Following the Sox: Vernacular Journalism and Kinesiology

In the previous narrative, Charles’s use of statistics as a journalist linked with incorporating outside sources into his essays for Rhetoric 101-100. In this narrative, we can see how Charles’s history of engagement in vernacular journalism connects to writing tasks in Kinesiology 341, an advanced, writing-intensive course he enrolled in during his first year of college without having taken the prerequisites and while taking the second course in his required first-year rhetoric sequence. We begin by outlining Charles's engagements with the Chicago White Sox, his favorite professional baseball team, in his sports columns for New Expression, and then follow the intertextual linkages from his journalism into his writing for Kinesiology 341.

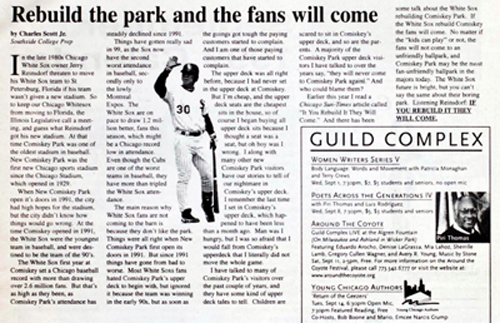

Although Charles enjoyed researching and writing stories about smoking and homework among Chicago-area high school students and the city's public transportation woes, his position as a journalist for his high school newspaper and later as the sports editor for New Expression also provided an opportunity for him to pursue his long-held dream of covering sports and writing his own sports column like the ones he regularly followed in the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times, and the Chicago Defender. While his position as editor at the magazine often kept him from writing his own stories, when he did have a chance to write a column he consistently turned toward the White Sox, the professional baseball team he had rooted for since early childhood. The White Sox provided Charles with a wealth of material for his columns. In his column titled “Rebuild the park and the fans will come,” (1999a) (Figure 6 above) published in the September 1999 edition of New Expression, for example, Charles addressed the problems with the upper deck at the White Sox’s Comiskey Park.

In this column, Charles added his own voice to those connecting the steadily declining numbers of fans attending White Sox games over the past eight years and the current state of Comiskey Park, writing,

I along with many other new Comiskey Park visitors have stories to tell of our nightmare in Comiskey’s upper deck. The last time I sat in Comiskey’s upper deck, was about a month ago. Man was I hungry, but I was so afraid that I would fall from Comiskey’s upper deck that I literally did not move the whole game. […]

Earlier this year I read a Chicago Sun-Times article called “It You Rebuild It They Will Come.” And there has been some talk about the White Sox rebuilding Comiskey Park. [...] No matter if “the kids can play” or not, the fans will not come to an unfriendly ballpark, and Comiskey Park may be the most fan-unfriendly ballpark in the majors today.

Drawing upon a recently published piece he’d read in the Sun-Times and experiences of Sox fans, including himself, Charles made a strong case for making changes to Comiskey Park, particularly to the upper deck.

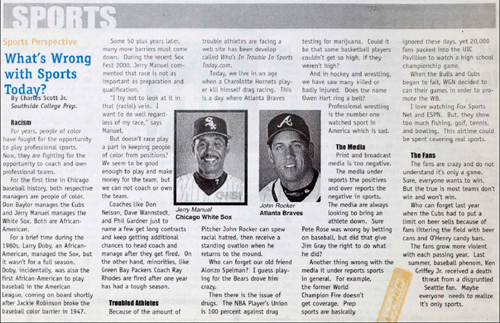

The White Sox also figured prominently in a column Charles wrote about racism in the upper echelons of professional sports. Charles's column in the April 2000 edition of New Expression, titled “What’s Wrong with Sports Today?”, (2000) (Figure 7 below) voiced a pointed critique of professional baseball’s racial inequalities, drawing specifically on Charles's knowledge of baseball history and, in particular, his extensive knowledge of Chicago’s professional baseball teams.

In the opening paragraphs of the column, Charles wrote,

For years, people of color have fought for the opportunity to play professional sports. Now, they are fighting for the opportunity to coach and own professional teams.

For the first time in Chicago baseball history, both respective managers are people of color. Don Baylor manages the Cubs and Jerry Manuel manages the White Sox. Both are African-American.

Throughout the rest of the article, Charles supported this point with portions of interviews he conducted with members of the White Sox management at the White Sox annual media event.

For Charles, these periodic columns about the White Sox were an opportunity to connect his passion for baseball with his developing interest in journalism. These textual encounters with and representations of the Sox also proved to be a valuable asset in helping him meet the demands of an advanced kinesiology course he took in the spring semester of his freshman year at the university.

Charles’s Kinesiology 341 course examined game phenomena as cultural action systems, with particular emphasis on ethnographic studies of the impact sports have on the larger society. The course, which was open to undergraduate and graduate students, required several prerequisites including the previous kinesiology course listed in the program’s course offerings. Although Charles was only a first-year student with no previous coursework in kinesiology, the instructor granted him permission to take the course. Recalling his reaction to the course after the first class meeting during one of our interviews, Charles said, “I was really intimidated when I found out that I was the only freshman, and everyone else had taken a lot of kinesiology classes.”

When Charles encountered the first of the course’s five major writing tasks, each requiring a lengthy critique of a book that addressed professional and amateur sports and their relationship to larger social and cultural contexts, his initial anxiety increased. Scholarship on basic writers has elaborated students’ struggles with the literate demands of introductory composition courses, which often require learners to read article-length pieces and write relatively brief essays or sometimes even shorter paragraph-length pieces. The lengthy and dense texts at the center of Kinesiology 341, designed to challenge the literate abilities of juniors, seniors, and graduate students, certainly required Charles, as both a reader and writer, to stretch in ways not usually assumed easy for basic writers.

Charles’s struggle with the kinds of texts he was asked to read and write was apparent in the first essay he wrote for the class. Rather than offering a critique of the core arguments of the assigned book, Bernard Suits’s (1978) The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia, Charles’s first paper consisted mainly of a chapter-by-chapter summary of the book’s content. In the two instances where Charles moved beyond summary, he did so merely by stating that he agreed with Suits’s assertions and then provided a brief example from his own experience with sports as support. We offer here an excerpt of one of those instances, taken from Charles’s discussion of Suits’s third chapter:

Suits believes that the rules of the game has a direct effect on the quality of the game. I agree with Suits. The rules of a particular game can break or make a game. Suits says if rules are defined too “loosely” the game would be boring because winning would be too easy. Suits says the less rules a game has, the more it falls apart. He also believes that without rules, we wouldn’t be able to play the games we play. Example of a game without rules is a football video game called NFL Blitz. If the real NFL were without rules, there would be no more football. Because all the players would be dead because they killed each other.

In an effort to move beyond just summarizing Suits’s point about the important role and function of rules, Charles stated that he agreed with the author. A few sentences later, he offered the NFL Blitz video game as an example of a game with few rules, and made the point that adopting this approach in the “real NFL” would cause the league to fall apart because the rules designed to protect the players would not exist.

In responding to Charles’s essay, on which he received a grade of C-, the professor focused the vast majority of her in-text and marginal comments on issues of grammar, verb tense, missing words, sentence clarity, and paragraph structure. Her other comments were aimed at encouraging Charles to read Suits’s text more carefully, pointing to specific pages for him to re-read. While the instructor did note in her brief end comment that Charles "covered all the [book's] main points,” she did not applaud the video game example he employed. Her final advice echoed her earlier comments about the mechanical aspects of Charles’s writing by stating, “[b]e very cautious of errors in sentence structure.”

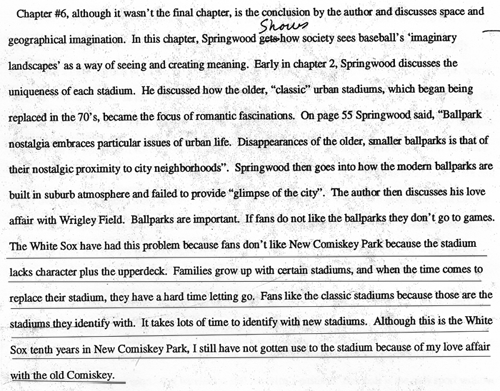

Although Charles struggled with the initial paper for Kinesiology 341, his response to the second assignment marked a clear turning point in his performance in the course. In this paper, students were asked to critique Charles Springwood’s (1996) Cooperstown to Dyersville: A Geography of Baseball Nostalgia, an ethnographic study of professional baseball. Compared with Charles’s first essay, his second one read much more like a critique than a summary, especially in terms of the ways in which Charles extended, complicated, and even challenged some of Springwood’s key points with his own insights.

In one of the essay's paragraphs, for example, Charles worked to refine Springwood's point about "ballpark nostalgia." Charles opened this paragraph (see Figure 8, below) with a quotation from Springwood about the sense of loss baseball fans felt as their beloved stadiums moved out of urban neighborhoods. He then referenced Springwood’s example of the Chicago Cubs’ Wrigley Field as one of the few parks in close proximity to the city. Having established Springwood’s point regarding fans’ nostalgia for ballparks as the focal topic of discussion, Charles then offered examples from his own home team by mentioning White Sox fans’ displeasure with “New” Comiskey Park, pointing particularly to its industrial look and enormous upper deck. He wrote:

Whereas Springwood identified the loss of connection to city neighborhoods as the source of baseball fans’ nostalgia, Charles located it in the loss of the classic styling associated with the stadiums that fans grew up with. Charles’s point was not as developed as it could be, but we read his decision to introduce the example of Comiskey Park as a way to refine Springwood’s point about the source of “ballpark nostalgia.” By using Comiskey Park in this manner, Charles was able to move away from merely summarizing Springwood’s point as he approximated the critique that his professor was expecting.

Addressing Springwood's point about the design of stadiums certainly allows Charles to draw upon the broad knowledge of Comiskey Park he had accrued through researching and writing his sports columns. But, his columns also seem to offer Charles more specific insights and discourse as well. The observations about fan's displeasure with new Comiskey Park, and with the stadium's upper deck in particular, that Charles employs to extend Springwood's point about ballparks in urban settings seem to index the content and theme of the insights he offered in his "Rebuild the park" column from September of 1999. The close similarity, both in terms of thematic framing and voice, suggest that in writing his critique, Charles drew upon insights about the stadium that were somewhat "prefabricated" in the sense that he had used them before in his New Expression story. Given that Charles had read and written about Comiskey Park in his vernacular journalism, it is easy to see how those textual encounters could inform his reading and writing for the second critique.

In the next paragraph of his essay, Charles turned his attention to a section of Springwood’s book that discussed professional baseball’s racial problems. Rather than employing his insights about the White Sox to subtly refine Springwood’s point, as he had done in the previous paragraph, this time Charles drew upon the Sox to productively contest Springwood’s position. Charles opened the paragraph (see Figure 9, below) by presenting readers with what he saw as Springwood’s central assertion that baseball’s Hall of Fame functioned to isolate racial inequalities in the sport’s past and thus erase racial issues in the present. In the next sentence, however, Charles directly contested Springwood’s position by proclaiming that “the refusal to hire minority coaches and general managers” is “a major problem [that] exists in baseball today." In doing so, Charles positioned racial inequalities as a crucial issue in need of urgent attention rather than one that has been adequately addressed and thus comfortably relegated to the sport’s history. As evidence to support his assertion, Charles pointed to the scant few African-American managers in contemporary baseball, adding that all three have winning records as a way to underscore that race, rather than coaching ability, is the central reason for the low number of Black managers:

Closing the paragraph, Charles wrote, "Yes, baseball is making progress towards equality, but problems still exist, which can only be corrected with time." In this final sentence, Charles made clear his position in respect to Springwood’s: while agreeing that baseball shows signs of moving beyond its racial problems, he also insists that such problems still exist and need to be addressed as the sport moves forward.

The details regarding the low numbers of Blacks in management positions in professional baseball that Charles employs to critique Springwood's point about baseball's racial problems seems to index the content and theme of his April 2000 "What's wrong with sports today" column. The close similarity suggests that in writing his critique, Charles drew upon insights about baseball's minority coaches and managers that he had used before in his column. Given that Charles has read and written about Black coaches and managers in his sports writing, and specifically about those coaching and managing Chicago's teams, it is easy to see how those literate encounters could inform his reading and writing for the critique of Springwood's book.

Many of the professor’s comments on Charles’s second paper, as they had on his initial essay, were directed toward sentence-level and mechanical issues. However, this time, the professor also offered a number of positive comments. In her marginal notes, for example, she praised Charles for addressing a number of Springwood’s key points. She also repeatedly applauded Charles’s effective use of examples, writing “excellent example” and “great use of examples” in the margins of his paper and indicating multiple instances where she thought Springwood would agree with Charles’s assertions. In addition, rather than focusing solely on Charles’s problems with the more mechanical aspects of his prose, the professor also encouraged Charles to address even more directly the cultural theory they were studying in class in order to provide a more focused critique and a tighter argument.

Drawing upon the knowledge he gained through his engagements with sports seemed to hold real promise for Charles as he continued to read and write for the kinesiology course. Perhaps motivated by his professor’s comments on the second essay, he again drew upon Comiskey Park in his next critique of Robert Rinehart’s (1998) Players All: Performances in Contemporary Sport. Addressing Rinehart’s point that collecting permanent “markers of experience” of major sporting events has replaced the temporary “experience” itself, Charles listed the many “markers” he’d collected and saved from attending White Sox games, including “scorecards, programs, pictures, and ticket stubs,” and elaborated on his favorite features of watching those games in person. This third essay of Charles’s earned an even higher grade than the second, and the professor’s end comment read, “[a] nice job on the main points. You tie these to interesting first-hand examples—keep up the great work. Thanks also for your excellent contribution to class discussion—It is obvious that you care about class ideas + theories.” In addition to awarding significantly higher scores on the second and third assignments, the professor had shifted the emphasis of her end comments from Charles’s sentence-level difficulties to the quality of the examples he employed in his critiques and his contributions to class discussions as well. At this point in the course, Charles’s anxiety had been replaced by a growing confidence in his ability to engage productively and successfully with the assigned texts. By the end of the semester, Charles had worked his way into an A for his overall course grade, which was based primarily on the scores for his essays.

Over the space of a semester, then, Charles moved from falling short of meeting the literate demands of the course to a level of engagement with the texts and theories that the instructor saw as exemplary. We would argue that many factors informed Charles’s improvement. In Kinesiology 341, Charles certainly encountered a number of the factors that Rogers (2010), in his overview of the findings from longitudinal studies of writing development, indicates contribute to literate development, including opportunities to write, teacher supportiveness, feedback from teachers and peers, repeat performance opportunities, and whole-class discussion, and he probably encountered these factors in some of the other courses he was enrolled in that semester as well, including Rhetoric 102-100, the second class in the university’s basic writing sequence. Importantly, Rogers’s (2010) list of factors also includes students’ pre-existing abilities and writing experiences, and we would argue that the writing-related knowledge Charles acquired through his engagement with sports journalism, and with the White Sox in particular, allowed him, a basic writer by the university’s standards, to succeed in the major writing assignments for an upper-division writing-intensive course. Charles did not intend to major in kinesiology, but passing Kinesiology 341 allowed him to continue his progress through the undergraduate curriculum and probably bolstered his confidence as a student as well.

This narrative partially traces the connection as the literate activities of Charles’s sports columns for New Expression become links in the longer chain of textual invention and production of his critique of Springwood’s ethnography. Providing an example of the interacting ecosocial systems persons inhabit, Lemke (1997) stated that “[w]e interpret a text or situation in part by connecting it to other texts and situations that our community or our individual history has made us see as relevant to the meaning of the present one” (p. 50). In the same way, Charles engaged with Springwood’s discussion partly by making connections to other texts and experiences he brought to Kinesiology via his engagement with vernacular journalism. Charles interpreted Springwood's discussion of baseball stadiums and the sport's racial issues in light of comments Charles offered in his own sports columns that addressed those topics. From this perspective, Charles's discussions of stadiums and baseball’s racial problems in his kinesiology critique included discussions of baseball, and of the White Sox in particular, in his columns for New Expression. In essence, Charles’s ability to engage with and critique Springwood’s book developed in relation to, rather than isolated from, his experience with vernacular journalism.

In linking his sports columns with his critiques for kinesiology, Charles is not randomly connecting autonomous territories of writing. Rather, he is taking advantage of the co-genetic linkages afforded by the co-evolution of practice along multiple trajectories. In this case, sports discourse, and discourse regarding professional baseball in particular, is already part of the intertextual landscape of Charles's Kinesiology 341 class. Springwood's (1996) ethnographic examination of baseball already addresses ballparks and the sport's racial dimensions. Those discussions in his book afford insights about the White Sox's stadium and the racial dynamics of the team's coaching staff and management structure, and Charles appears to take advantage of that affordance.

We attribute Charles's success on the second critique to acting with the White Sox, specifically in regard to the stadium and issues of race. But acting with these discoursal elements likely attenuated Charles's attention to many of the other themes Springwood (1996) addressed in his book, including issues of nationhood, family, gender, travel and tourism, democracy, and sexuality. This is not to say that Charles did not mention any of these topics in his critique, but he certainly did not address them with the same depth as he did the design of ball parks and the sport's racial divisions.

This narrative traces the far-flung nexus of texts, practices, and activities that Charles assembles and coordinates to accomplish his writing for kinesiology. In addition to the heterogeneous and heterochronic complexity of this nexus, we are also struck by its richly multimediated nature. Charles weaves a wealth of written texts into the lengthy chains of interpretation, invention, and production informing the second critique, including his own columns and the texts he references within them, but a number of his semiotic representations are woven into those histories as well. Charles's "Rebuild the park" column re-represents his embodied experiences attending White Sox games in both old and new Comiskey Park, including his frightful encounter sitting in new Comiskey's upper deck. His "What's wrong with sports today?" column re-represents not only Charles's experiences attending SoxFest, the White Sox media event he attended, but also the spoken conversations he had with players and coaches.

In addition to making the kinesiology course seem less like an alien world, these kinds of connections were important in other ways as well. Prior and Shipka (2003) note that in addition to weaving together literate activities, “chronotopic lamination melds together supposedly separate domains of life” (p. 205). For Charles, these laminations allowed him to weave his personal interests into his academic aspirations of majoring in journalism and pursuing a career as a journalist, thus further thickening and strengthening the entanglements between his extracurricular and curricular lives. Perhaps even more importantly, Charles’s knowledge of sports and race afforded him the opportunity to weave his school and non-school worlds together, to write himself into the university’s curriculum and extracurriculum in ways that let him create and maintain the racial identity he claimed for himself as an African American, which was no small task at a large and predominantly white college.