Survey Says: Blending Vernacular Journalism and First-Year Rhetoric

The first narrative we present focuses on how Charles appears to weave a key practice from his vernacular journalism, specifically his use of statistics from survey data, into the literate activity of his First-Year Rhetoric class. We begin by outlining Charles’s experience with using statistics from survey data as a writer for New Expression, and then follow this practice as Charles appears to incorporate it into an essay for his Rhetoric 101-100 course.

Writing stories for New Expression brought a host of new challenges to Charles’s budding abilities as a journalist. Whereas readers of his fairly small high school paper might have been satisfied with hearing how their track team had performed at a local track meet, stories for New Expression needed to appeal to and incorporate the views of students in high schools across the entire Chicago area. In order to elicit information from as many students in the Chicago area as possible, Charles began conducting surveys. He describes his experiences with creating and conducting surveys for his New Expression stories in the video clip below.

Charles quickly developed a process whereby upon identifying a topic that appealed to his readers, he generated a series of questions, typed them on a page of paper, copied it, and passed it out to other reporters/writers on the New Expression staff who would then set about polling students at their respective high schools, keeping track of quantitative data as well as recording participants’ responses. As the deadline for his story approached, Charles combined his data with that of the other reporters and tallied the results. The quantitative data these surveys generated shaped Charles’s stories in significant ways. The statistical results provided the general direction of the story (e.g., Chicago-area students say they have too much homework, smoking is a significant problem among Chicago-area high school students) and created a general framework that he could fill in with quotes from the respondents and other information.

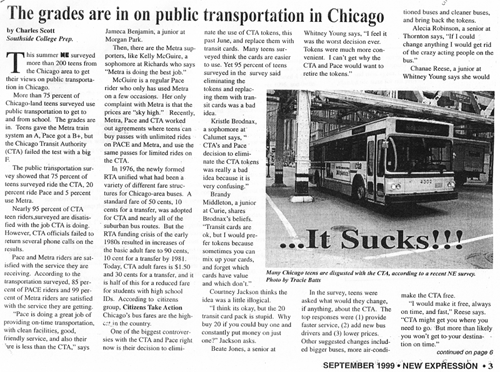

One of Charles’s earliest stories (1999b) for New Expression, a piece titled “The grades are in on public transportation in Chicago" published in the September 1999 issue, (see Figure 2 below) provides a good example of how heavily he relied on statistical data. Click on the image to view the story.

The focal point of the story, Chicago-area public high school students’ attitudes toward the city’s bus system, is established largely by the statistical data in the four opening paragraphs, which we have excerpted below:

This summer NE surveyed more than 200 teens from the Chicago area to get their views on public transportation in Chicago.

More than 75 percent of Chicago-land teens surveyed use public transportation to get to and from school. The grades are in. Teens gave the Metra train system an A, Pace got a B, but the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) failed the test with a big F.

The public transportation survey showed that 75 percent of the teens surveyed ride the CTA, 20 percent ride Pace and 5 percent use Metra.

Nearly 95 percent of CTA teen riders surveyed are dissatisfied with the job the CTA is doing. However, CTA officials failed to return several phone calls on the results.

More statistical data is interspersed throughout the rest of the story, represented in sentences such as “According to the transportation surveyed, 85 percent of PACE riders and 99 percent of Metra riders are satisfied with the service they are getting,” and “According to the survey, 80 percent of CTA riders say their bus is always late, while only 10 percent of Pace riders say their bus is always late. Also in that survey, 60 percent of those believe that Metra was the most consistent in being on time.”

As other writers at the magazine recognized the utility of conducting surveys, Charles was given the title of Survey Coordinator and charged with conducting surveys for the entire New Expression staff. As he mentioned in the video clip that opened this chapter, “It was like, like, our surveys became a very, like, powerful. [...] Like, our surveys became the basis of our stories in our newspaper when I started conducting them. So then I, like, for rest of the year, um, I conducted surveys for the whole paper.” Using survey data quickly became a crucial element of Charles’s repertoire of textual practices for putting together newspaper stories. He relied on it so heavily, in fact, that, as he iterated in the video, he found it difficult to write stories without it: “When I was the editor, because I wasn't the survey coordinator any more, I was like ‘oh my God how am I going to write a story now?’ It was, it was a challenge, writing a story without a survey."

In addition to helping him put together news stories for the magazine, this tool from Charles’s personal repertoire of voices and practices became quite visible as he worked to meet the literate demands he encountered as a student in the Rhetoric 101-100 course he took during his first semester of college.

As a first-year college student, Charles was placed in Rhetoric 101-100, the first course in a two-semester sequence designed to address the instructional needs of those students scoring in the lowest bracket of the university’s placement mechanism. Placement in Rhetoric 101-100 also required that students attend weekly one-hour tutorials with the instructor. As the instructor of the section in which Charles was enrolled, Kevin designed the course and the tutorials to immerse students in the fundamentals of source-based analytical writing. The requirements for the course consisted of a series of informal text-based writing assignments and four formal three- to five-page essays requiring students to engage with an increasing number of readings from the course textbook.

As Charles’s Rhetoric 101-100 teacher, Kevin sensed that he was struggling with both the homework assignments and the essays early in the semester. Charles's biggest difficulty seemed to be engaging with the readings in any significant way. In his first two formal essays, he appeared reluctant to include any information from the text. Although he could generate a wealth of information from personal experiences in order to address the general topic discussed in the readings, he was hesitant to engage with specific issues addressed in the readings and to incorporate information from the readings into his own essays. In cases where he did incorporate information from the readings, it was usually only after repeated reminders from Kevin or members of his peer-review group that this was a critical aspect of the assignment. Yet, even in these instances, information was incorporated in cursory ways, with Charles vaguely indexing specific information from the readings or perhaps just tacking a quote from one of the readings onto an essay’s final paragraph. We offer the following paragraph from Charles’s first essay as an example:

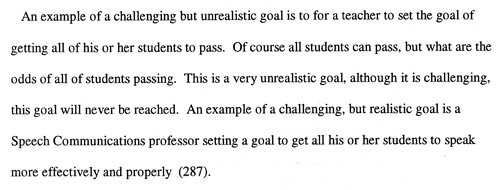

The assignment asked students to engage with a series of readings about higher education and incorporate key material into an argument about the responsibilities of students and instructors. In this excerpt, Charles extends Mike Rose’s point in “I Just Wanna be Average” that students will generally float to the mark their instructors set. Although Charles includes the number of the page where this statement by Rose is located, he does not incorporate the quotation into his essay or even signal that he is working from it.

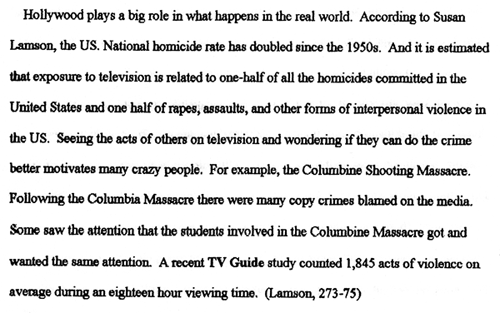

The third essay Charles submitted, however, represented a substantial departure from his reluctance to engage with the readings. Kevin had fashioned this assignment as a kind of mini-research paper dealing with the issue of sex and violence in mass media and provided the students with a list of readings from the textbook that addressed various aspects of this broad topic. Their research consisted of reading and annotating the brief essays from the book, identifying ones that addressed a specific issue, and then using information from those texts to craft an analytic argument. Charles’ essay, into which he had incorporated several passages from the readings that were rich in statistical data, represented the first text he produced that Kevin saw as successful in working with the readings. The following excerpts, which rely heavily on statistical data from two readings on the list, appeared in the first draft of Charles’ third essay and functioned as a substantial part of his argument. In the first excerpt (see Figure 4, below), Charles weaves together three pieces of statistical data from an essay by Susan Lamson (2000), causally linking the violence viewers witness on television to dramatic increases in homicides and other violent crimes over the past five decades, a link he supports with a contemporary example of the “copy cat” crimes which followed the incident at Columbine High School.

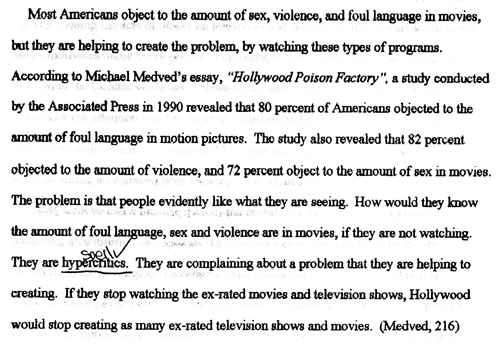

In the second excerpt (see Figure 5, below), Charles deploys statistical data from an Associated Press study cited in Michael Medved’s (2000) essay to suggest that while a substantial number of Americans surveyed object to the amount of foul language, violence, and sex in movies, Americans in general seem reluctant to turn off their televisions or turn away at the box office.

In terms of the wealth of statistical data, these excerpts from Charles’ third essay bear a striking similarity to his early news stories for New Expression. Not only does Charles employ the same attributive tag ("according to") to introduce material from outside sources that he used for his news stories, but he also uses the information from Lamson (2000) and Medved (2000) to effectively develop and extend the point he is working to make. In these two excerpts, we see Charles citing sources for statistics (with three citations in each paragraph) in the service of making key arguments. Overall, Charles cited statistics six times in this three-page draft and representations of statistics accounted for six out of nine of his citations of sources. Although Charles’ lingering difficulties with the more mechanical elements of his writing are still very much present in these excerpts, he is certainly incorporating material from sources into his essay in a more substantial manner.

The developmental trajectories articulated by Scollon (2001a) make visible the co-genetic links between seemingly disparate concepts and social practices. If we are correct in seeing that Charles was repurposing, consciously or not, a literate practice that he developed from his early experiences putting together news stories as a strategy for engaging with sources for his third Rhetoric 101-100 essay, then this narrative follows a similar link that stretches from vernacular journalism at New Expression to First-Year Rhetoric, connecting the literate activity of creating and compiling surveys, tallying results, and using the data for news stories for New Expression to the production of an analytical argument. In this sense, incorporating information from sources develops not as a single autonomous practice in one domain, but rather as a part of a historically constituted chain of specific and concrete practices that becomes for Charles the developmental pathway for the practice of quoting and citing sources. This aspect of Charles’s third essay, then, might best be understood as an aggregation of journalistic practices and those more commonly associated with First-Year Rhetoric, including the use of MLA parenthetical documentation that Charles employs in these excerpts. In blending together elements of vernacular journalism and those more commonly associated with First-Year Rhetoric, and perhaps from other literate experiences as well, Charles produced what Patricia Bizzell (1999) refers to as a “hybrid academic discourse,” a combination of “elements of traditional academic discourse with elements of other ways of using language that are more comfortable for … new academics” (p. 11).

What affords this connection? In linking journalism and First-Year Rhetoric, Charles is not tenuously bridging isolated islands of practice. Rather, he is taking advantage of pre-fabricated co-genetic links (Prior, 1998) afforded by the co-evolution of practices along multiple trajectories and which create affordances for the alignment of those trajectories. In this case, journalistic discourses, including the particular emphasis on statistical data, are already present in the context of Charles’s Rhetoric 101-100 course, already woven into the discoursal fabric of the class. Perhaps the most salient example of the presence of journalistic practice lies in the assigned textbook for the class. Many of the readings Charles encountered while working on the third essay for the course have their origins in journalistic publications. The two readings that Charles draws from in the excerpts above, for example, were both initially published in magazines. Michael Medved’s essay originally appeared in the November 1992 issue of Imprimis, and Susan Lamson’s essay was published in a 1993 issue of American Rifleman. Further, both essays employ the kind of statistical information with which Charles is familiar. Thus, the materials used for the third paper afford the use of survey data, and Charles seems to take advantage of that affordance.

Given that these excerpts from his third essay represent the first time Kevin regarded Charles as successfully engaging with the readings, we would argue that this linkage to a practice from his early years as a journalist at New Expression made a significant contribution to Charles’s success on the essay and toward his proficiency with the kinds of literate practices privileged in the academy. Charles produced a successful text, but as Wertsch (1998) would argue, it is necessary to see this success as one afforded by Charles-acting-with-mediational-means, particularly acting-with-statistics.

In terms of incorporating sources, and his writing in general, Charles still had a great deal of work at this point in the semester, as the above excerpts from his paper attest: developing a more nuanced sense of parenthetical documentation, learning to explain his ideas further and more effectively, and learning to edit his own prose (at New Expression, he had often relied on an extensive editorial process which included multiple reviews and revisions). Still, the connection Charles sensed between his vernacular journalism and the use of sources in this essay is a critical one, especially since the rest of the papers for the course (and for the later courses he would take throughout the undergraduate curriculum) tended to emphasize the use of material from outside sources for support. That Charles was able to incorporate non-statistical material from sources into his final paper for Rhetoric 101-100 (and for papers in later courses, as we will see in the following narrative) suggests that this linkage served to self-scaffold (Kamberelis, 2001) his ability to do so.