Chapter 6

STIRRED, NOT SHAKEN: AN ASSESSMENT REMIXOLOGY

Susan H. Delagrange, Ben McCorkle, and Catherine C. Braun

![]()

Introduction |

Evolving Rubric |

Fair Use |

Remixing Learning Outcomes |

Conclusion |

References and Appendix |

Remixing Learning Outcomes: Reframing Print-centric Expectations

Catherine C. Braun

Remix assignments tend to raise questions of appropriateness (from students, administrators, faculty in other disciplines) when they are used in basic and first-year writing classes, in which students often expect—and programmatic documents often promise—a more traditional introduction to composing in academic genres. Student expectations of grading, which have often been formed by exposure to traditional rubrics that emphasize issues of form and mechanics, can also be vexing. Students, particularly those in basic writing classes, often expect courses focused on grammar, punctuation, and mechanics, and they have very little understanding of rhetorical intent, audience, and context and how these rhetorical elements affect their grades. These elements might even seem quite subjective to them. As Mark Waldo and Amanda Espinosa-Aguilar (2001) pointed out, “regardless of their backgrounds, students often think that teachers grade on opinions and that the grade reflects the student’s ability to give back to the teacher what has been put forward all semester long” (p. 147).

Although Waldo and Espinosa-Aguilar (2001) were discussing traditional writing in a particular type of class, one focused on issues of diversity, this is a dilemma that teachers also face when asking students to compose digital remixes. In fact, it can be even more salient, as students often view the visual design and aesthetics integral to most remix assignments as matters of taste rather than rhetoric. The evolving rubric and Fair Use lens are two approaches to combat such preconceived notions and help students understand the rhetorical nature of design and see their composing choices in broader contexts. It is also important to consider the ways that broader institutional and programmatic definitions of writing and assessment might affect assignment design and the assessment of digital projects within individual writing classrooms.

Students often view visual design and aesthetics, which

are integral to most remix assignments, as matters of taste

rather than rhetoric.

In her institutional look at new media’s effects on writing assessment, Diane Penrod (2005) argued that new media force us to re-conceptualize not only what a text is but also the criteria by which we judge texts. Penrod pointed out that print-based assessment has been “ported” to digital composing, but that the print-based criteria favors print-based discourse, not the kind of discourse possible with new media. Therefore, institutional assessment inevitably values older forms of discourse, thereby discouraging, from a programmatic standpoint,newer forms of composing, which cannot be assessed appropriately using the old criteria. Penrod explained the implications for students and the field:

Consequently, the underlying issue that exists for the current tension that technology raises for Composition is that very different ideas are at work for discussing students’ knowledge making and knowledge producing in the writing process. We are still learning the language of how to describe and define what these knowledge making and knowledge producing processes are in the networked classroom space. (p. xx)

Like Penrod, Brian Huot (2002) argued for reconceiving writing assessment, stressing the importance of local context and rhetorical concerns of student texts and calling for “a much clearer connection between the way writing is taught and the way it is evaluated” (p. 170). Although he doesn’t specifically address digital media compositions, his assessment theory provides a model for the sort of re-conceptualizing of assessment that Penrod calls for. Instead of “porting” print-centric criteria to the assessment of new media texts, Huot encouraged us to move toward a model of assessment in which we assess “a writer’s ability to communicate within a particular context and to a specific audience who needs to read this writing as part of a clearly defined communicative event” (p. 169). In other words, rather than scoring student writing based on some de-contextualized, narrowly defined notion of “good writing,” we should have a scoring system that is highly contextualized and takes into account rhetorical elements including genre and discipline, as well as medium and/or form.

Using Penrod’s (2005) and Huot’s (2002) models, we can build a new framework for talking about and valuing disciplinary knowledge-making processes as they manifest themselves not only in print but also in new media compositions. Furthermore, we need to establish this focus on rhetoric and knowledge making in assignment design in individual writing classes. Focusing on knowledge-making processes across media can be challenging if institutional expectations are written in print-centric terms. Bob Broad (2003) explored this problem, arguing that programmatic rubrics often don’t reflect what programs (and by extension the field) really values, namely “critical and creative thinking, as well as interpretation, revision, and negotiation of texts and of the knowledge those texts are used to create” (p. 3). Such rubrics work against us, he said, because they ignore rhetorical contexts and the fact that knowledge is complex and socially constructed:

Instead of a process of inquiry and a document that would highlight for our students the complexity, ambiguity, and context-sensitivity of rhetorical evaluation, we have presented our students with a process and documentation born long ago of a very different need: to make assessment quick, simple, and agreeable. In the field of writing assessment, increasing demands for truthfulness, usefulness, and meaningfulness are now at odds with the requirements of efficiency and standardization. (p. 4)

Ultimately, Broad argued, we need to move away from error and toward rhetorical understanding in writing program documentation. The procedure he proposes is dynamic criteria mapping (DCM), a process of inquiry “by which instructors and administrators in writing programs can discover, negotiate, and publicize the rhetorical values they employ when judging students’ writing” (p. 14).

Although our institution’s writing program has not gone through Broad’s (2003) DCM process, it has articulated program values in broadly rhetorical terms. The web site of the First-Year Writing Program at Ohio State University describes the department’s writing courses and the values undergirding them:

The Writing Courses offered by the English Department are part of the three-tiered writing component of OSU’s General Education Curriculum. The Courses are aimed at different levels of writing accomplishment, and structured around different themes, but they all emphasize ways that writing is a primary element of active, creative learning in literate cultures. In their different ways, all of these courses provide students with opportunities to practice and reflect critically upon various processes of composing, forms of discourse, and methods of problem-solving, inquiry, and judgment.

Further, the writing courses offered by the English Department provide students with opportunities to engage with others’ ideas and to reflect on the institutional and cultural contexts that both constrain and enable meaningful communication with others.

This statement articulates the knowledge-making processes and rhetorical understanding students will practice and develop in general education writing classes. It is not print-centric and does not overemphasize error or “formal issues.” As such, it allows for a range of composing assignments that will fit within these parameters and does not limit composing by medium. In fact, the program encourages digital composing projects in the model curriculum it gives new instructors. The statement also avoids falling back on print-centric modes and genres, such as “expository writing” or “academic essays” (although it does not exclude them, either).

Compare the program’s articulation of goals, however, with the college’s document that spells out expected learning outcomes (ELOs) of general education writing classes in general and first-year writing in particular:

Goal:

Students build upon skills in written communication and expression, reading, critical thinking, and oral expression.

Expected Learning Outcomes:

- Students apply basic skills in expository writing.

- Students demonstrate critical thinking through written and oral expression.

- Students retrieve and use written information analytically and effectively.

First Writing Course

Expected Learning Outcomes:

- Students learn the conventions and challenges of academic discourse.

- Students can read critically and analytically. (Arts and Sciences Curriculum and Assessment Office)

A lot is lost in this translation of first-year writing. The clear primary goal is critical thinking, which is entirely appropriate, as it is a central value of the academy and one which is not necessarily print-centric. However, the way in which “critical thinking” is limited and defined in this statement is problematic for 21st-century writing classes. The old-fashioned term “expository writing” conjures an image of a particular form of writing, excluding many others and smacking of print-centricity. Likewise, the use of the phrase “conventions and challenges of academic discourse” posits academic discourse as a singular genre and masks a focus on the contexts and conditions of writing (i.e., why and when to choose a particular form of discourse over others) that is much more explicit in the English department’s statement. Revision is completely absent from the college’s description, and processes of knowledge production and inquiry are alluded to in their most mechanical sense: data retrieval and (re)use. The space for digital composition is narrow, if it exists at all.

The problem is that the college’s learning outcomes, rather than the writing program’s articulation of learning goals, are required to be on the syllabus in a general education writing class. But the larger concern is that these learning outcomes not only fail to accurately represent what the writing program says it values, but they are also articulated in print-centric terms. Consequently, they emphasize particular forms of discourse rather than the underlying discursive and rhetorical values of knowledge production in the academy. Additionally, they pose a problem for faculty integrating new forms of composing into their writing classes because of the difficulty of matching rhetorical/composing outcomes of digital media projects to the print-centric outcomes the college purportedly values.

Our learning outcomes need to change, and a

good starting point is in our syllabi and assignments.

Knowledge-making processes in the academy have up until now been almost exclusively print-centric, but that is changing. Our learning outcomes need to change as well, and a good starting point is in our syllabi and assignments. The language we use in our assignment prompts can help teach students what we value about discourse and knowledge production, not only what we value for the purpose of grading, making both more transparent. In addition, calling attention to the college’s and the program’s learning outcomes in meaningful ways and helping students reflect on them can help students make connections between composing in print and composing in other media, helping to counter claims that composing in digital media isn’t “writing.”

Such discussions can help students understand that the habits of mind we want them to develop can be encouraged through several means, in various classes, and that this is an on-going project that won’t (and shouldn’t) stop when they pass basic or first-year writing. Such discussions can lead students toward thinking about writing on a higher plane, to see writing as part of processes of inquiry and rhetorical choices situated within real communicative contexts, rather than grammar, format, and sentence-level correctness or a set of conventions divorced from context.

A key element of helping students understand their rhetorical choices is the use of what Christopher Manion and Dickie Selfe (2012) called distributed assessment—the weaving of assessment practices throughout classroom activities. Distributed assessment helps students take ownership of the assessment process and further practice the rhetorical skills that the assignment promotes. Additionally, distributed assessment practices, such as peer response and studio workshops, can help teachers make the academy’s values about discourse more transparent to students and confront the academy’s print-centric expectations about writing.

What follows is a discussion of my experience—focusing on one assignment that I often “remix,” the personal narrative—as a particular example of the ways that teaching digital composing is framed by institutional expectations about writing. (I am using the word remix slightly differently than my co-authors, referring to the process of re-composing a text in a different medium with found elements. The remixes I ask students to create are not necessarily commenting on the elements they are using for the remix—in the way that a movie trailer parody uses elements of the original as well as comments upon that original. Students do reflect on the process of remaking something and the ways in which their original alphabetic narrative is altered, however.) I discuss the ways I use this assignment in an effort to encourage students to regard composing in rhetorical terms and to move away from formal elements and the five-paragraph essay, on which they seem to be fixated. In addition, I discuss the ways I encourage students to challenge their and the university’s print-centric assumptions about writing.

The Narrative Remix Assignment Sequence

One of the problems I often encounter is that students enter my class viewing writing as a set of formal conventions. They just want to be taught the right “formula” for “college writing.” Getting them to break out of this formulaic thinking, particularly their reliance on the five-paragraph essay formula, is a challenge. One of the ways I address this is by pairing a more traditional writing assignment, the personal narrative, with a digital assignment—the narrative remix.

The personal narrative assignment asks students to write about their reading, writing, digital composing, or schooling experiences. As a variation, I may ask them to think of a non-school or non-traditional literacy they have acquired and describe how they learned it. The narrative remix assignment asks students to “remix” their personal narrative by creating a visual collage that tells the same story or makes the same argument with images only, using as few words as possible. The goals for the two assignments are parallel:

Goals of Personal Narrative Assignment

- To develop a sense of authority as a writer (i.e., feel as though you have something to communicate about a topic you are an expert in).

- To learn to use detail and specific language to describe your experience (i.e., “show, don’t tell”).

- To analyze and reflect upon your experiences with literacy skills: reading and writing in all its forms (traditional and non-traditional, “school” oriented and not).

- To analyze and reflect upon the role of instruction (both formal and informal, within and outside of school) and practice your learning of literacy skills.

- To understand the choices available to you as a composer and how to make the best choices based upon the context in which you are writing and the audience you are addressing.

- To understand how revision and peer response contribute to creating successful texts

Goals of Narrative Remix Assignment

- To compose with authority and voice in a visual realm.

- To learn to use visual detail and visual language to tell a story or make a point (show, don’t tell).

- To analyze and reflect on your experiences with literacy skills, while learning a new literacy (composing with images).

- To analyze and reflect on the process of creating the text and learning this new literacy or form of composing.

- To understand the role that medium plays in the context of composing, learn to narrow the scope of your message appropriately, choose the best visual details to present your concept to your audience, and think about audience concerns when composing.

- To understand how form and medium influence and, at times, constrain your choices regarding the visual design of your texts.

- To utilize revision and peer response to create successful texts.

To make these goals transparent for students, I state them on the assignments in media-neutral terms and, through class discussion and distributed assessment practices, tie them to the official course goals (the college’s ELOs). We also discuss the parallel nature of the two assignment goals to help students reflect critically on processes of composing and begin to make connections between different forms of composing—indeed, to help them realize that different forms of composing are valuable and that the knowledge-making processes that the academy values can be (and are) expressed in a variety of forms, depending on context, audience, and discipline.

Even when writing personal narratives—despite having read and discussed examples that do not conform to a simple formula—many students will still write their personal narrative as a kind of five-paragraph essay (although it might have more than five paragraphs) with a standard/generic introduction and conclusion. Asking them to “remix” their narratives as a visual collage is my attempt at making the familiar strange, helping them to see parallels between these composing tasks and beginning to convince them of the rhetorical nature of discourse—that it’s not about one formula for every situation, but rather making composing choices based upon a given situation and the available means (including medium and form) at their disposal. Forcing them to rethink the personal narrative genre by moving it into the visual and digital realm is a starting point for this work, as it invites them to think about the nature of composing and the underlying processes that undergird it. Likewise, a visual composing project invites students to think much more explicitly about form and the way that it affects the message. They cannot simply fall back on a formula because they think it is the “right” one. They have to think about their rhetorical intent, their audience, and their contexts in ways that they resist when writing for print.

Students’ particular challenge with this type of remix is to understand how still images can tell complex stories. Although they are familiar with storytelling forms that are primarily visual—films/videos, television shows, comic strips, etc.—they have rarely had experience composing such texts, and they have not considered the parallels between composing with images and composing with words. It is important for me to make these connections clear to students. Besides restating parallel goals on both assignments, I also require students to write a reflective statement, in which they are asked to explain their composing choices, reflect on the process of composing their visual texts, and compare it to the process of composing their alphabetic texts.

Distributed assessment practices—particularly peer response and conferencing—allow students to explore these issues while also scaffolding the assessment of their texts in such a way that they learn to evaluate their texts through the lens of the academy’s values, as Huot (2002) suggested is imperative. These moments of talking about their texts in the rhetorical terms set forth in the assignment helps students to understand what those terms mean and begin to think about their texts differently, focusing less on the formal aspects and more on the rhetorical ones. Through the process of planning, getting feedback on drafts, and revising their texts, students learn to reflect on the form of discourse they are using and how form and medium influence and, at times, constrain their choices regarding the visual design of their texts. In sum, narrative remix encourages students to think about their texts and their composing choices rhetorically, while also attending to the aesthetic and technical aspects of those texts.

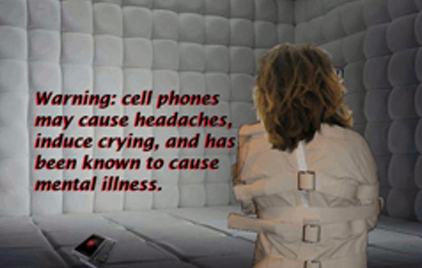

Assessing A Sample Narrative Remix

An analysis of a student-produced remix provides a particular example of how distributed assessment plays out in my writing classes. The sample remix focuses on the ways in which we are tethered to communication technologies, particularly smart phones, and how individuals tend to “go nuts” (figuratively speaking) when their phones break or are unusable. The student author of this text (to whom I will refer as “Sasha”) revised extensively, and both the rough and final drafts are shown here.

One of the distributed assessment practices used in the class is peer response. We prepare for peer response by discussing visual texts through the lenses of visual rhetoric and design. When it is time for students to respond to one another’s texts, they are well versed in discussing the target audience, purpose, argument, and appeals of visual texts, as well as describing and evaluating formal elements such as alignment, contrast, repetition, variation, perspective, balance, and color and how these visual elements support the rhetorical aims of a particular text.

Another way I use distributed assessment is by incorporating a lot of workshop/studio time into class. This gives the students time to work on their projects in class, allowing me to circulate and talk to them about what they are doing. This studio work time happens both before and after peer response. Like the peer response sessions, the studio sessions scaffold our work and model a process-oriented approach to composing. Ultimately, building a focus on rhetoric and knowledge-making processes into assignments, studio sessions, and peer response helps to distribute the assessment throughout class. Furthermore, rephrasing learning goals to remove print-culture biases helps to shift student focus from genres and forms to rhetorical awareness.

Figure 9. Rough draft of narrative remix

Peer response sessions and one-on-one discussions with me during studio workshops helped Sasha to see her text as “part of a clearly defined communicative event” (Huot, 2002, p. 169) and to create a revision plan based on rhetorical, as well as formal, concerns. The feedback Sasha received on her rough draft (Figure 9), for instance, included the following observations: that the woman was too dominant compared to the phone; that the text placement was not very effective; that the text itself was too overstated to be taken seriously yet too understated to be read as parody; and that because the phone was so small and the woman’s back was to the audience, it was difficult to tell exactly why the woman went insane (what about the phone specifically led to this result?). Additionally, from attending to the comments of her peers, Sasha realized that her actual point was not coming across very well. Her classmates understood the remix to be arguing that cell phones are “bad for you,” but the message Sasha wanted to portray was a bit more nuanced than that. During our one-on-one discussions, she explained to me that when her cell phone broke, she realized how dependent upon it she was for communicating with her friends; she articulated that her cell phone was her connection to the rest of the world, and when it broke, she felt disconnected. It was this idea that she wanted to communicate to the audience, while also suggesting that being connected to the world only through communication technologies might have some negative implications, rather than the more simplistic message that cell phones are bad for you.

Students have to think about their rhetorical intent, their

audience, and their contexts in ways that they resist when

writing for print.

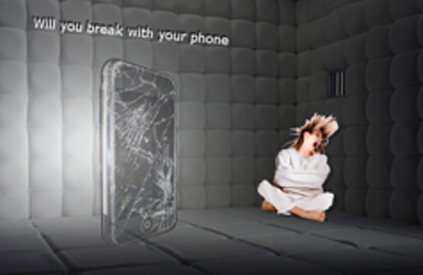

Figure 10. Revised narrative remix

Ultimately, the final draft of Sasha’s remix (Figure 10) demonstrates a strong sense of voice, purpose, and creativity; shows an awareness of audience; and uses visual design principles discussed throughout class to create not only a pleasing design but also a powerful argument that invites the audience to reflect on the role of communication technologies in their lives. Furthermore, in her reflective paper, Sasha articulated her choices using the visual design vocabularies discussed in class to explain the intended effect of each choice on her audience.

She explained that she could not find exactly the right image of a woman going crazy, so she combined three different images to get the image of the woman sitting cross-legged in the corner of the room tossing her head in anguish. In some ways, her description was very focused on the technical aspects of the composition; however, her reasoning was based on rhetorical concerns: she could not find the “right” image to portray the idea of anguish in the particular way she wanted it portrayed, so she made it herself.

Additionally, she addressed the peer feedback about the dominance of the woman and the phone; she stated that she placed the image of the phone where she did and made it slightly transparent to make it look “ghostly,” like it was larger than life and “haunting” the woman. She also revised the text not only to be a more aesthetically harmonious element in the image—by keeping it white to keep the monochromatic look that suggests gloom—but also to invite the audience to reflect on their relationships with their cell phones, an aspect that was clearly missing from her rough draft.

The more successful remixes were able to tell a story with images, but also transformed their stories into compelling arguments, as Sasha’s remix does. That rhetorical move—from narrative for narrative’s sake to interpreting/reflecting on the narrative and arguing for a greater significance to the story—was something that most students were not able to do with their written narratives, though it was part of the assignment and a point of discussion of the narratives we read as a class. However, most were able to make that leap in their narrative remixes. They were also able to use images symbolically, relate to their audience, choose the right details based upon audience concerns as well as other rhetorical and design concerns, and revise and respond to comments received during peer response sessions. Additionally, they were able to transform the scope of their original texts into something appropriate for the medium in which they were composing and reflect upon their rhetorical and design choices using the vocabularies built during class.

Remixing Print-centric Criteria:

Reframing Institutional Expectations

This assignment sequence is designed to help students recognize that every choice about every element in their texts—including formal ones that they often regard as predetermined—has a rhetorical effect on readers and is, in fact, a composing choice. In addition, the sequence helps introduce students to the notion that writing is complex and can be expressed in many forms and media, and that they need to choose the best form and medium for any given communication task based upon context, audience, discipline, and message. Assessment of the remixes is distributed throughout the term and helps students to internalize the rhetorical values and vocabulary of composing, thereby helping them learn to assess their texts through a rhetorical framework. Finally, the sequence implicitly resists the college’s expected learning outcomes and encourages reflection about the definition of writing posited by them and the limitations of such a framework for the learning/practicing of composing necessitated by the 21st-century rhetorical and media landscape.

REMIXING LEARNING OUTCOMES: THE LIST

- Build a focus on rhetoric and knowledge-making processes into assignments and assessments.

- Particularly in general education writing classes, restate learning goals in media-neutral terms, focusing on rhetorical awareness rather than on genres or forms.

- Link assessment to learning goals stated in assignments and make this linking visible for students.

- Challenge print-centric biases in institutional documents and mission/vision statements.

![]()