11. Maps, Stamps and Plans

Using Visual, Interactive Course Documents to Promote Student Autonomy and Engagement

Vignette

It is the last half hour of my class on visual rhetoric and contemporary comics. Up to this point, the day has focused on Scott McCloud’s taxonomies of ways to represent a comics character, his “big triangle” that charts the granular semantic waypoints between iconographic, realistic, and abstract representation in comics (1994, pp. 52–53).1 The final half hour is reserved for students to present projects they've been working on independently. I legitimately don't know what's coming.

A student I will call Julie presents a collage on the big screen. Her task was to take two comics from different artists and compare how they use medium and genre conventions to reach their audience (or maybe their fanbase). She had to create a complex visual collage that communicates her analytical comparison nonverbally. She’s chosen the tragic and touching Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles (Russell et al., 2018) and the bizarrely experimental sci-fi fantasy Proxima Centauri (2018) written and drawn by Farele Dalrymple.

Julie gives a brief introduction to the pieces for the class, which they need because only a few other students picked these same comics to read this quarter. We all take a minute or two to examine the collage before we have a Q&A, after which Julie returns to her seat. We all sit quietly for a moment while everyone, including Julie, opens the class “rule book,” finds the “artist collage” project, and uses the rubric to judge whether the collage is complete and ready to earn points. I collect each students’ ballot and add my own to the pile.

I also collect Julie’s game board syllabus, which is very well used, covered with scribbles and white-out. She has already gathered a bunch of stamps for finished projects, and her point meter is climbing fast. Since the class has no deadlines, she’s made her own, writing them in by the assignments she’s chosen to do, writing the days she intends to finish them in pen. Astoundingly, she sticks to these deadlines without fail. I suspect she’ll keep it up.

After I tally up the class’s evaluation of her collage, I stamp two more points onto her game board. I will return it to her next class, when some other students will show what they’ve been working on.

Introduction

One important way WPAs influence the ethos and teaching practice of their programs is through the introduction of new curricular documents such as model syllabi and rubrics. In addition to providing guidance for instructors teaching in the program, these documents enable new structures for student-teacher interaction that can make a significant difference for what is possible in the writing class. Since I am a WPA whose first-year writing program is taught entirely by two-year master’s students, I have often looked to these documents as a place to intervene in the way students and instructors interact in the classroom. I know that every time I introduce a new rubric, contract, or syllabus model, it will have downstream influences on these developing teachers and the students in their individual classes.

The grading contract movement has caused WPAs to consider the power of innovative curricular documents in new and exciting ways. Grading contracts allow course designers to change the incentive system students and teachers work under (Inoue, 2019). In many models, rather than judging student work for expert performance according to a particular standard, the contract evaluates students on their commitment to learning as represented through projects completed, class participation, and other metrics deemed to be fair and equitable (Danielewicz and Elbow, 2009). Asao Inoue has argued that curricular models such as grading contracts—especially contracts that assess students at every level only on student labor—allow writing classes to move away from privileging dominant, white language traditions that are baked into all composition classrooms (Inoue, 2015, 2019a, 2019b). As WPAs from around the country take up Inoue’s approach and respond to the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC), we can witness a growing movement to let curricular document design be an agent for cultural change.

We see another aspect of the importance of curricular document design as we consider matters of accessibility and modality. Thanks to the rising influence of disability studies within WPA, we also see increased attention to the ways curricular document design can influence cultures of disability and access at the classroom and programmatic levels. When we mandate a particular accessibility statement for our program, for instance, we set the tone for how instructors will react to students’ requests for accommodations, or whether a student will feel invited to make those requests in the first place (Wood & Madden, 2014). But Anne-Marie Womack points out, beyond matters of policy, our curricular documents often manifest a philosophy of disability exclusion through their very design (503). How different would our programs’ required syllabi look, for instance, if they took into account the reading needs of students with learning disabilities, dyslexia, or attention disabilities (Womack 508–512)? Accessibility questions such as these point to yet another avenue that WPAs are taking to use curricular document design to affect the cultural dynamics of their programs.

Over the last decade, the composition instructors and course designers have begun exploring what is possible when we incorporate the principles of game design into our classrooms and curricular materials. As one example, the annual CUNY Games Conference brings together professionals from history, literature, biology, writing studies, education, and other fields to test out game-based course materials and learn about new approaches to infuse our classes with playful learning. It is in these venues that we see what makes Game-Based Learning (GBL) particularly valuable for curriculum design. Games like board games and card games are inherently multimodal and usually highly visually engaging; at the same time, their use is governed by meticulously fine-tuned rules and game mechanics. Games rely on clear, engaging visual design to communicate those rules and mechanics, to display what is possible and what isn’t within the ecology of play. We course designers often use prose syllabi and course descriptions to achieve the same ends, written in prose like a missive for students to receive.

As GBL scholarship has begun to make clear, game-based approaches, which inherently tap into nonverbal, interactive modes of communication, push us to use visual rhetoric and material design to reconceive organized social spaces and programs. This is because GBL operates through a rhetoric of choice—where image, word, and materiality all combine to communicate to the student-player what moves are available to take, what may happen if they are taken, and what is to be gained or lost in the process. This is not so different from when we design any course documents. We might already join Graban and Ryan in their assertion that curriculum development should be seen as “a form of knowledge production and generic reform” (2005, p. 90), whereby writing a new syllabus or course guide can and should accompany real ideological changes within a program. But with GBL, we engage unique forms, visual communication, and interactivity in our course designs, pushing the possibilities of curriculum design, and thus our pedagogical ideologies, in important ways.

My aim in this chapter is to describe an approach to game-based curriculum design that uses a central visual-interactive document to organize the day-to-day mechanics of an entire writing class. The system I developed uses a “playable syllabus” in the form of a personal game board each student uses to track their progress throughout the course and to make individual decisions about which assignments to do and in what order. The game-based curriculum provides important structure and order for a course I intentionally designed to be somewhat chaotic and improvisational. I will start off by explicating the design and function of my playable syllabus, which is the featured image of this chapter. From there, I will situate this particular approach within the broader debates around game-based pedagogy, in particular addressing various perspectives on the utility and appropriateness of gamified curricular approaches and mechanics to influence social learning and engagement. I will conclude by discussing data and observations that emerged from my experiments with the playable syllabus, as well as key principles of GBL that could be extracted to other curricular contexts.2

Writing with Comics Game Board, Second Edition

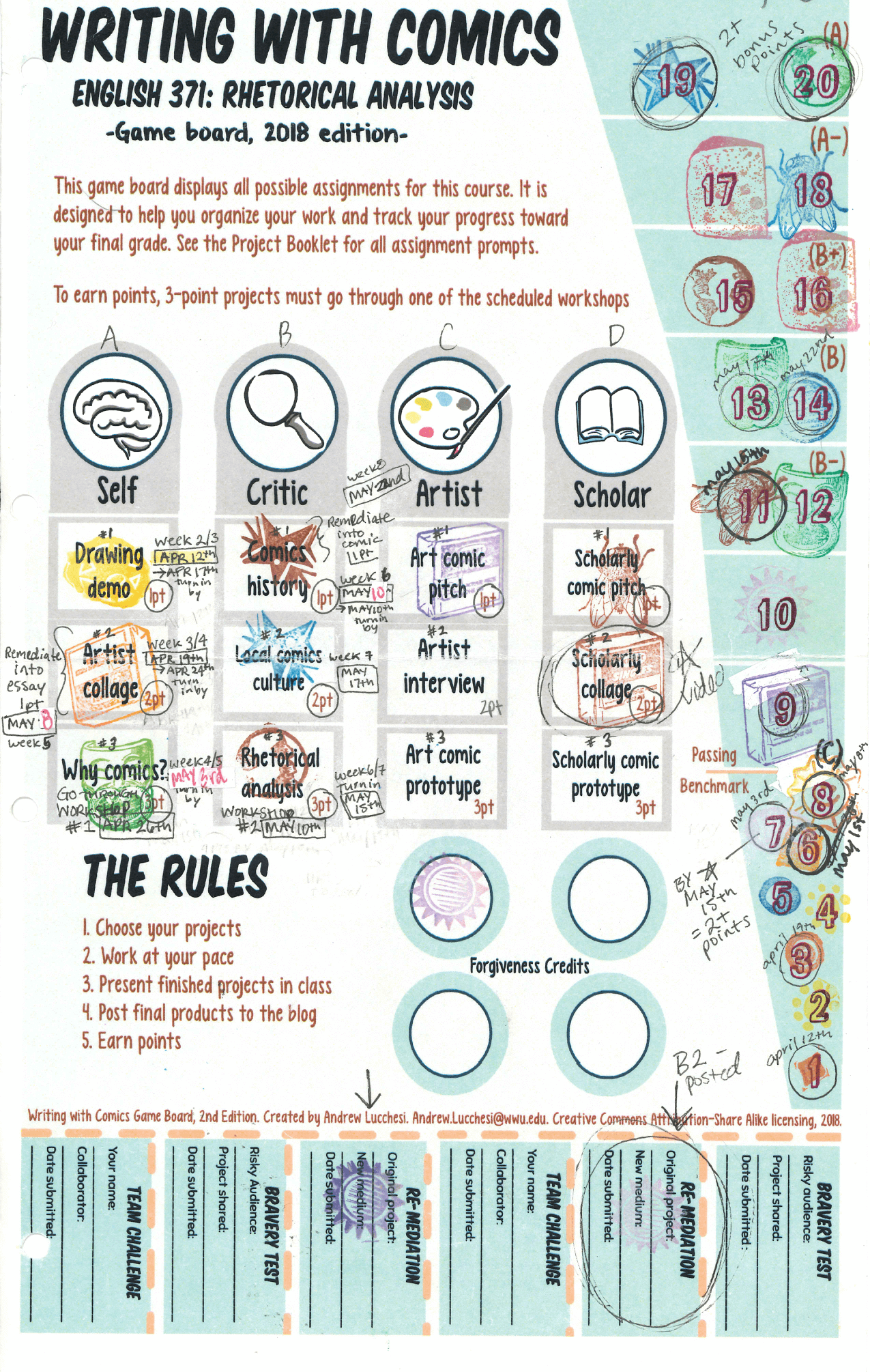

Figure 1. Playable Syllabus

My idea for the game board emerged from the course content of my junior-level writing studies seminar: Comics. I wanted to balance the course between rhetorical analysis and multimodal composition, and I wanted it to appeal to the skills of the three main populations interested in the course—writing studies students, creative writers, and visual artists. Rather than privileging one group over the other, I designed a system that would allow students to choose the kinds of work they wanted to do and then cross-teach their expertise to one another. So, since comics genres and media appeal in different ways to fans, scholars, or creators, we could effectively get the full spectrum of approaches to the subject, assuming students were empowered to take the lead.

I will draw attention to a few central visual elements from the game board and give a bit of rationale for their design. I should note that the featured image for this chapter is the second version of the game board. The original version, which was hand drawn and somewhat cruder, is included near the end of the chapter. Both versions include the same functional elements, though the layout and design aesthetic are different.

Course policies—My goal was for the game board to contain most of the course policies from the syllabus that would matter to students day to day—attendance, the grading scheme, how to choose and submit projects. However, the limited space of the page (usually printed 11x17 or legal size) forced me to boil off almost all prose from the syllabus. The second version of the game board contains only four complete sentences and one short list. All other policy concerns are represented through the playable design elements such as the “forgiveness credits” area of the game board. These represent the penalty for missing a class or a required homework assignment. The first four penalties are forgiven, but after that, students start losing points toward their final grade. The visual element reinforces and helps students keep track of the official policies that are spelled out in greater depth in the full prose syllabus.

Scope of the course—The two main areas of the game board are meant to help students visualize their decisions over the 10-week span of the class. In the center there is a group of 12 boxes, each one naming a writing project students can choose to do. They are loosely grouped into themes, and within each theme they are stacked in terms of difficulty and complexity. The projects range in value from one to three points, with the highest value projects requiring extra rounds of workshopping before they can be turned in. Students may complete any combination of these. They can learn about each one in a separate “project booklet” that gives a full prompt, rubric, and submission instructions.

On the right side is a point meter ranging from 1–20. As students submit projects, they earn points on this meter. The meter indicates how many points are needed to achieve a particular letter grade in the course. Between the point meter and the projects boxes, students are able to visualize the choices they can make with their projects and the repercussions for their final grade. Students used these tools in various ways as they moved through the course—some planning every project in advance based on a target grade, some weighing decisions as they went. I will discuss particular student experiences later in this chapter.

Playable Elements—One piece of feedback I got in focus groups following the first iteration of the course was that I should better use the material qualities of the paper itself to build more ways for students to physically interact with the game board. This focus is most evident in the design of the “old faithfuls,” extra credit projects that are available for any assignment in the course. In addition to the twelve standard assignments, students may do three kinds of extra credit projects: revising a project into a new medium, expanding a project into a collaboration with another student, or sharing a project with a professional comics artist for expert feedback. Whereas the original design listed these extension projects as triangles generally in the middle of the game board, the revised design rendered them as pull tabs at the bottom of the game board, like you might find at the bottom of a bulletin board flyer for karate lessons or a used sofa. The idea was to visually communicate the fact that these projects are consumable (each can only be done twice) but that they are available at all times. Previously students forgot about these opportunities, not realizing how many points they were worth overall. Like most elements of the design, this one was made to emphasize the choices available to students and the repercussions for making them.

Game-Based Learning Under the Spotlight

In recent years, writing curriculum designers have begun importing the principles and mechanics of games into all sorts of classroom contexts, primarily as ways to enhance and diversify the social dynamics and interaction styles available in those environments. One prominent example of such an approach taken into the professional world is C’s the Day, an augmented reality game in which attendees at the CCCC use “Quest Booklets” to complete an array of conference-related challenges (going to social events, talking to a publisher, attending a range of panels).3 Gathering enough points earns players special prizes, including collectable trading cards from the field of composition (many scholars, journals, and organizations have cards), with the highest prize being an ornately decorated toy horse pin dubbed a “sparklepony” (deWinter & Vie, 2015; Sierra & Stedman, 2012). This reward system, though not of any monetary value, essentially takes the potentially intimidating process of acclimating to a complex professional space and turns it into a kind of scavenger hunt, where trophies provide clear signals that the player is making progress. There is also something to be said for the bragging rights that come from collecting a full deck of trading cards or joining the rare stripe of CCCC goers sporting a sparklepony pin.

C’s the Day and my own curriculum represent a kind of game-based design approach known as “gamification.” As Rebekah Shultz Colby (2017) reports in her survey of GBL approaches among writing instructors, most faculty who incorporate game mechanics into their classes do so by means of stand-alone board games, card games, video games, and the like; students play these within the classroom context as the basis for lessons on any range of topics (Shultz Colby, 2017, p. 61). Gamification is a less common approach where traditional social environments like classrooms or workplaces are adapted to incorporate game mechanics. By providing tiered challenges with multiple routes to success, C's the Day adds game mechanics of strategy and competition to its players’ conference-going experience (Bisz, 2012). While the CCCC conference hall might not look very playful to most, those who have the C's the Day Quest Book tucked under their arms experience the space as augmented with the unique social mechanics of games.

A spectrum of critiques has emerged about C’s the Day’s approach to gamification as well as gamification in the classroom more generally. On one end of that spectrum, for example, Joshua Daniel-Wariya writes about gamification as a way to infuse a sense of fun into writing classes. While he values the notion of play—in the sense that writers play as they compose and set themselves challenges to conquer through their writing—he rejects the notion that flashy games are necessary to make the writing process more fun. 4 He argues, “In order to truly engage with the play of writing we have to embrace its difficulty, not gloss over it or cover it up with a gamified lexicon. Gamification masks difficulty when writers need to engage with it directly” (Daniel-Wariya, 2017, p. 317). Likewise, critics of C’s the Day argue that it too is too game-like and fun-obsessed for a serious professional space like an academic conference. As deWinter and Vie report, some saw the gamification of CCCC as potentially damaging the credibility of both our flagship academic conference and our discipline with other academics (deWinter & Vie, 2015). From this perspective, gamification doesn’t add anything valuable, but rather it reduces the value that comes from seriously confronting the difficulties of professional environments like conferences. To use mere fun to reduce the stressors of professional decorum and reputation building would be to reduce the value of the entire enterprise.

While this end of the critical spectrum infantilizes and dismisses the utility of games in serious spaces, gamification critics at the opposite end value games and play very highly. Media studies scholar and game designer Ian Bogost summarizes this critique in his widely cited blog post “Gamification Is Bullshit” (2011): “Game developers and players have critiqued gamification on the grounds that it gets games wrong, mistaking incidental properties like points and levels for primary features like interactions with behavioral complexity” (Bogost, 2011). While he observes that it is quite easy for marketers and teachers alike to import some game-related language into their projects, this has very little to do with what games are actually capable of and how they work on a mechanical, rhetorical level. So, while the first critique accuses gamification of taking serious academic situations too lightly, the latter perspective argues that games are not the problem, but shoddily conceived pseudo-games are. From either perspective, the impulse to make things game-like deludes, rather than adds to, the value of participating in the learning or professional environment. If we are to imagine gamification as more than a gimmick, we will have to show both that a game-based curriculum can produce seriously challenging learning, and that it can be a seriously good game.

Gamification, Gamefulness, and the Pursuit of Meaning

Shultz Colby (2017) offers a productive middle ground between these critiques. On the one hand, she joins in decrying simple, gimmicky gamifications, which can actually decrease the player’s motivation if the game mechanics don’t seem inherently meaningful (2017, p.67). She argues that gamification can succeed, however:

Gamification can be a powerful form of teaching, especially if the gamification design is what Jane McGonigal (2011a) terms ‘gameful’: design that poses an intrinsically motivating problem, that fosters social bonds and positive emotions, gives a sense of accomplishment, is inherently a meaningful pursuit, and positively transforms a process, a tradition, or an institution, or in an educational context, student thinking. (p. 67)Within this model, gamifications shouldn’t be judged by how serious or silly the game-play appears, but by what they have to offer the players on a personal level. The play mechanics, though essential, are something of a means to an end; what matters is how the game engages the players’ passions and desire to learn. As Bump Halbritter puts it, our play-focused assignments should “rely on the fundamental role of play because it is through play that functional knowledge is developed—knowledge necessary to help students not only accomplish critical and rhetorical ends, but reveal those ends as possibilities” (2013, p. 232). This emphasis on the goals of play is key, not only because it draws our attention away from value judgements about play styles (e.g., you are not allowed to act silly at CCCC) and toward acknowledgements of the real social, cultural, and cognitive rewards the best games are designed to impart.

In their 2015 webtext “Sparklegate: Gamification, Academic Gravitas, and the Infantilization of Play,” Jennifer deWinter and Stephanie Vie explain how they and the other scholars who designed C’s the Day had more in mind than a frivolous game with points and conference-related prizes. The game was intended to provide a practical service to graduate students or other newcomers attending CCCC who either didn’t initially understand how to make use of the complex professional environment of an academic conference or who simply had a hard time doing so on their own. As they put it, “C’s the Day quests are structured to encourage networking and participation within a framework of fun” (deWinter & Vie, 2015). Within the context of C’s the Day, even a shy first-time attendee might find the courage to approach a senior scholar and talk about their work. Indeed, the game enacts what James Paul Gee terms a “semiotic system” through which players of a game are bound together to play out particular roles and values (2003, p. 43). To return to the notion of “gamefulness,” we see that C’s the Day manifests the “inherently meaningful pursuit” of professionalization in writing studies (Shultz Colby, 2017, p. 67). Winning the game and getting a sparklepony might be the goal of C’s the Day, but becoming a more competent and confident participant in the professional world is the real point. Identity, play style, and ultimate goal all become productively wrapped up within the experience of the game.

Observations of a Game-Based Comics Course

When designing game-based curricula for writing courses, we have to balance several priorities. First, we must articulate the inherently meaningful pursuit that will propel the game. For C’s the Day, that pursuit is the desire to get the most out of CCCC and excel as a professional in the field. Second, we imagine the sorts of choices and behaviors that would help a student in that pursuit. Third, we design materials and game-play practices that will motivate players to make choices, learn new strategies, and generally play the game. Finally, as with any curricular system, we assess how the game’s components and mechanics are working for students and for the teacher and iterate these curricula into another generation.

My first priority with this curriculum design was to find a game-based system that would foster in students a unique, authentic pursuit particular to their skillset and background. One of my key hopes with the comics and rhetoric curriculum was that students—regardless of academic background—would gain a personal, intellectual, or creative relationship to the communities of comics readers, artists, and fans. This goal doesn’t attest to the full content of the course. We read challenging texts about visual rhetoric and comics history, and we completed difficult writing projects, both in printed words and drawn images. However, within the ecosystem of this game-based curriculum, students’ primary job is to find a personal identification with comics fandom; the rest of the curriculum is there to provide a challenging and structured way to do so.

To demonstrate what I mean, let me do a bit of storytelling about how the course works day to day. It usually takes at least two weeks of the quarter for students to get acclimated to the topic of the class and start to select projects from the game board. By week three, a few brave students share their first projects—often these students come in with some expertise, either with drawing or with comics knowledge. These frontrunners set a high bar for project quality, but they also set the rest of the class in motion to begin choosing projects.

As an interactive visual document, the game board provides a challenging framework for students as they make these plans. Students get to make their own decisions, but must do so within the economy delineated on the game board. Point values are weighted by the amount of complexity and difficulty involved in each project, irrespective of whether the project is about rhetorical analysis, multimodal composition, or literacy narrative. This value system allows students to follow their creative and academic interests first and foremost. However, the point scale is cued such that a student can’t reach an A grade without branching out beyond their individual specialty. So, the assignment’s point value motivates students to direct their learning in two ways, depending on how high they want to score in the class. By selecting a project that fits exclusively into their own specific interests, students can pass the course earning a C or B. These students, by sticking only to what they know best, will distinguish themselves as leaders in their specialty areas among their classmates. To excel in the course overall, however, the system requires students to pursue new interests, at least for a few lower-point projects. These excursions outside students’ initial interests often lead to fascinating collaborations and experiments that go beyond their primary disciplinary training.

My second major consideration was to find a way for the curriculum to offer valuable choices for students to choose from, so that their desire to follow their interests would also push them into challenging and meaningful work. One of my assumptions in developing this curriculum was that students from different disciplinary backgrounds would be able to use the visual labor economy embedded in the game board to differentiate their work from one another while still accomplishing equivalent workloads. Students in the course were split fairly evenly among fine arts majors, creative writers, and writing studies students. I had some expectations about how these different populations would negotiate their way through the available projects —that the fine arts students would gravitate toward the multimodal writing and collage projects, for instance. When I tallied the actual assignment choices, however, I found a good deal more subtlety in how students used their project choices to differentiate themselves.

Across the two sections of this course I have taught so far, students completed a total of 476 individual projects (70 students at an average 6.8 projects each). By identifying the project combinations that were most and least common, I was able to identify three general profiles that nearly all students could be sorted into based on their project choices: the Rhetoric type, the Artist type, and the Comics Fan type. Students in the “Rhetoric type” stand out by earning most of their points on the large-scale rhetorical analysis project, and also completing the multimodal collage project that compares two artist’s visual rhetorical stances; these students do not do projects about comics history or culture. They often have no history with comics coming in, but they learn to see them as interesting literary/rhetorical texts worth analyzing. “Artist types” earn their points by writing and drawing comic book prototypes, and they’re the only students who do the artist interview project. These students have a bit more background reading comics than Rhetoric type students, and they see the class as an opportunity to study a new kind of creative expression or to show off and refine the artistic skills they came in with: They want to leave with new drawings for their portfolio. “Comics Fan types” earn the majority of their points from 1- and 2-point projects, especially those about local comics culture and comics history. They have been reading comics a long time and perhaps already have specialized knowledge about comics culture or lore. Their motivation is often simply to geek out—to share their enthusiasm for the comics that shaped them and voraciously seek out what’s new and different in comics today.

To reiterate, I didn’t create these three profiles in advance or design the game board with them in mind. One function of the game board is to track each student’s decisions, so I can compare them in aggregate later, both to understand what projects they chose (and in what order), and to examine how students paced themselves in their work. The profiles emerged when I started identifying which projects were universally appealing from those that only a few students chose to do. Students who did these less-frequently chosen projects tended to stick together, and they only deviated to another group’s preferred projects in rare circumstances. Each profile seems to operate following its own “inherently meaningful pursuit,” and knowing this might lead me to re-design the gamification system further in the future to take more advantage of these particular motivations.

After tapping student’s personal interest in the topic and providing a range of valuable avenues for them to pursue it, my third priority was that the game-based materials would help students engage with the course overall on a meta level, and thus make conscious everyday decisions about their work that would add up to a unique final portfolio. Students made their choices and pursued their goals within the visual rhetorical framework of the game board and other curricular materials. When I interviewed students about the game board and how they worked with it, they repeatedly described it through metaphors of time and space. One student described the playable syllabus game board this way: “It’s kind of like a schedule, but a not-filled-out schedule. A calendar without any dates written in yet.” Many students, in this vein, described using the game board as a tool to plan future projects—some even going so far as to write in personal due dates for each project they intended to do, scheduling themselves from the first day of class to the last. Another set of students did not describe the visual syllabus in terms of time, but instead used metaphors of space: a map, a restaurant menu, a landscape. One student explained, “It’s kind of like how my brain works. I like to map things out.” Within this metaphor, the “space,” what’s being mapped is the course material itself, the particular project options.

Naturally, these metaphors of space and time are connected. What is especially compelling about this set of metaphors is the way it speaks to issues of genre and medium activated whenever we design curricular materials, especially syllabi. Within a traditional syllabus, the content of the document is laid out linearly, from the top of the first page to the end of the last page—students experience it slowly over the course of the few minutes it takes them to read the syllabus front to back (if indeed they ever read the syllabus). This is the static picture of the class as content to be covered—as landscape to be traversed. Syllabi often end with a daily schedule for the class, indicating what bits of content or assignments will happen when. This is the map of that landscape—the steps involved in traversing it, and about how long each of those steps should take.

Visual rhetorical texts have unique affordances when it comes to representing space and time. Comics theorist Scott McCloud explores this idea when describing how comics artists portray the passage of time in a static pictorial medium (McCloud, 1994). Fundamentally, how long a bit of action in a comic appears to take (say, from Superman taking off in one panel and landing in another) comes down to frame size, image sequencing, perspective, use of white space, and other nonverbal signifiers that do not, in themselves, have anything to do with the passage of time. Comics readers learn, through experience, to interpret the visual cues to fit within their everyday experience of time passing.

As students learn to use the game board, they must learn—just like comics readers—to view a static visual text and interpret something happening across time. It is not like a student can use the game board to help manage their daily work time without also making selective choices about what course material to prioritize; nor could they decide which projects to cover without also considering how the projects will affect their workload across the span of the term. In this way, a playable syllabus allows students to approach the problem of reaching their point goal from either conceptual angle, and to oscillate between spatial and temporal thinking as the course plays out. So, whether students primarily experience a playable syllabus as a calendar without dates or a map of abstract terrain, they’re working to envision the course as a whole and actively construct their engagement with it. This is more than we can assume, I think, when we hand them only a traditional four- or five-page syllabus in 12-point font.

The Limits and Possibilities

By way of a conclusion, I would like to offer some considerations for using game-based curricular approaches in other contexts. It is rare that I get to teach this upper-division themed course, which gives me a great deal of time to tailor-make a gamified curriculum and revise my materials.

I do not suggest that the playable syllabus game board I present here will work in all circumstances. In my current role as director of composition at a regional state university, I design curriculum for our first-year writing course, English 101, which offers 80 sections each year, taught entirely by myself, my assistant director, and 30 English MA/MFA students whom I train and supervise. The gamification strategies I use with my comics course would be a risky fit in English 101. At least initially, first year students tend to have a difficult time tapping into an authentic internal motivation in a required first-year writing class setting. Even taught by an experienced instructor who understands the mechanics of the course, it can take more time than we can afford in our 10-week quarters in order to get everyone playing along and getting the full pedagogical value of the gamification. And since fully half of the teaching staff arrive immediately out of a BA program with no teaching experience, I have to be very careful about introducing curricular elements that carry with them any kind of ambiguity or random chance into the course structure.

With all of that said, acknowledging that one specific model of gamification won’t work for all contexts, I wish to offer a few ideas and considerations for those interested in developing game-based curricular materials. No matter where you begin, what matters most is that the visual and interactive modalities take the lead in representing how the course works for students. While I might drop a thousand words quite easily in a traditional syllabus laying out policies and learning outcomes, I focus my game board entirely on the decisions that students will make as part of their learning in the course. This is not meant to be a replacement for the traditional syllabus. Rather, as my students attest, it provides a daily reference for the class from a bird’s-eye view, so students can clearly observe their own progress and set their strategy for what comes next. Visual modalities and interactive materials offer students and instructors unique affordances to this kind of abstracted, system-level thinking.

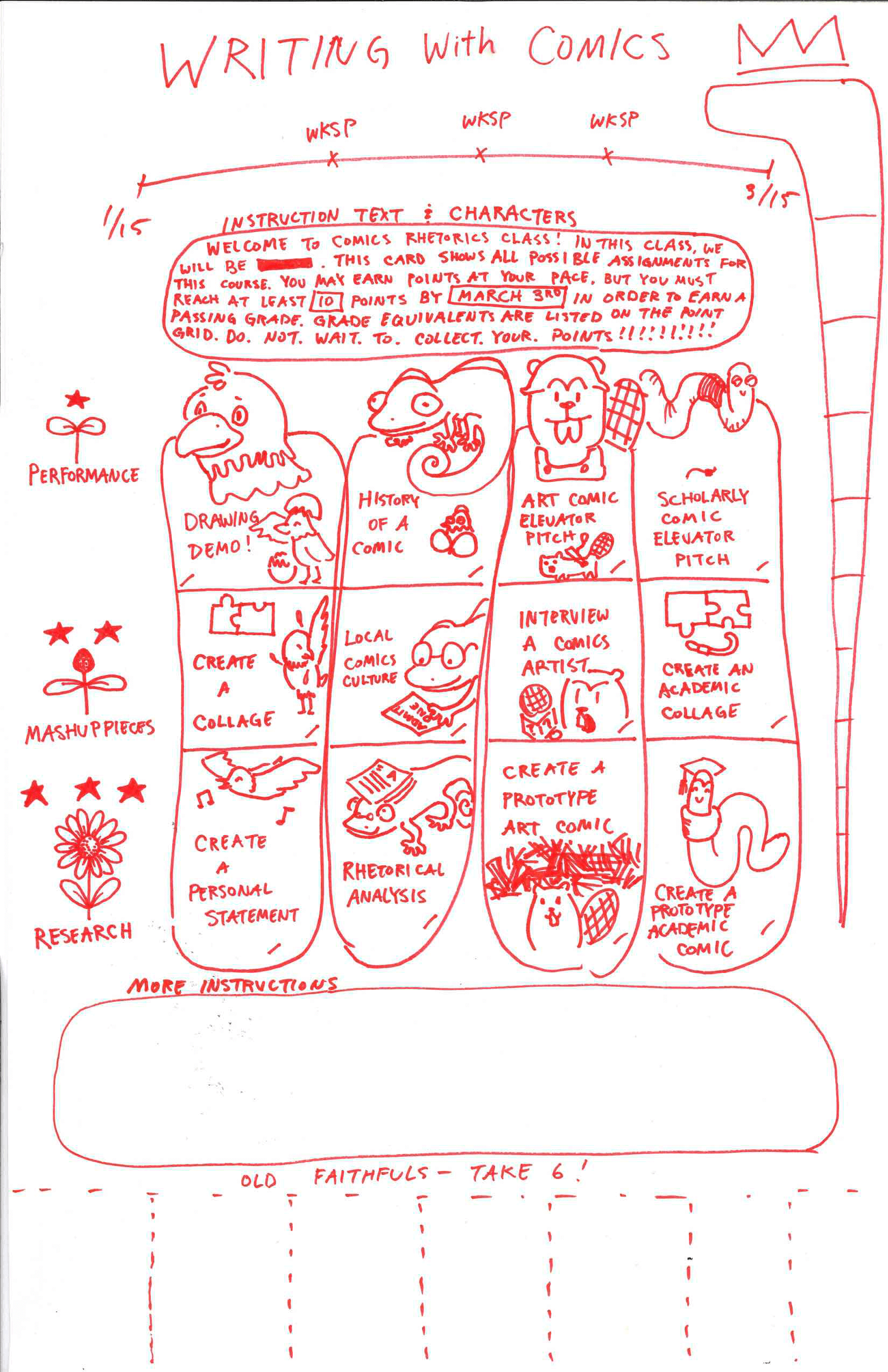

While it can certainly help to be able to hire a graphic designer to create visually exciting materials, this isn’t necessary. As you can see in Figures 1 and 2, my first attempts were hand-drawn and crude, and I relied on feedback from my first class of students to develop a more structured and visually balanced model. I am not particularly talented at drawing, but it felt important to me that I create the first version of the game board by hand, since, after all, I would be asking my students to take risks with a new medium too. The hand-drawn, open design in Figure 1 left a great deal of white space for students to use in doodling, taking notes, and writing plans. I redesigned the game board using a few simple visual design tools. Initially, I used Prezi, the online presentation-building tool, in order to shape the layout and compose text within the visual plane of the design. I later moved to Google Draw, a program in the Google Drive suite that has highly simplified versions of the kinds of tools available in a professional visual editing tool like Photoshop. I picked these programs entirely because I already knew how to make quick, readable designs in them, and because they would be easily shareable with just a link, rather than keeping track of particular file types. Much like when I was drawing by hand, Prezi and Google Draw gave me only limited options to work with. This helped me tremendously to focus my attention on the mechanics of the design—how I wanted it to be used—rather than on how I wanted it to look aesthetically. The aesthetic, I decided, could develop for future versions of the course, and my more artistically minded students have been very keen to pitch in.

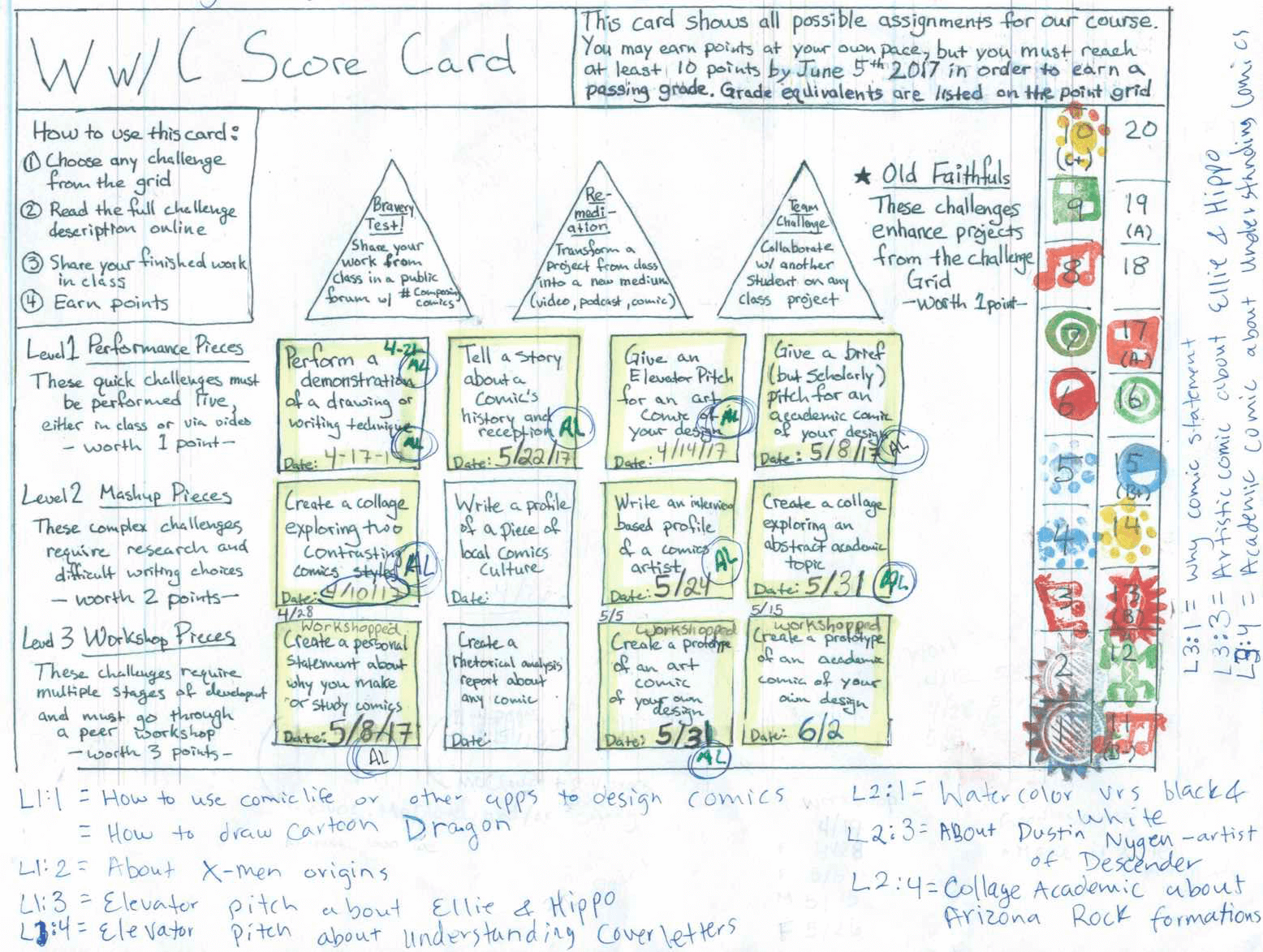

Figure 2. Playable Syllabus used in first iteration, Spring 2017. This version of the game board was drawn by me. In this image, a student has taken extensive notes on and around it.

Figure 3. Prototype of revised playable syllabus game board. This prototype was hand-drawn by Hanae Livingston during a focus group to redesign the document following the first iteration of the class. Reproduced with the artist’s permission.

I close with three considerations for those seeking to remix their curriculum to include game-based elements in general and visual-interactive materials in particular:

- Purposefulness: Game-based curricula must originate from the course’s core objectives for student growth, rather than from considerations of game play mechanics or style. It may be best to even ignore the course content initially. For instance, in a sophomore-level British literature course, it might not matter for the purpose of the gamification exactly what periods of literature the class covers; rather, consider the intellectual habits and scholarly practices that will help students improve as British literature students. Maybe this includes challenges about the history of British popular culture or close reading in different contexts. By starting with student learning goals, you have a much better chance that the gamification and game-based materials provide a real enhancement to the students’ personal investment in the class and their decisions within it. Designing for gamification requires us to be attentive to the ways we prepare for student decision-making. WPAs might look to the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” (2011) as a possible guide in this way of thinking in that its focus on habits of mind and cognitive processes pushes us to be choice-oriented in designing curriculum, rather than strictly outcome oriented. To pursue GBL is to seek out ways to foster playfulness as a habit of learning, while designing courses in the mold of the Framework naturally pursues many habits of mind charlatanistic of any experienced game-based learner, including openness, engagement, persistence, and flexibility (pp. 8–9).

- Stability: Perhaps this goes without saying, but game-based curricular materials must be carefully designed and internally coherent. I know from experience that the visual design of curricular documents takes particular care. This is not because visual rhetorical course documents need to be professionally rendered, necessarily, but because the visual-spatial rhetoric features of the document must be intuitive, unambiguous, and yet flexible enough for player customization. Commercial games are rigorously user tested to ensure that the instructions are extremely clear and that game play is smooth and consistent from session to session. If this attention to detail is important in a board game that lasts thirty minutes, it is much more so in a gamified class that lasts the length of an entire term, where a poorly devised points system could cause all sorts of stress and confusion. It is for this reason you might consider gamifying a single unit of a course, or even a single week, at least at first. Simulation-style games, role-play scenarios, and augmented reality games like those described by J. James Bono can work well on these timescales (2008). To work out the kinks in new gamifications, consider running some simulations with your faculty and volunteer students. You can gain much from applying GBL practices to course development activities like this. Perhaps you assign yourselves roles as students with different skills and motivations for engaging or disengaging. Not only can this help make sure your gamification is well cued to student’s internal motivations for engagement (as best you can guess them before actually running the game for the first time), this can also help to identify where there is any room for ambiguity in the instructions or materials that could turn into a big problem later. Further, by bringing this element of role-play into the course-testing process, you have the chance of moving beyond simply telling whether the new course documents work or not. Rather, you can use your own ethos of productive play as a group of instructors to help you develop a more playful course design.

- Autonomy: In thinking about handing over a game-based curriculum to the graduate student instructors who teach my program’s English 101 courses, I am aware of how daunting and confusing such a system would be to a first-time teacher who has never taken a game-based course themselves. This is true for all WPAs who introduce new curriculum to their programs, of course. Game-based curriculum, because of its focus on game mechanics and playable materials, can put new instructors off kilter. You have to trust the game to be well calibrated, and you have to believe the play style will benefit the work of the class. For experienced instructors, giving this kind of power over to a gamified system (or any new curricular innovation) may seem threatening to their authority. For novice instructors, who may not have much authority in the classroom to begin with, the randomness and uncertainty inherent in games may seem completely overwhelming. In order for a gamified curriculum to be scalable to multiple classrooms and instructors, it must provide an easy entry point for both the instructor and the student, onboarding them to the game experience as the course progresses. Game-based learning scholar Joseph Bisz suggests that when the game mechanics are properly in place, the instructor is free to take on more of a “coach” role, helping students make meaningful short-term decisions within the long-term context of the gamified curriculum (2012). As much as possible, the game should be designed to acclimate the instructor to their role, whether it be rule coach, umpire, or cheerleader.

The principles of GBL have a great deal to offer WPAs even if they do not go on to design multicolored game boards to replace their program’s syllabi. At its heart, GBL is about modifying the rules of the class to carve out new ways for students to use their imaginations, collaborate, and make decisions than they would in a more traditional structure. We design such curriculum because we believe that this choicefulness matters—that it allows students to be themselves in a way that is otherwise stifled by standard academic curriculum. I can see the same kind of motivation behind the grading contract movement: a desire to strip away the oppressive rules of the academic game (bad writing = bad grades) to allow students to be themselves, work as they see fit, and not be held to the role ordained by the dominant language traditions. In either case, the approach to curricular design, if taken to the programmatic level, is remarkably similar: create a document that will set to the side whatever course mechanics get in the way of full, embodied engagement in the work of learning. Not everyone will be drawn to the artifice of games, but most any curriculum designer would want this kind of engagement for the courses in their program.

Even as I acknowledge the challenges of designing a successful, scalable gamified course, I cannot help but see the possibilities. Just as in my comics course, English 101 students arrive from a range of disciplinary interests. At its core, the mission of our English 101 is to help students develop writerly habits and identities they will be able to carry with them as they become experts in those disciplines. I aspire to design a semiotic system where students are motivated to game their way through the course, finding adaptive ways to achieve the course’s extrinsic aims while following their intrinsic interests and ambitions. However, in most instances, students see the course as a series of imposed tasks and hurdles—extrinsic motivators to be followed with some resistance.

Separate from any bigger questions about curriculum design for a first-year writing class (assignment types, learning outcomes, etc.), could we make curricular materials that would help students approach a course like English 101 as if it were a playground? What kind of visual, interactive course documents could help foster that playful engagement? What kinds of rule books could brand-new teachers of these courses use to call the balls and strikes as students engage in this play? These questions, as of now, still lead to unmapped territory.

Notes

1. See an updated and interactive explanation of McCloud’s “Big Triangle” at http://scottmccloud.com/4-inventions/triangle/index.html .↩

2. This project emerges from an IRB approved study that included interviews, focus groups, and quantitative analysis of seventy five game boards.↩

3. See the 2015 C’s the Day materials at http://cstheday.org/ .↩

4. Daniel-Wariya draws a useful distinction between play and games: “While the terms game and play often seem synonymous, they are not the same. While games can be described as a context of rules, space, people, materials, and valorized outcomes, play is an activity or way of moving in that context” (2017, p.316). ↩