Discussion

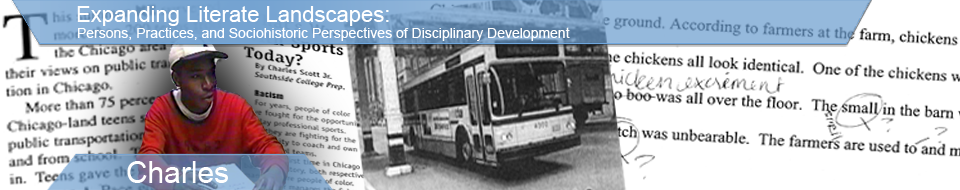

Although regarded as a basic writer based on his performance on the placement mechanism the university employed at that time, Charles brought with him a wealth of experience with vernacular journalism as he entered the university, and, as we’ve seen in these narratives, key elements from those engagements were regularly intertwined with his school writing. While these vignettes detail the linkages between vernacular journalism and school writing in three classes over multiple years, they are only three links in a more sustained and substantial historical chain of co-development over a much longer span of time. Much of this history is visible in the description of Charles’s early experiences with journalism we included earlier in this chapter. Having his entry for the essay contest published in the Chicago Defender both increased Charles's confidence in his writing for school and piqued his interest in journalism, which had already been a large part of his life as he followed his favorite sports teams. It was this interest that prompted Charles to enroll in his high school’s journalism course, and the stories he wrote and published there prompted his eleventh-grade English teacher to see him as a “good writer” for the first time. Upon graduation from high school, it was Charles’s experiences and successes in writing the news and working at New Expression that played a dominant role in his decision to major in pre-journalism as he entered the university, with the hope of one day getting accepted into the journalism program. In addition to negotiating his undergraduate coursework, Charles also wrote for the university’s paper in order to acquire the clips necessary to earn a journalism internship and later a job.

This trajectory extends beyond the third narrative as well as Charles’s vernacular journalism helped to pave his way into the workplace. When he was denied admission into the university’s journalism program at the beginning of his junior year, Charles changed his major to political science, another popular major for journalists, and promptly increased the number of stories he wrote for the school’s paper and also actively sought out other opportunities for publication. These published stories, in the form of the clips Charles submitted with numerous applications for internship positions, helped to earn him a summer internship with the Duluth News Tribune in Duluth, Minnesota, where he had 18 stories published with his byline during the summer of 2003. Thus, in the same way that Charles turned to vernacular journalism in Rhetoric 101-100 and Kinesiology 341, he also turned to vernacular opportunity spaces to keep alive his hopes of becoming a professional journalist after graduation. This strategy held real promise as his internship at the Duluth News Tribune attests. After being denied the curricular route, he had to rely on his clips and his journalistic experience; it was those that gave the internship manager at the News Tribune the confidence to select him. His experience and clips from working at the newspaper in Duluth helped him secure a second internship at a newspaper in Wausau, Wisconsin, following the end of his fourth year at the university. Pursuing his dream of working at a larger newspaper after he graduated in 2005, Charles eagerly accepted an internship with the New Jersey Star-Ledger.

What emerges from the series of connections we’ve traced throughout this chapter is that Charles’s development as an academic writer depends on not just one link between his vernacular journalism and his school writing, but rather on an entire sequence of such linkages. In other words, Charles’s abilities as an academic writer emerge from a long history of continually writing through, with, across, and against the literate activities of vernacular journalism and school, and perhaps his wealth of other literate engagements as well, from coordinating and re-coordinating a range of diverse experiences with literacy. In this sense, literate development is co-development, and the connections in this extensive co-genetic trajectory are critical in the production of a literate person. Though perhaps difficult to see and trace, the continual connecting, disconnecting, and re-connecting of diverse literate activities form the very fabric of literate life. Whereas Dias et al. (1999) argued that “we write where we are” (p. 223), we contend that writing is not just situated in various somewheres; it is an endeavor involving historically developing persons as they orient themselves on an expansive literate landscape over time. Or, perhaps it would be more to the point to say that we write who we are, and that where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going, as well as the linkages forged among them, are all threads of that story.

In response to Smit’s (2004) assertion that beyond the basic knowledge that persons do splice together seemingly diverse literate activities, there may be little more we can say about the richly literate landscapes students navigate and their growth as academic writers, this portrait of literate development across multiple literate activities suggests that we’ve only begun to articulate the way literate development is informed by multiple and diverse engagements with literacy, that we’ve only taken a few tentative steps toward fully exploring, theorizing, discussing, and understanding the various kinds of literate activities our students are engaged, their influence on each other, and the linkages forged between them. It certainly suggests that non-school literate activities are not so much extracurricular as they are co-curricular, and thus that researchers interested in understanding writing growth throughout the undergraduate years should continue to look ever more broadly at the full range of students’ literate engagements. We should look not just at the privileged literate activities done for school or work, but at the entire landscape across which students operate.