04. WPA Responsive Genre Change

Using Holographic Thinking to Unflatten a Celebration of Student Writing

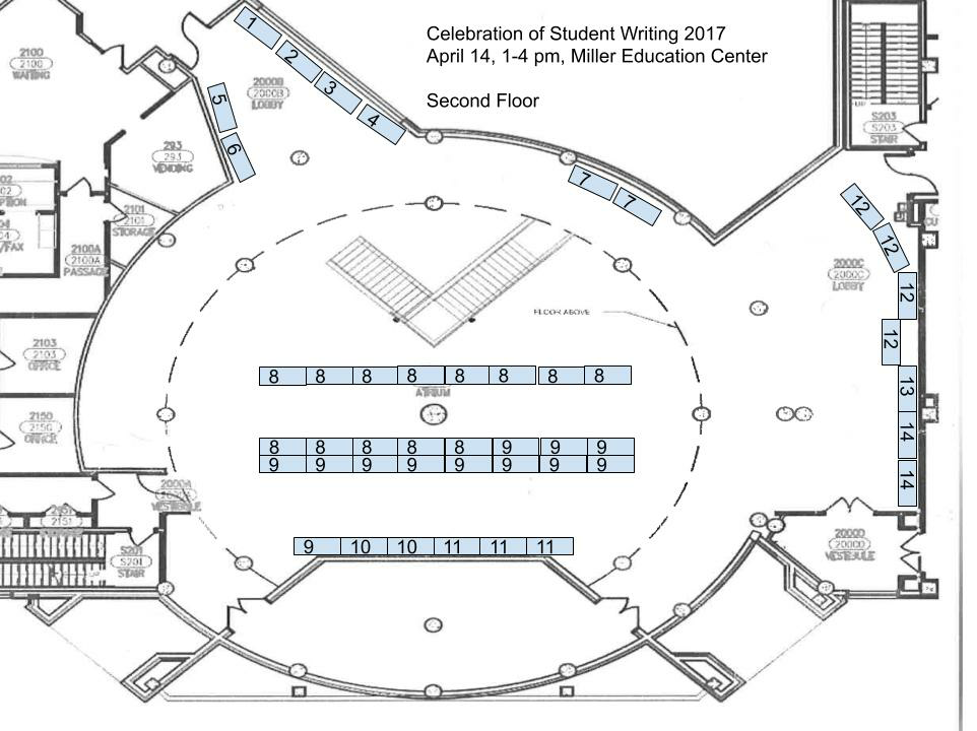

Last year’s Celebration of Student Writing ended like all of the CSW events we have attended: some students lingered, still talking to each other about their research, audience members slowly filtered out, faculty shared compliments and critiques with each other, and we, the WPA and graduate student jWPA organizers, breathed a sigh of relief. The soundtrack for these final thoughts was the shuffling of paper beneath our feet, the leftover confetti of CSW maps we had printed in color to ensure that they were easy to read. That physical artifact (Figure 1) had been the confluence of a year’s worth of planning. All of the emails, phone calls, meetings, and last minute shuffling was aggregate in the final map. The genre had mediated relationships between all CSW stakeholders—the students, the instructors, the WPA organizers, and the setup crew. However, as demonstrated by the nearly intact pile of leftover print maps and the few scattered underfoot, it was clear that most CSW participants did not have the same reverence for the maps as we did.

Figure 1. The Middle Tennessee State University 2017 Celebration of Student Writing Map, Permeated by Flatness

When we looked at the map, the CSW came to life with a sort of attendant holographic magic. But for other stakeholders, the genre was not necessary or representative of their CSW needs: it was flat. By looking at genre uptake at the CSW, and particularly how this iteration of the map functions as an occluded genre, one that is only useful to its organizers, we better understand how the CSW means to different stakeholders. John Swales (1996) first identified occluded genres as genres within academic discourse that, though essential to publication and scholarly advancement, are invisible to apprentice researchers. By drawing attention to such genres, Swales invited faculty, and particularly graduate student mentors, to talk explicitly about essential processes that lay outside the visual field of apprentice discourse community members. Here we adapt the term to the WPA context with a critical bent. Explicit education that provides access to occluded genres in the graduate writing sphere allows fluid movement within established hierarchies. In WPA work and classroom contexts, however, the recognition of occluded genres that only have meaning to the WPA or faculty member and her immediate colleagues reinforce the inequity of decision-making and representation that is the hallmark of many such contexts.

Faculty are often familiar with the realization that a particular genre is valuable to them but not necessarily their students. For instance, faculty often lament, “students never read the syllabus!” Instead of reading this lack of uptake—this demonstration that a syllabus often functions as an occluded genre within the classroom—as a fault within our students, how might we instead consider such evidence as a signal to change tack, to consider who is served by and who is excluded from a given genre? Most importantly for us, how can consideration of occluded genres function as an activation point for reflective, institutional critique? In the following we answer this latter question, considering why our original map (Figure 1) did not effectively represent program stakeholders such that they might see the artifact as useful for our CSW. We trace reflective genre change in our program, identifying how progressive revisions of our map make tangible the evolution in our theorizing more expansive access and representation within our writing program. None of the visuals we provide are perfect, but we offer them as a sort of multimodal heuristic. Instead of offering a recommendation of the “right” genre for other WPAs and their attendant CSWs, we offer these artifacts as footholds that trace our attempts at addressing programmatic change and as a potential path for colleagues. As WPAs we need to develop opportunities that invite what we are calling holographic thinking across program stakeholders, the ability to animate WPA visual genres and make them meaningful. We suggest that composing visual genres, such as maps, can be one of these opportunities. Ultimately we advocate this process of WPA responsive genre change, suggesting that it might more equitably distribute decision-making within a program and make central visual genres as productive tools for programmatic revision and institutional critique.

Local Topography: Our Celebration of Student Writing

Celebrations of Student Writing, though not entirely ubiquitous across writing programs, have been a hallmark of writing research courses for years. Linda Adler-Kassner and Heidi Estrem (2003) first wrote about Eastern Michigan University’s embrace of the CSW as the writing program’s capstone experience in 2003. For them, the CSW was “intended to assert a more public presence for college writing” and “address the struggles some writing instructors describe in their discussions of research writing.” Further, in redesigning their curriculum they were eager to find a balance between instructor autonomy and program coherence; in short, they “wanted everyone to be in the same ballpark, even one as big as Yankee Stadium” (Adler-Kassner & Estrem, 2003). The CSW allowed this program coherence to develop organically, to orient questions about curriculum design in terms of a clear, tangible context, “a rhetorically situated audience” (Carter & Gallegos, 2017, p. 79). One of my colleagues, Chelsea Lonsdale, describes the CSW as a sort of “science fair for writing,” an apt description, though in some ways a CSW is the anti-science fair, a demonstration that humanities research need not be defined in terms of the scientific method.

Instituted in 2016, our university CSW is, in many ways, still in its fledgling phase. Although many CSWs are particularly dedicated to displaying the fruits of research writing developed in the second semester composition class, at our university all English classes are invited to participate. First-year students through graduate students are represented in our event, as well as students taking composition, literature, and creative writing courses, and we offer simultaneously the fair-style art installations and poster presentations in one room during the CSW, and creative readings and plays in an adjacent space. In this way our CSW has a departmental mission of uniting English sub-disciplines that is perhaps a higher priority for us than demonstrating the products of research writing to the wider university audience. Because of this our map has a complex goal: to preview the reality of the event such that faculty and students who might be unsure about participating—given contingency status, discomfort with public presentation, or traditional expectations of the products developed in an English class—are reassured.

Our event takes place in a recently renovated former hospital, what Marc Augé (2009) calls a non-place, those hallmarks of supermodernity that are “formed in relation to certain ends” with no tether to the past of the space they occupy, blank functionary locations pre-made to be filled and made meaningful only by virtue of the behaviors they facilitate” (p. 76). The main room is composed of two floors of an airy atrium, which allows the presenters to look up and down at each other during the event. Participants tend to, like moths, cluster toward the windows during the event. Like Adler-Kassner and Estrem’s event (2003), ours is “loud with the sounds of people talking with writers, about writing, not about writers (without writing)” (p. 128).

Our 2017 CSW map (Figure 1) is a remixed, repurposed architectural diagram that uses the flattening of this non-place, hospital-turned-university building to situate this creative, energetic event. The map offers a view of the space were we to examine the second floor through the roof itself. This disembodied view further distances readers from the holographic experience of the CSW that we wish to communicate in advance of the event. We hope that the map will get students and faculty excited, that by holding the map they will see what we see in the organizing process. Instead, they see numbered rectangles, which delineate tables, gently hemmed in by circles meant to represent columns. One can look at the map without seeing an indication of people whatsoever—just a set of predefined choices: boxes, lines, legends. These predefined choices echo from the map’s composers to its users: students, teachers, and other participants look at the map and it scripts their response to the event. Readers don’t just look at the map to see where they need to be; the map tells them that there is a box within the space that is theirs, and, once they locate their “territory” in physical space, the map is no longer necessary.

Though the participation of students is unquestionably the heart of the event—after all, it is the Celebration of Student Writing—their participation is flattened out of existence in the two-dimensional map. Lost, too, are the countless instructors who bring their classes aboard, not to mention the many hours of labor both they and their students invest in preparation for the event. In light of this, it is no wonder that uptake of the genre is so limited; the flattening of roles this map enacts effectively reduces participation to two camps: the organizers and the organized, WPAs and everyone else. Only the organizers—the WPAs—are privy to the ways these roles intersect, the places where these disparate avenues of participation meet each other and create the visible whole.

Unflattening Our Map/Inviting Holographic Thinking

To understand why our map functioned as an occluded genre for our CSW participants, we are informed by Nick Sousanis’ (2015) theory of “unflattening.” Drawing from Edwin A. Abbott’s novella Flatland, Sousanis explores how “flatness” can limit and dictate the knowledge that the two-dimensional produces. Sousanis explains the nature of flatness by examining a penny on a table from different perspectives. Depending on the viewer’s relationship to the penny, it changes—it may be a circle when viewed from above; an ova, when viewed from a 45 degree angle; or a line when viewed directly from the side. If one approaches the penny from the side and only sees a line, they do not consider whether there is “more than meets the eye,” or whether this line takes a different shape from above. Anything viewed for what it is as it is presented (or positioned) has had its landscape “permeat[ed]” by flatness (pgs. 7–8), it lacks rhetoricity. Sousanis suggests that flatness is not due to the nature of the second dimension as much as it is to our innate nature, which “starts early” (p. 10) to “box [us] into bubbles of our own making…row upon row…upon row. Thought and behavior aligned in a single dimension” (p. 16). To do this, we utilize the second dimension; we choose lines to box, separate, surround, (de)limit, trace, or end various representations of space. With these representations often come labels identifying those spaces or assigning people or things to them. As a result, flatness can lead to a focus on the “predefined choices” of a space, and a “forget[ing] of the wonder of what might be” (p. 9).

To combat this tendency to “forget the wonder of what might be,” we turn to a central concept in holography: hogels, which function as an antidote to the arhetorical flattening that our paper map constructs. In 3D imaging, hogel is the term for an image’s constituent elements, the holographic equivalent of the pixels that collectively constitute a standard two-dimensional image. In a hologram, light that interacts with these hogels takes on not just color but positionality within the broader image, a three-dimensional relationship with all the other hogels. A hogel in the beak of a holographic bluebird is not just yellow, but yellow and high in the front of the image; the hogels in its body are blue, but have individual locations on the wing, on the tail, perhaps even arranged to give the shape of a feather. Embedded in every hogel is information about how that constituent is related to, and therefore helps constitute, the broader image. Awareness of hogels is effectively the opposite rhetorical move of the metonymic representation exemplified in our map, in which the parts—boxes, lines, and legend—must represent the whole.

For our purposes, holographic thinking requires not just attending to the picture, program, or event as a whole, but also paying closer attention to individual hogels, the constituent elements of the CSW, because they are the fundamental elements with which that broader vision is created. Functionally this means that instead of doubling down on an occluded genre—insisting that students consume syllabi, for instance, by giving quizzes or reading them out loud in class—as WPAs we facilitate purposeful genre change to more effectively select genres that meet programmatic needs. By minding our hogels more carefully, and taking as meaningful the trampled pile of maps leftover at our CSW, we set out to unflatten our map of the event by adding some of the depth and volume that each individual participant contributes, thereby selecting genres that give credence to the textured reality of the CSW. We also address the limitations of each iteration, hoping that our revisions might be instructive for other WPAs who hope to unflatten their programmatic genres.

Locating the Hogels/Revising Our Map

In what follows we offer three map revisions: Figure 2, which represents our initial attempt to apply the holographic thinking we theorize to a map of our CSW; Figure 3, the revised two-dimensional map that we circulated to participants at our most recent CSW; and Figure 4, a three-dimensional diorama that operationalizes our holographic thinking, provides opportunities for self-representation of stakeholders, and attempts at WPA responsive genre change. We also shared this diorama at our recent CSW and asked participants to “people” the model with their own likenesses.

Figure 2. Our "Holomap"

Figure 2 takes advantage of digital tools to help us theorize a map that more effectively captures the lively assemblage of planners, participants, and other stakeholders. We created a basic Wix site and overlaid the original two-dimensional image with a web of hogels, images of CSW participants who help us “rediscover the wonder of what may be,” rather than simply being boxed in to our “predefined choices.” In this map we try to focus less on location and more on “locatability,” as theorized by Tarez Graban (2013). The images we offer overlay and erase parts of our map, disrupting the orderly flatness of our original. Although Graban’s interest is explicitly archival, her metadata mapping method offers a way to locate individual actors—for our purposes - hogels—in a constantly moving space, tracing locatability, and thus, dynamic action, rather than flattening experiences. Graban “highlight[s] the networks of activity that can be visualized between their origins, influences, and actual or imagined reach” (p. 173). So too, then, does our revised map become a site of locatability rather than location, as it constantly moves and morphs with each new consideration of who is a stakeholder and what and how that stakeholder has contributed. As a map, Figure 2 does not necessarily serve its original purpose. Students and faculty won’t be able to locate their spaces on the map, but it addresses our interest in adding layers to unflatten the artifact. Given that the map relies on digital images and a user’s impulse to click without clear instructions, difficulties with usability and accessibility encouraged us to keep iterating. It’s not a perfect map, nor is it a perfect picture of student writing, but it usefully communicates our understanding of the writing that animates our Celebration of Student Writing: a heterogenous mixture of effort, enthusiasm, and achievement like you see in any one classroom.

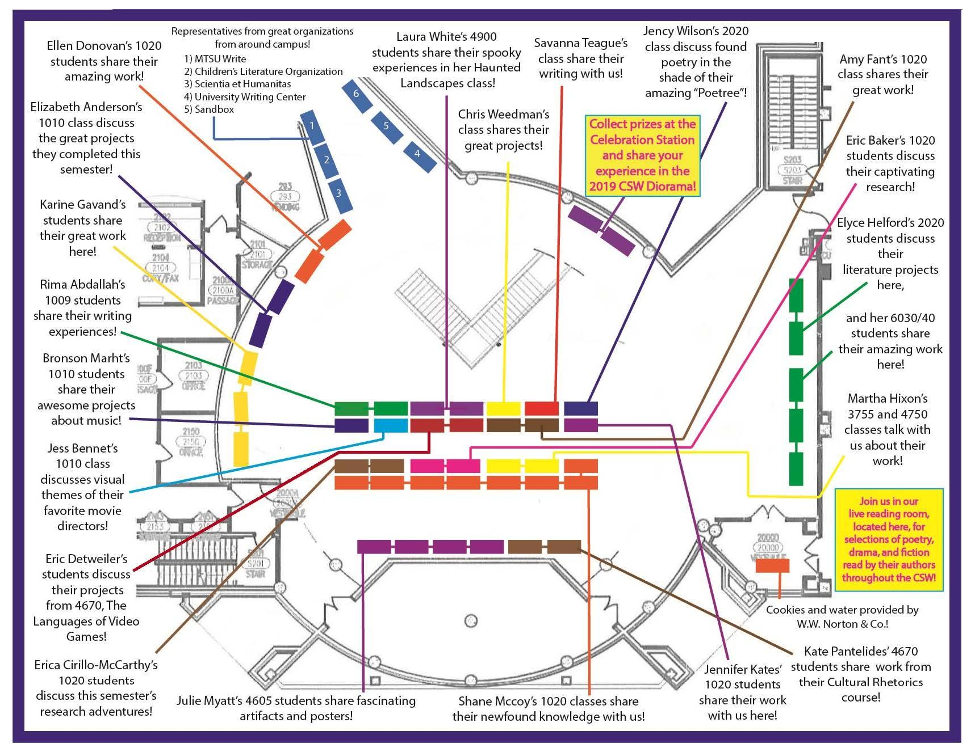

Yet this heterogeneity is precisely what we aimed to emphasize, and is therefore a hallmark of Figures 3 and 4, our subsequent attempts to unflatten our map. Figure 3, the revised 2D map we distributed to participants and posted around the event space, actively embraces the heterogeneity of our CSW community by highlighting the distinctness of its constituent parts.

Figure 3. The Revised 2D Map for the Middle Tennessee State University 2019 Celebration of Student Writing

Instructors, instead of being flattened to a simple last name, are now directly identified by name and given a unique color to distinguish themselves from one another. Students, who previously found themselves flattened off the map entirely, are now explicitly referenced in the annotation for each class, as in “Dr. Myatt’s students share fascinating artifacts and posters!” The revised map earned praise from both faculty and students. The positive response to our new 2D map meant that our analysis of the original map was correct: previous participants very well might have looked at our earlier maps and wondered “Where are we?”

Despite this improvement, however, we knew that our new 2D map still only achieved part of our goal to invite representation by participants themselves. In Figure 3 students now find themselves acknowledged, but it is only in the collective sense, as faceless groups attached to courses and instructors in the brief annotations. The map is still focused on the WPA’s need to know where to place people in the non-place. Although the genre affords easy replication and dissemination, it limits representation. It must flatten, and homogenization is a primary vector of its flattening force. Figure 4 shows our effort to address this: a collaborative diorama of the event space co-constructed with participants and attendees as the CSW took place. Fashioned from plywood and plexiglass, the diorama is a scaled down model of the event space. To populate it, we provided three primary methods: tiny wooden people figurines made with a laser cutter at our university Makerspace, simple card-stock comment cards color-coded by participant group, and miniature poster-boards fashioned from index cards.

Figure 4. The Collaboratively Constructed Diorama at the Middle Tennessee State University 2019 Celebration of Student Writing

With the development of our collaborative diorama, we hoped to give attendees and participants a way to represent their individual experiences of the CSW, to respect the heterogeneity so vital to the event by inviting personal contributions and perspectives of all the individual hogels that make our bigger picture. To our delight, the diorama table (or “Celebration Station,” as we dubbed it) was bustling with activity and enthusiasm the entire event, often with a short line of participants waiting patiently to contribute. Through its collaborative, co-constructed nature the diorama gave everyone at the CSW a chance to unflatten themselves. Sixty people made personalized wooden avatars of themselves, many impressively detailed. By a wide margin, the avatars were the most popular option for participating, which we find telling. Participants of all kinds were eager for an opportunity to distinguish themselves from the collective they had been thrust into, and the figurines gave them a chance to, in a sense, speak for themselves. Of the 60 avatars, 11 were specifically identified, either with names, initials, or affiliations. Two avatars had notes attached to them to allow these representations to further “speak” for the participants. In addition, participants created 44 cards that offered responses to the event. These cards were color-coded by type of participant: 27 red cards, representing student presenters; 8 green cards, representing associated faculty; 7 blue cards, representing audience members; and 2 yellow cards, representing volunteers. We were particularly interested in the cards contributed by audience members because this is not a stakeholder group we had previously considered as eager to have a voice in the event. One audience member noted, “It was great hearing my sister read her work!” And yet another commented: “This was an awesome experience. Made a superhero to watch over the other students.” Ultimately we found that one artifact could not meet the multiple needs for our CSW that we identified as necessary for our program, but each subsequent visual representation of our event, particularly the diorama, offered new opportunities for revision and useful reflection.

Conclusion: Building Out Our Map

We analyze these maps with James Porter et al. (2000) on our shoulders, for the ways his work encourages us to use “spatial critique as an analytic tool for changing institutions” (p. 632). Porter et. al. theorize institutional critique as a way of viewing “institutions as rhetorical designs—mapping the conflicted frameworks in these heterogeneous and contested spaces, articulating the hidden and seemingly silent voices of those marginalized by the powerful, and observing how power operates within institutional space—in order to expose and interrogate possibilities for institutional change through the practice of rhetoric” (p. 631). Similarly, we used the opportunity to consider how occluded genres function within our program, tracing lack of uptake to learn powerful lessons about stakeholder representation. Such lessons have the potential (if we let them) to help us craft programs that are more inclusive of student experiences and “the local and interdisciplinary expertise that faculty may bring with them to teaching” (Mendenhall, 2019, p. 141). Our radiant figures—and also the not-so-radiant, in the case of our initial map—structure our roles as WPAs, help us do our work, and, simultaneously, do work in our programmatic worlds.

One of the primary challenges we face as WPAs is fairly representing (and actively listening to) the individuals that our institutional genres depict. Flatness is not inherently bad, it is a necessity in developing textual and visual genres that account for our programmatic work. However, holographic thinking allows us to potentially see gaps in the stories our visuals tell. Further, we must remain mindful that metonymy acts by exclusion, because one part is made to stand in for and represent others. This convention can be dangerous if left unchecked, as it carries the risk—as it did in our initial CSW maps—of leaving vital parts of our writing community completely unrepresented. Perhaps the most significant impact of this deep dive into our administrative mapmaking is not the documents we produced but the reflective opportunities it afforded us as an administrative team.

When we first embarked on this project, our aim was to create a map that communicated the reality of the CSW more clearly. Though we hoped to deepen the message it conveyed, to us the map was still primarily a conduit for information. As is so easy to do when, as WPAs, our overarching goal is simply getting one more in a slew of complex, exhausting tasks accomplished, we remained stuck in a modal, arhetorical conception of this document. In these early formulations the flow of information remained one-directional and audienceless: from us, the WPAs who (we thought) knew almost everything about the CSW to everyone else, the many folks who needed to be informed. That constraining binary—and what are binaries but the flattening of complex realities into two-dimensional constructions—persisted: organizers and organized. Thus, we failed to recognize and attend to our genre, its multidimensional purpose, and its multidimensional audience.

We learned that to effectively “unflatten” our map, to recapture the “wonder of what might be,” we had to alter our training to read (and subsequently develop) maps holographically. We must read the way “[a] dog reads everything it encounters as a time capsule unfolding with rich layers of sensory information to discern who’s been here, what touched this [and] how long ago” (Sousanis, 2015, p. 40). Such reading allows our map to take form as something that rises above the page, liberated from the two-dimensional plane that is the tyrannical 8.5 x 11 inch flat white box. Instead, it manifests as a more “laterally branching, rhizomatic structure, where each node is connected to any other” that is truer to the polyvalent reality of what we are trying to capture and convey (p. 39).

This process of WPA responsive genre change highlights the need 1) to require genre awareness of ourselves as WPAs in all our administrative composing, 2) to select genres that invite self-representation by programmatic stakeholders, and 3) to be attentive to the changing needs of our programs and practice strategic genre change that meets those needs. Our interactive map and diorama challenge the prescriptive, modal nature of the original CSW map by not only considering the audience and the possibilities of that audience, but in fact constituting these artifacts through participation. Through such efforts to evaluate, rethink, and reinvent the genres of our administrative work, as we have done in our revised maps and diorama, we not only practice what we teach, harnessing our genre awareness to address dynamic situations, but also model the innovative genre work our program emphasizes for our entire community of writers. By unflattening institutional terrain that has become so familiar to us that it just appears as simple, flat lines, holographic thinking allows us to resee our administrative realities with a greater appreciation for their shape, complexity, and nuance.