- The students and I collaboratively develop a rubric for analysis, feedback, and evaluation. Because we develop it together, including both the categories and the criteria, and use it throughout the assignment, it becomes a living document, evolving to suit the needs of the class and of the assignment. Involving the students in developing assessment categories and criteria helps them to develop a critical visual/verbal perspective. Used throughout the composing process, the emerging rubric provides both formative feedback for review and revision, and a summative template for final evaluation (Borton & Huot, 2007).

The sequence of assignments that culminates in the production of a multimodal artifact begins with research on the issue at hand. Because I emphasize advocacy, each student chooses a local concern about which they feel strongly and which needs to be brought to the attention of a specific audience—community, school, workplace, church, organization, etc.

At the same time the students are researching their topics, we spend time analyzing examples of existing advocacy pieces in a range of media, and it is here that the principle of the evolving rubric begins to emerge as the organic outcome of looking, talking, and thinking collaboratively about what exactly we value in such work. Bob Broad (2003) argued that rubrics are problematic, that they apply a one-size-fit-all assessment strategy that is acontextual and therefore leaves out qualitative criteria that are valued locally in favor of more quantifiable, broadly applicable standards. Broad’s proposal for writing assessment is dynamic criteria mapping (DCM), an intensive collaborative process of discovering the implicit and explicit writing behaviors valued in a particular program, and developing local criteria to assess those values.

The principle of an evolving rubric for the production and evaluation of multimedia assignments builds on Broad’s (2003) DCM concepts of local criteria and collaborative development. Class rubrics are inquiry-based, emerging piecemeal as needed from vigorous discussions of the visual, technical, aesthetic, linguistic, and metacognitive characteristics of rhetorically effective multimedia, and the criteria appropriate for assessing them. Through each stage of production, new categories are added and some fall away, and criteria for production and evaluation are refined and elaborated; the final compilation becomes the agreed-upon rubric for summative assessment and grading. (See a final rubric in the Appendix.)

The Rubric

To illustrate the characteristics of a remix and begin developing our rubric for assessment, I start with a classic example of remix from 2008 TIME Magazine (Figure 1). This image remixes the iconic photograph by Joe Rosenthal of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima with the image of a redwood, another American icon, and the text “How to Win the War on Global Warming.” Analyzing professional examples of remix like this one makes it clear to students that remix is not just YouTube fun, but a serious form of rhetorical argument.

Figure 1. A cover remix from TIME

Because too many students enter multimodal composing classes firmly convinced that the evaluation of their work will be subjectively based upon what the instructor “likes” or “doesn’t like” about the final product, our first task is to develop a common vocabulary for discussing visual remix, and then to establish categories and criteria to guide production and revision. This flexible approach makes the process of assessment more transparent to the students, and developing the rubric collaboratively creates significant student buy-in the processes of composing and evaluating their work.

It is important to keep in mind as we consider assigning remix to students that we already have a set of tools we can begin to apply to visual argument because we already know how to analyze texts rhetorically, and how to teach students to do the same. As Daniel Keller (2007) noted in “Thinking Rhetorically,” we are also learning how to incorporate professional standards for visual and audio design into rhetorically aware criteria for analyzing and assessing combinations of images, video, sound, and text. As we emphasize in our title, our assessment values and criteria are “stirred, not shaken” by adding multimodal forms to the mix. We have worked hard to figure out what we value in the writing contexts we imagine for students. Working through categories and criteria for what we value in multimediated arguments is similar to the theory and practice we use when determining how to assess writing on its own.

In the TIME cover, for example, students rather readily uncover the persuasive elements of the remix. The precarious diagonal alignment of the tree, heightened by the white space around its crown, emphasizes the similarly precarious state of the environment; further emphasis is provided by the replacement of TIME’s signature red border and masthead with the color green, and by the relationship of the text to the image, which suggests that the current war against global warming, as was the case with World War II, will be hard-fought, but winnable.

Our first set of criteria, then, is rhetorical. Based on the audience invoked by the cover (environmentally conscious readers who probably recognize the sources of the image) and the context within which the image presents its appeal (newsstands, libraries, etc.), students work together to select textual and visual elements (color, design, arrangement, repetition, narrative, process, etc.) and assign them to provisional categories: rhetorical, aesthetic, visual, technical, cultural.

Collaboration is obviously a significant component of this process, and one that we already value and assess in student composing processes. It is perhaps even more important to the process of producing and evaluating multimodal arguments. It is a commonplace that students are immersed in visual culture, but for the most part they do not cast a rhetorical or analytical eye on the media they consume. As Cathy Davidson (2011) pointed out, in an information-saturated culture, to focus is to select, and we all have blind spots. Fortunately, we each pay attention to different things, and by participating in “collaboration by difference” (Davidson, p. 20), my students make unique contributions to the analysis, interpretation, production, testing, and formative review that go on in the classroom. This idea of collaborative work as an aspect of attention is a 21st-century iteration of our previous, more narrow, acknowledgement that composing and publishing digital media requires the collaboration of individuals with both language and technical skills. Following Davidson, students collaborate first using prior knowledge and then, as their work progresses, “cross-train” by focusing on concepts and skills with which they are less familiar.

Evolution

The evolving rubric provides both structure and continuity as students research their topics, identify the belief or action for which they wish to advocate, practice remix analysis, and develop a proposal for their projects. Throughout the collecting and drafting process, we analyze examples of successful remixes and other examples of visual/textual persuasion. Early on, the goal is to identify as many categories for analysis as possible, and we generate dozens of possibilities relating to rhetorical concerns—audience, purpose, context—and to image or text—color, size, pacing, scale, alignment, repetition, proximity, contrast, framing, angle, balance, focus, line, shape, pattern, proportion, clarity, emphasis, technique—the list goes on. We keep this as a master, adding to and drawing from it as the course progresses. (See the Appendix.)

Next, we cluster related elements together and choose the first group to work on. Often, because digital media composing is new to many students, the first category is technical. Students worry that their work will not be as technically proficient as the examples we have analyzed, and this leads to a discussion of the rhetorical situation: What criteria apply to “professional” texts like advertisements or PSAs? What should we shoot for based on our purpose, context, and intended audience? After considering these rhetorical questions (although we return to them frequently as guides for design), we then elaborate on what the criteria for evaluating technical quality entail (using ratings of excellent, well done, done, needs work, and missing). For example, criteria for excellence on drafts might include clear images and readable font; excellence on a final piece might include new, class-developed criteria for cropping, spacing, alignment, and scale.

Other rubric categories evolve in a similar fashion. If applicable, we create a category for language use, with excellence requiring grammatical and syntactical perfection. When design is a category, then rhetorically appropriate criteria for alignment, contrast, emphasis, and repetition are collaboratively developed. And collaboration itself is often identified as a category, which enables the class to name (and therefore buy into) criteria for successful group work. As the rubric evolves, students become responsible for an increasing number of elements, and the criteria for each are revised and refined. The rubric becomes a heuristic device for experimenting our way toward a final outcome.

In the final few weeks, the class agrees on eight to ten categories for the summative rubric, which now includes more specific characteristics of multimedia like pacing, levels, timing, framing, and audio and video quality. All of these, of course, are defined as aspects of the persuasive situation.

Transformative Use

The rubric design described above is applicable to many multimedia artifacts. What, then, does remix ask us to do (in terms of evaluation) that is new? As Ben McCorkle notes in his discussion of copyright and Fair Use, four factors must be met to determine whether it is legal to use copyrighted material without permission:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work. (U.S. Copyright Office, 2009)

Although we consider all factors in our discussions, I focus primarily on the first. Does the remix have a new purpose and character from the original? Does it contain a new expression,a new meaning, or a new message? In other words, is the use transformative?

In the previously cited example of the TIME cover, the new message is clear, and we can see how it plays out in the metonymic identification of the flag with the redwood, which heightens the importance of restoring the tree, and the environment, to their former state, and turns that effort into a patriotic mission.

Transformative use of copyrighted material most often takes the form of commentary, critique, or parody. There are others, of course, but these are the most commonly used in student remixes. For commentary and critique, it is acceptable to remix a few lines of a poem or a few paragraphs of an article (text), as well as a few bars of a song, a few frames of a film, a few examples from a series of image, or a single image at low quality (multimedia). More extensive taking is permissible in parody. The following examples clarify these distinctions.

Figure 2. Man with Camera Remix

Commentary. The short Flash movie above (Figure 2) takes as its jumping-off point a well-known still from Dziga Vertov’s 1929 film The Man with the Movie Camera. (Note the infinite regression of the image in the viewfinder, suggesting that man/eye is equivalent to the camera.) To this image have been added a sequence of labels.

- New purpose: commentary.

- New expression: progressive labeling of parts of the image in a Flash video.

- New meaning: by assigning particular analytical terms connected with film criticism to parts of the camera and the cameraman, this short video comments on the analogy that is often drawn between the eye and the camera. In so doing, it teases out the complex cultural interface between the two, but refuses to accept the eye as a passive surface (like film) upon which the image falls.

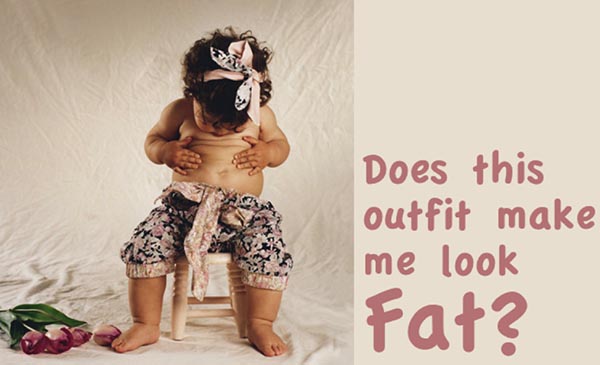

Figure 3. Remix of Geddes photo

Critique. The ubiquitous photographs of babies and children by Anne Geddes are much mimicked and much mocked. She is a franchise, with dozens of coffee-table books, baby books, and the like in print (the original image appropriated for this remix is from a 1993 calendar), and she therefore has a significant interest in protecting her copyrights. Figure 3, a student remix project, captions the image with the easily recognizable question: “Does this outfit make me look fat?”

- New purpose: Critique.

- New expression: addition of caption, published in the form of a postcard.

- New meaning: The student’s topic was anorexia, and when she began, she associated the problem primarily with teenage girls. As she researched her topic, she realized that the social and cultural pressures regarding body image were imposed (on girls in particular) at a much younger age, and she chose to call attention to this by designing this captioned postcard to be distributed to children in middle-school health classes.

How do we evaluate this remix? Technically, aesthetically, the image is lovely, but this is not the result of choices made by the student. She made, however, other rhetorically driven decisions of her own. Considering her audience and her purpose, she made decisions about her format (postcard), text message, text color, text position, proportion, arrangement on the page, scale, and other visual/verbal relationships. These were her decisions, and if she can effectively account for them, they are deserving of high marks. In addition, she was guided by the class rubric category of “Fair Use,” for which the students developed criteria to determine whether their projects adequately constructed new purpose, new expression, and new meaning. This ability to account for design decisions rhetorically is the main value of the evolving, collaborative rubric, and builds a foundation for further rhetorically effective multimedia composing.

Figure 4. "Mother Earth"

Social and Cultural Benefit. Remix, as the definitions at the beginning of this section attest, is primarily deployed to effect—through commentary, critique, or parody—some social or cultural benefit. In a course focused on advocacy, the aim of the remix assignment is to encourage belief or action that benefits the public good. For the Flash movie, “Mother Earth” (Figure 4), the class collaboratively built on a NASA image of Earth from space to craft an environmental message. With moving images, unlike single-screen remix, it becomes necessary to develop additional categories and criteria to account for temporal and audio elements. In this case, the students artfully managed the accelerating cascade of trash on the Earth’s surface, and the visual representation of thoughtless pollution is reinforced by the “fit” of the Commitments’ “Take Me to the River” to the new environmental message.

Parody. Parody, a form of critique that mocks or satirizes its subject, differs from other derivative works in that, almost by definition, it must appropriate a significant portion of the original work in order to be understood. Although I rarely assign parody, Marcel Duchamp’s well-known ready-made L.H.O.O.Q. (Figure 5) exemplifies the form. Duchamp drew a mustache and goatee on a postcard image of the Mona Lisa and titled it L.H.O.O.Q, which, when spoken in French, sounds like colloquial French for “she has a hot ass.” He has appropriated the entire image and, in a sharp critique of High Art, “defaced” it as though it were a cheap poster on a bulletin board. In terms of evaluation, parody can be difficult to assess; while the transformative nature is often clear, other Fair Use criteria (because of the slavish derivation necessary for parody to be effective, are often difficult to discern.

Figure 5.L.H.O.O.Q.

Habits of Mind

The “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” published by the Council of Writing Program Administrators (2011) proposes eight habits of mind with which students should be equipped to succeed at college-level work: curiosity, openness, engagement, creativity, persistence, responsibility, flexibility, and metacognition. I would argue that working through the development of evolving rubrics for a range of multimedia assignments fosters the growth of all these mental dispositions. In particular, collaborating over time on standards for success in remixing media for maximum social and cultural benefit strengthens curiosity, engagement, persistence, flexibility, and, perhaps most profoundly, metacognitive awareness of what students know and how they know it.

THE EVOLVING RUBRIC: THE LIST

- Identify, with students, categories appropriate for assessment.

- Choose 8 to 10 categories for the rubric.

- Using examples of successful remixes, identify the criteria for evaluation (ranging from Excellence to Missing) each category requires.

- Provide opportunities for formative reflection using all or part of the rubric heuristically—for instance, self-assessment, peer evaluation, teacher feedback.

- Customize/revise the rubric with students.

- Use rubric for final summative reflection and evaluation.

![]()