Discussion

This analysis certainly makes visible Terri’s densely textual “lifeworld,” the expansive literate landscape she inhabits that, in addition to her activities as a nurse, includes her engagement with poetry, science fiction, and memoir in addition to religious worship and documenting her family’s history. This analysis also makes visible how Terri’s seeing of patients as a nurse laminates her engagement with those literate activities, how Terri’s seeing of patients as a nurse informs her poetry, science fiction, and memoir as well as her engagement with religious and family texts.

We presented this analysis as a linear trajectory traced by Terri’s seeing of patients as a nurse being remediated across each of these literate activities in turn, but we should note that the actual nexus of connections among these engagements is much more complicated than the one we present here given how the remediations across activities were co-occuring and mutually influencing at every point. We gestured toward some of those connections, including the way Terri’s “One Nurse’s Prayer” poem indexes the linking of her poetry with her religious worship and her professional practices of care, and the way her description of standing at her best friend’s bedside in an ICU unit indexes the connection between a chapter of her memoir and her “Sonia” poem. This portrait of Terri seems to indicate other laminations, and other kinds of lamination, as well, including Terri’s engagement with her own family photos and her attention to the photos scattered around Sonia’s room. Even further linkages surfaced during our analysis of the data, including an entry in Terri’s religious devotional which describes her daughter as a patient awakening from anesthesia after a procedure.

Dias, Freedman, Medway, and Paré (1999) argued that artifacts and practices situate writers in particular cultural, social, and institutional contexts to the extent that writing for different purposes is essentially “worlds apart” (p. 222). “We write where we are,” these authors argued. “Location, it appears, is (almost) everything” (Dias et al., 1999, p. 223). Based on this portrait of Terri’s literate activities, we would argue that her acting with texts for her nursing, poetry, science fiction novel, memoir, religious activities, and documenting her family history have been continuously and intimately woven together.

Importantly, our analysis also highlights how Terri’s everyday actings with patients mediate her seeing of patients as a nurse. Ultimately, Terri’s discursive understanding of patients as a nurse is mediated as much by the inscriptions that animate her work in an intensive care unit—charts, patient notes, and incident reports, for example—as it is by the texts she acts with as she writes poetry, science fiction, and memoir and engages with religious worship and assembling albums of family photos. Some of those inscriptions, including the “One Nurse’s Prayer” poem in her desk that Terri read during her shift and the jotted passages of poems she carried in the pockets of her scrubs, are materially visible in the unit. The others, although they are present in the form of what Witte (1992) referred to as “memorial” texts (p. 265), are no less real and shape Terri’s seeing of patients as a nurse in concrete, material ways.

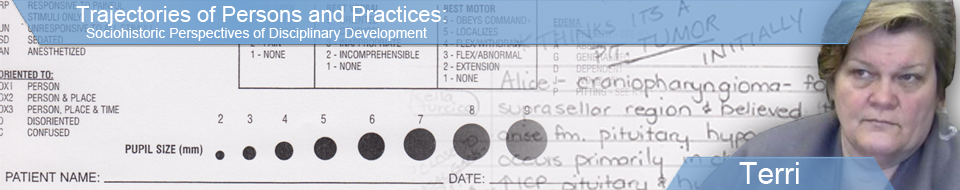

Terri’s seeing of patients as a nurse is accomplished through a densely laminated assemblage of texts and activities, some of which are local and perhaps unique to the work of professional health care, and others of which have been spun off from other engagements. To say this another way, Terri’s perspective on patients as a nurse is the result of coordinating her experiences of a wealth of professional texts, including the flowsheet and other institutional genres she identifies, with a range of other “everyday” representations. Coordinating this assemblage is what allows Terri to view “the whole patient.” As she crafts poems about Maggie and Sonia, jots notes about Alice’s character, engages with Bible verses, reflects in writing on her best friend’s passing, and reviews family photos to create a family video, with each re-seeing, Terri’s perception of patients is enriched and elaborated beyond the clinical framing offered by the flowsheet.

As a discursive practice, Terri’s seeing of patients, to echo Scollon (2001a), “has been assembled piece by piece” (p. 66) along a dialogically chained sequence of actions that stretches through all of the literate activities we have included in our analysis, and possibly others as well. From this perspective, it is easy to see why Prior and Shipka (2003) argued that literate activity is ultimately

about histories (multiple, complexly interanimating trajectories and domains of activity), about the (re)formation of persons and social worlds. … It is about representational practices, complex, multifarious chains of transformation in and across representational states and media. It is especially about the ways we not only come to inhabit made-worlds, but constantly make our world—the ways we select from, (re)structure, fiddle with, and transform the material worlds we inhabit. (pp. 3-4)

This trajectory does not just trace the development of Terri’s seeing of patients, but also Terri’s strategic and continual making and remaking of self. As Terri charts at a patient’s bedside, she is a nurse, but also a poet, science fiction novelist, memoirist, religious worshipper, and family member of cancer survivors. Wenger (1998) wrote that “we are always simultaneously dealing with specific situations, participating in the histories of certain practices, and involved in becoming certain persons” (p. 155). Weaving these literate engagements together doesn’t just allow Terri to see patients, but also assemble a literate identity, a sense of herself as a literate person in the world, that can encompass participation with this wealth of textual practices. One way Terri’s navigation of multiple literate engagements can be seen is in the “about the author” description she crafted for the religious devotional, where she wrote

[Name] is an RN who currently works in long-term care in an administrative capacity. In addition to working various positions in the long-term care setting, she has also served as a nursing consultant, case manager, critical care nurse, nursing instructor, and correctional health care provider. For entertainment she writes poetry, science fiction/fantasy, and children’s stories.

Describing herself as the author of the religious devotional, Terri felt compelled to include a wealth of literate engagements, including some not mentioned in our analysis. Clearly, these literate activities are important to Terri’s sense of herself as a literate person in the world. In this sense, Terri's trajectory is similar to other medical personnel who have integrated writing and their professions (e.g., William Carlos Williams, Lewis Thomas, Arthur Conan Doyle). Her continual engagement with multiple literate activities seems central to Terri’s long-term literate development. At present, Terri is currently working as an ICU nurse and teaching nursing at a two-year college. She is also enrolled in an MFA program working on craft essays, a collection of poems, and a fiction series.

But, Terri’s construction of a literate identity goes beyond assembling a self that can encompass participation with multiple literate engagements. Her ongoing lamination of multiple engagements also functions as a key source of identity and agency. Holland, Lachicotte, Skinner, and Cain (1998) argued that the ongoing redeployment of cultural resources from previous experiences into present situations, a process they referred to as “heuristic development,” (p. 40) is a key means by which persons author themselves as new kinds of persons. Heuristic development involves two steps: First, the redeployment of cultural resources from the person’s near and distant past for use in some present activity, and second, the appropriation of those resources as heuristics for the next moment of activity (Holland, Lachicotte, Skinner, & Cain, 1998, p. 40). “To the extent that these productions are used again and again,” Holland et al. noted, “they can become tools of agency and self-control and change” (p. 40). In repurposing resources across social worlds, then, persons are re-shaping themselves and the social identities associated with those practices. From this perspective, it is interesting to consider how Terri’s material history of acting with patients across multiple engagements allowed her to author herself as a health care professional and to challenge the way those documents readily associated with that work position caregivers and patients.

The lamination of these multiple seeings of patients across multiple, seemingly disconnected engagements allowed Terri to author herself as a health care professional who could see “the whole patient” and thus be a more effective advocate for their care. It is clear from Terri’s discussion of the origins of her “One Nurse’s Prayer” poem that she encountered very early in her LPN schooling a professor who she admired and respected and who impressed upon her the need to be a “patient advocate,” who imparted an ethic of patient care that addressed the whole patient. As we’ve seen, that ethic was maintained, sustained, supported, reinforced, refined, enriched, extended, amplified, and further developed for more than three decades by a densely laminated assemblage of discursive practices and literate activities, including her later poems but also the science fiction novel she planned and researched, the memoir she was working on, her religious devotional, and the video she assembled for her family.

Discussing her “see me” poems during one of our interviews, Terri stated, “I think writing about patients in the way that I do allows me to respond to patients' and families’ needs with a patience and compassion I would not have possessed had I not stopped to consider the issues I cover in my writing.” Terri’s comment is focused on the poetry she wrote about patients, but we think that her statement encompasses her other literate activities as well. Each of these textual engagements, we argue, served as an opportunity for Terri to examine how patients were regarded and could be regarded in ways that more prominently foregrounded their humanity and dignity.

In addition to helping her craft a self that could care for her patients and their families, the lamination of these multiple seeings of patients across multiple, seemingly disconnected engagements also provided Terri with a means of authoring herself as a health care professional who could navigate the emotional demands of palliative and emergency care and productively resist the way the texts she routinely encountered on the job positioned her. Talking about her “see me” poems, Terri stated that, “If you don’t ever think about those things, how can you address them? I think it was important for me to deal with those issues in some fashion, and that was the fashion that worked for me. I don’t think I could have survived as long as I did without that, because it was too dehumanizing. This [pointing to the flowsheet] is too dehumanizing.” Elaborating, she stated, “I would not have made it as long as I did without being able to get rid of that [the depersonalization] in some fashion, to express it, to articulate it, to say, even if nobody heard me anywhere else. I don’t think I would have made it as long as I have.” Again, Terri’s comments here are focused on the poetry she wrote about patients, but we think that her statement encompasses her other literate activities as well. Her comments about her science fiction and her memoir especially speak to those activities helping her to work through the emotional demands of her work as a nurse.

This perspective productively complicates Paré’s (2001) argument that the “transformation of the self into a “professional … is a transformation realized through participation in workplace genres” (p. 68). Paré argued that “this erasure of the self—or more accurate, perhaps—transformation of the self into a ‘professional’ locates the learner anonymously within the institution’s naturalized ideology. It is a transformation realized through participation in workplace genres” (p. 68). Where does Terri’s “transformation” into an identity as a nurse “locate” her? Paré seems to suggest that professionals act with workplace genres as a way of setting aside their lifeworld, a way of setting aside other identities and positionings in order to take up more wholly those invited by workplace documents, a means of occupying some more central positioning in the professional community. This portrait of Terri’s seeing of patients suggests something very different.

One key question that arises as these connections among seemingly separate literate activities are brought into focus is “Who is doing the linking?” Our analysis focuses intently on Terri’s coming to see patients throughout her life span, but we need also to emphasize that its development in Terri’s history is intimately connected to its sociogenesis, its propagation through society. Such a move is in keeping with Scollon’s (2001a) observation that the cultural resources persons act with are always linked to two histories, “a history in the world [and] a history for each person who has appropriated it” (p. 120). It is important to note that it is not Terri’s actions by themselves that forged these linkages. Rather, Terri is inventively taking advantage of what Prior and Shipka (2003) described as “co-genetic” linkages created as the collective propagates representations of health care throughout a society’s multiple activities. Consider, for example, Terri’s account of what got her started writing poetry about the patients under her care:

When I was an LPN, a new LPN, we had, in one of the places I worked, there was a poem stuck up in the, um, linen room. It was a Xeroxed copy stuck up with a thumbtack in a linen room. It was where the aides went when they had to get linens. It wasn’t where the nurses usually went often, but I worked night shift so sometimes I needed to get in there. And, I don’t remember the title of it, but the message was “see me,” and it was about "this is what you [the nurses and doctors at the hospital] see now," this old and broken down body, you know, and it was beautifully written, and I can do no justice to it at this point. But it was about the difference between what you see now and who I was, I had this family, you know, I did these things, I had a child I loved. So, that was there, but it was years before I wrote anything even close to that. It stayed in my head, though, I remembered it.

Here, Terri describes encountering a poem in the unit’s linen room written by someone else that takes up the theme of seeing patients. It is this poem, Terri indicates, that prompts her, although years later, to start writing similar poems. Over the course of our interviews, Terri recalled additional encounters with other people's poems related to health care. In one instance, Terri talked about attending a poetry conference and hearing poet Jeanne Walker Murray read a poem titled “The Nurses,” which is about nurses working on a cancer ward, from her recently published collection of poems and purchasing a copy of the collection. Terri stated, “It is a beautiful poem. And I was so moved by it. So when I came back to work, I brought it and said ‘Look at this.’”