Discussion

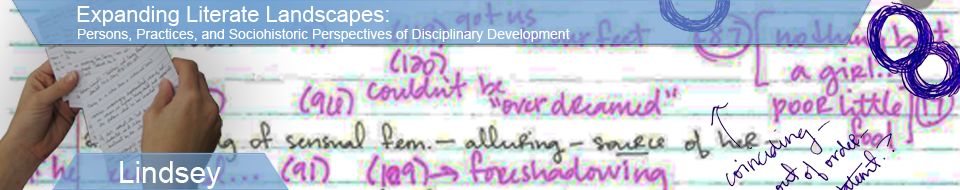

Configuring Lindsey’s engagement with this discursive practice in terms of the Composition Approaches for Teachers course, it could have appeared that her history of development with this practice began early in the semester as she encountered the “scissors, paper, tape” revision exercise in the course textbook and then continued throughout the semester as she invented and arranged “Cotton.” But, as we’ve seen, Lindsey’s participation with this practice extends far beyond creative writing. In inventing and arranging the lyric essay, Lindsey is acting with a discursive practice that she has re-made and semiotically remediated across a lengthy historical trajectory stretching across a number of engagements. In the same way that Charles’s performance in Introductory Journalism and Kate’s performances for her courses were the product of their histories across multiple textual engagements, when we see Lindsey’s physical manipulation of the various elements for the “Cotton” essay, we are not just seeing the result of her history of engagement with that discursive practice for creative writing; rather, we are seeing the result of her repurposings and semiotic remediations across doing graphic design, arranging literary analyses, and crafting creative writing. We see, in other words, this practice as it has been elaborated and aggregated for use across these three nexus of practice.

Lindsey’s historical sequence of repurposings of discursive practices from her engagement with art and design did not end with composing the lyric essay. The very last course Lindsey took to complete the requirements for her master's in education in the fall of 2009 was a web design course offered through the university’s communication department. Talking about the web site she put together for that course during our interviews that semester, Lindsey frequently mentioned the discursive practices she used. She mentioned, for example, how she had employed some strategies for determining perspective to organize information on the opening page of her site:

So, in art and photography, in art, your point of focus should be here, here, or here, and then everything goes out from that point. The other thing is, if you’re going to center something on a page, this is all graphic design, if you’re going to center something on a page, you always drop it lower than the center, because otherwise it looks like it's floating. So when I did my website, my page has my buttons here, and this is the picture.

Lindsey also anticipated how her disposition toward physically manipulating texts might inform her future engagements. During her final semester of her MEd program, Lindsey learned that she’d been selected to teach at a junior high school for the following academic year, a school that provided all of its students with laptop computers and encouraged teachers to use them as much as possible. Lindsey stated during one of our interviews that upon receiving the news, one of her first thoughts was that she would “have to learn how to teach all over again because I like to do things by hand” and often incorporated that into her teaching.

These kinds of repurposings across engagements are not just essential to the development of practice, but to the development of Lindsey’s identity as well. Scollon (2001a) wrote that “any action which is taken reproduces, and claims, imputes, contests, and recontextualizes the identities of prior social actions as well as negotiates new positions” (p. 7). From this perspective, it is interesting to consider how Lindsey’s repeated reuse of a practice for art and design allowed her to maintain a sense of herself as an artist as she participated in other disciplinary worlds. Talking about her decision to stop majoring in graphic design, something she had wanted to focus on since she was quite young, at the end of only her first year of college, Lindsey conveyed that it was a hard decision, but she didn’t think that she was talented enough as a graphic designer to eventually get a job doing that after graduation. Her decision to settle on English as a major was prompted by her sense that it would prepare her for a number of careers, but also because reusing the discursive practices from graphic design to assemble her papers for literature classes allowed her a way to still be an artist. As Lindsey stated, through assembling papers for her initial literature courses, “I found that I could satisfy my need to draw by preparing for papers. It felt like the same kind of rendering process.” Her reuse of that practice for creative writing, and the many other elements from her experiences with art, allowed her to draw her participation as an artist into her participation as a creative writer, thereby authoring a sense of herself as a creative writer that includes her sense of herself as an artist.

It is interesting to consider the even longer-term implications of Lindsey’s efforts to maintain a sense of herself as a designer across these engagements. As a language arts teacher at the new junior high school, Lindsey developed a curriculum that immersed her students in the visual arts as a way to engage with the literature they read and studied and the various other kinds of reading and writing they did. Her classroom activities regularly involved students in creating visuals and artifacts by hand. After two years of teaching junior high, Lindsey and her daughter relocated to a larger city in the southeast where Lindsey and some others started a production company specializing in web development and social media marketing. We can only imagine how Lindsey’s physical manipulation has developed as a result of her engagements with web development and marketing, and for what future activities those uses are preparing it for. We can also only imagine how Lindsey’s identities as an artist, literary critic, creative writer, and teacher are shaping her work and life at present.