Introduction

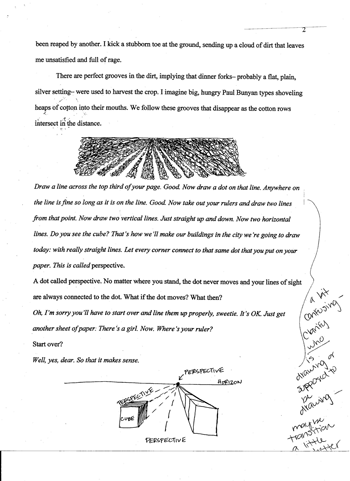

In crafting “Cotton,” the piece of creative non-fiction she was working on for her graduate course in education focused on the teaching of creative writing, Lindsey Rachels (a pseudonym) spent several months continually organizing and re-organizing on various flat surfaces around her home pieces of paper containing textual descriptions and images representing some of the most poignant moments of her life—sometimes shuffling them around on her desk, dining room table, and countertops, and at other times taping them up on the walls and windows. The page from one of Lindsey’s later drafts of “Cotton” shown to the right (Figure 1) is the product of her constant arranging and re-arranging of the prose and images she worked with. This “physical manipulation,” as she repeatedly referred to this practice during our interviews, was her way of coming to understand how these written and visual representations of a number of disparate events—her childhood visits to her grandparents, scenes of playing in the cotton fields that bordered her grandparents’ home, her pregnancy, memories of her grandfather’s passing—might be arranged to create a coherent lyric essay. According to Lindsey, the act of organizing and re-organizing these sections of text played a crucial role in helping her create a unified essay. “Without it,” Lindsey stated, “I couldn’t see how everything fit together, which piece goes where and how they all relate.”

Lindsey’s mention of physical manipulation allowing her to “see” how the various written descriptions and images might be organized points toward its function as what Goodwin (1994) referred to as a “discursive practice” (p. 606). According to Goodwin, discursive practices are the “historically constituted architectures of perception” (p. 606), the processes and procedures, through which a profession’s relevant objects of knowledge are shaped, produced, and understood. Describing the role of this shaping process in the production of knowledge, Goodwin wrote,

[d]iscursive practices are used by members of a profession to shape events in the domain subject to their professional scrutiny. The shaping process creates the objects of knowledge that become the insignia of a profession’s craft: the theories, artifacts, and bodies of expertise that distinguish it from other professions. (p. 606)

In acting with the discursive practices privileged by a particular community, participants develop what Goodwin called “professional vision,” “the socially organized ways of seeing and understanding … that are answerable to the distinctive interests of a particular social group” (p. 606).

The focus of this chapter is the development of this discursive practice in Lindsey’s history, how she came to appropriate it, especially given that this was Lindsey’s first creative writing class.

Lindsey’s practice of physical manipulation locates her in the disciplinary world of creative writing. And yet, much like Charles and Kate, it is also part of an extensive history that extends beyond the assumed borders of creative writing. However, where Charles and Kate’s disciplinary engagements were mediated by their vernacular literacies, Lindsey’s engagement with creative writing is mediated by a history traced through other disciplinary worlds.

While dominant perspectives would locate the development of this practice within Lindsey’s engagement with creative writing, we argue that attention to her participation with creative writing alone is insufficient to understand its developmental path. We argue that the discursive practice Lindsey employs to arrange “Cotton” had developed along a lengthy historical trajectory of use across multiple activities, including graphic design and literary criticism. Much like Scollon (2001a) traced the varied contexts tied together in the ontogenesis of the practice of handing, our analysis of Lindsey's physical manipulation argues ultimately for a more dispersed, complexly mediated, and heterogeneously situated understanding of the development of discursive practice.